Leah Clare Michaels is a Baltimore native, artist, activist, historian, and surfer. She earned her M.F.A. in Intermedia and Digital Arts from UMBC in 2019 and her B. A. in History from the University of Washington in Seattle.

* * * * *

It was five months after my graduation from UMBC’s M.F.A. program when I decided to fulfill a promise I made to myself years ago. When you finish your M.F.A. you can focus on languages again.

For months after graduation, I had worked on drafting proposals for every grant and research opportunity I could get my hands on – including a massive, time-consuming Fulbright application. I found myself caught in a limbo of countless freelance contracts, part-time gigs, and waiting tables. At first it was exciting, the idea of not knowing where I could be in the next month. But it soon turned into a series of disappointing holding patterns. I was too afraid to commit to anything long-term just in case I was awarded one of these opportunities. This became a slippery hope slope, and by October I was starting to feel…depressed.

One day, I was reviewing some old journals and a piece of advice from someone I love popped out at me. It read, “You don’t have to have it all figured out all the time, Leah.” I instantly felt a weight lift off my chest and thought, “That’s it. I’m going to Italy. I’m going to study Italian, and I’m going to start making art again.” With the small savings I had cobbled together from this array of jobs, I bought a one-way ticket to Italy.

IL DOLCE FARE NIENTE

By early January, I was lucky enough to be living with family friends – Angela and Antonio and their children Federico and Rebecca – in Bologna, a small Medieval city in the North of Italy. I was finally going to lean into Il Dolce Fare Niente (the art of doing nothing) and attempt to scurry out of the hamster wheel of this life.

In between taking the bus to my language lessons, wandering around the city, and sharing daily life with my family, the first whispers of the COVID-19 panic began to permeate the airwaves. We were listening to the news as we prepared for dinner one evening. I missed a sentence that the announcer reported. “What did she just say?” I asked Federico, the eldest son, who is twenty years old and currently in medical school.

“There is a new virus in China,” he replied to me. At that moment I thought, that’s strange. I hope it doesn’t harm a lot of people. We finished dinner and the whole family squeezed onto the couch to watch Angela’s favorite soap opera, Un Posto al Sole.

WHEN IN ROME

I considered hopping all around Italy after my language lessons were finished: Venice, Milan, Verona, Siena, Florence, Rome, Naples, but a little voice in my head said, Don’t do that, just go to Rome. There had been three cases of coronavirus in Rome by the end of January. However, contract tracing had been done, and the three patients, including two Chinese tourists, were isolated at the hospital; all three had recovered. I believe this was a major news point that led many Italians, and me, to believe that this virus would not have a large effect, and that if you did get sick you would most likely get better. There were no other reports of COVID-19 in Rome, yet, so I traveled to the Eternal City on February 10.

I love Rome, but I guess that would be no surprise knowing I received my undergraduate degree in history. I know this ancient city has its faults and complications, but loving something means loving all of it. Traffic there is horrible, it is difficult to navigate, and large portions of the busy sidewalks are currently overrun with trash. But despite all that, Rome is the most magical city. Time unfolds differently there; the ancient meets the contemporary and pours into the streets, and this coupling of lifetimes is embedded in the energy that floats through the urban landscape.

I let myself wander for ten days, discovering new treasures and previous haunts. On Valentine’s Day, my favorite holiday, I visited the relic of Saint Valentine, climbed the hill to the orange grove of the Aventine, and wandered into the church of Santa Sabina where a group of students surprised fellow tourists by slowly flowing into song. I treated myself to cappuccinos in cafes in the morning and stumbled into bookstores in the evening. Ruins appeared in grand and simple ways, fountains glowed at night and lit my way as I roamed. I overheard conversations in Italian and felt proud of myself when I could understand half of it.

I made friends with a woman named Sabrina, who owned a small nail salon next to my apartment. At one point we discussed the virus. “Sei preoccupata? (Are you worried?),” I asked her. She paused for a minute and replied, “Un po’ (a little).”

A NEW WORLD IN BOLOGNA

After my final cappuccino at one of my favorite cafes, I packed my things, took the bus to Termini Station, and headed back to Bologna on Saturday the 22nd. That Sunday morning, I visited the MAMBO and discovered Daniela Comani’s work for the first time. She moved to Berlin in 1989 and kept a diary of her life. Wow, what a time to live in Berlin, I thought.

Around the dinner table that night, it was announced that all the schools, universities, cinemas, libraries, and museums of Bologna would be closed starting on Monday. Neighboring states were experiencing rapidly spreading outbreaks of COVID-19. In Milan, the police had barricaded the city, and the trains between Italy and Austria had been shut down. Davvero?! (Really?!)

Within the span of a few days, the energy around the coronavirus has shifted. One of my best friends from high school texted me. She and her husband were supposed to go to Milan the following week and she asked my opinion. “The city is police barricaded, everything is closed, La Scala is closed. You have to cancel,” I told her. It was hard for her to believe at first but after some convincing she conceded. I had already planned on coming home on Tuesday, February 25th, for another small trip planned with friends, and I am still shocked at the timing.

