Most people wouldn’t guess horseshoe crabs—ancient arthropods with hard, round carapaces and long, spiky tails—when asked what animals you might find in a K-12 classroom. But Jessica Baniak ’23, biological sciences, is collaborating with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to shift kids’ perspectives of the alien-looking critters and create opportunities for inquiry-based learning.

Today, Baniak is a student in the ICARE program, an environmental science master’s program led by UMBC biology professor Tamra Mendelson. ICARE students study local environmental issues and include community partners on their master’s thesis committees.