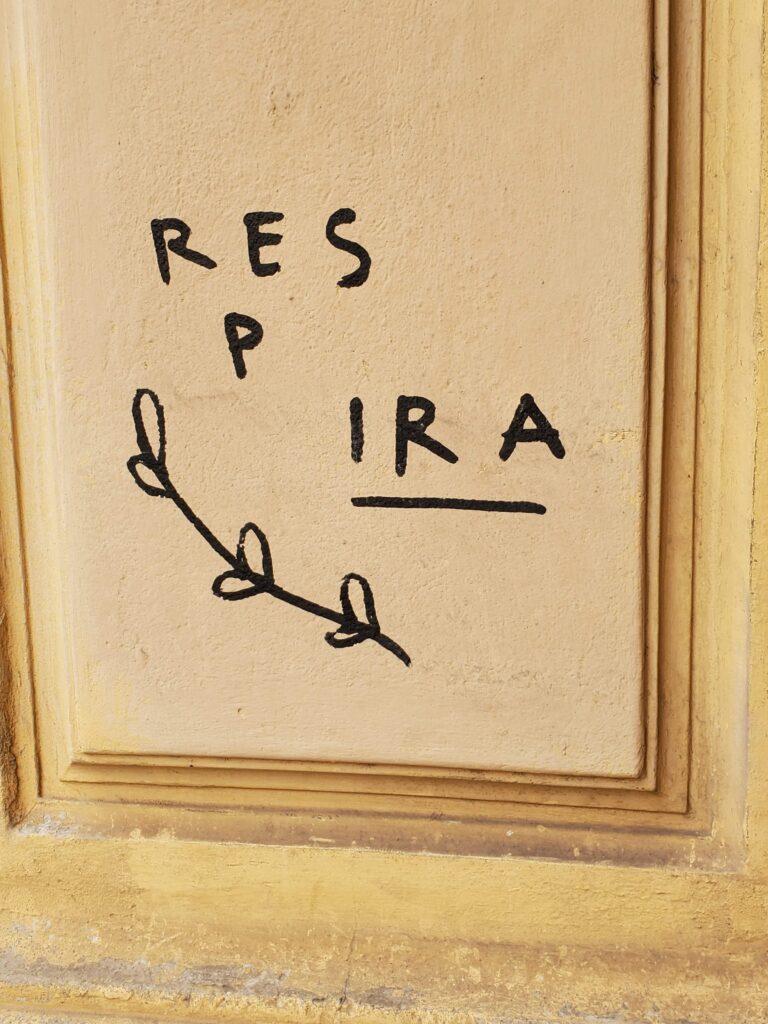

For my last day in Italy, I took a food tour of Bologna; there were only three people. Our tour guide shared with us that she hoped the closures would not affect small businesses, and she hoped they could still do tours. Bologna was not very busy that Monday and I thought about how the city had slowly been making its way into my heart with its painted ceiling porticos, talking walls, hidden canals, and frescos of hell.

When I came back from the tour, Federico and I watched the news. He told me he was worried. The hospitals in the North of Italy could handle this, he said, but if it spread to the south… We were both glued to the television for what felt like hours. “We have to stop,” I tell him. “This will make us crazy. There is nothing we can do right now.” He agreed with me and we turned it off.

After my final dinner with the family, I met some friends at a bar to say goodbye. Most of them were not worried. Everyone thought it would pass in a week or two. I called the airline that Monday night and they assured me that the flight would still be taking off in the morning.

SAYING GOODBYE

Tuesday morning, Angela and I sat together at the kitchen table, holding hands and holding back tears as we said our goodbyes. I hugged everyone and Antonio drove me to the airport. I was nervous for the entire two hours that I sat in the airport in Bologna.

I was shocked by what happened next: Nothing. At each check-in point in Bologna and Frankfurt, someone asked me if I had been to China in the last two weeks. My check-in point in Houston did not ask me any questions. There were no temperature checks, no hand sanitizers, no discussions of the growing outbreak in Italy.

I arrived home in Baltimore that Tuesday at midnight, glad to be home safely on one hand, but with an impending sense of worry and concern on the other. I knew what was coming; I could feel it in my body.

LOCKDOWN

On March 9, the entire country of Italy was put on lockdown. On March 12, I visited the Baltimore Museum of Art with a renewed sense of urgency. I knew that this would be the last time I would have a chance to see the work promised to the Baltimore community. The BMA vowed that 2020 would be a year dedicated to women artists, local and international.

I viewed Howardena Pindell’s Free White And 21, wandered inside Katharina Grosse’s Is It You?, felt moved by Valerie Maynard’s Lost and Found, and was mesmerized by Ana Mendieta’s Blood Inside Outside all over again. (Mendieta’s work has been an influence for years and I referenced her in my M.F.A. thesis.) I thought about how much she loved Rome, the pieces she created there, and that she also dreamed of building a life in the Eternal City.

We live our lives in layers, through time and space. I thought about how all these women used art as their medium to express their personal and political experiences. These works create spaces to reflect on pain, trauma, oppression, and offer to guide the viewer into sacred conversations on how to bear witness to these hurts and how to heal.

A deep sense of sadness filled me as I walked down the marble steps and left the museum. I knew that we would soon be living in a world without direct access to art, without shared spaces, and in a sense, without each other. I thought about how this would hurt the already disenfranchised more than most, and how our government is not prepared to handle this emergency. The BMA closed soon after, and one after another many institutions and businesses followed.

A TIME FOR REFLECTION

As I look back on my journey, these thoughts remain. May this unprecedented challenge lead us to a period of reflection. This is the time to take note of the national and international systems that have been broken – many have not sufficiently served their communities for centuries.

Perhaps this will lead to a new way, new leaders, and a new series of systems where the primary focus is the health, safety, and happiness of communities and not volatile markets which make the rich richer and the poor poorer. May we start revolutions from our bedrooms and living rooms, and imagine using the rubble of this time to build a world without poverty where everyone has equitable access for healthcare, knowledge, and art.

May there be creative work that comes out of this period, which gives ourselves time to mourn and also offers some solace. And may this time bring an awakening to just how connected we all truly are.

* * * * *

All images courtesy of Leah Clare Michaels. Header image: Piazza Santo Stefano in Bologna, Italy.

Tags: CAHSS, GraduateSchool, IMDA, Resilience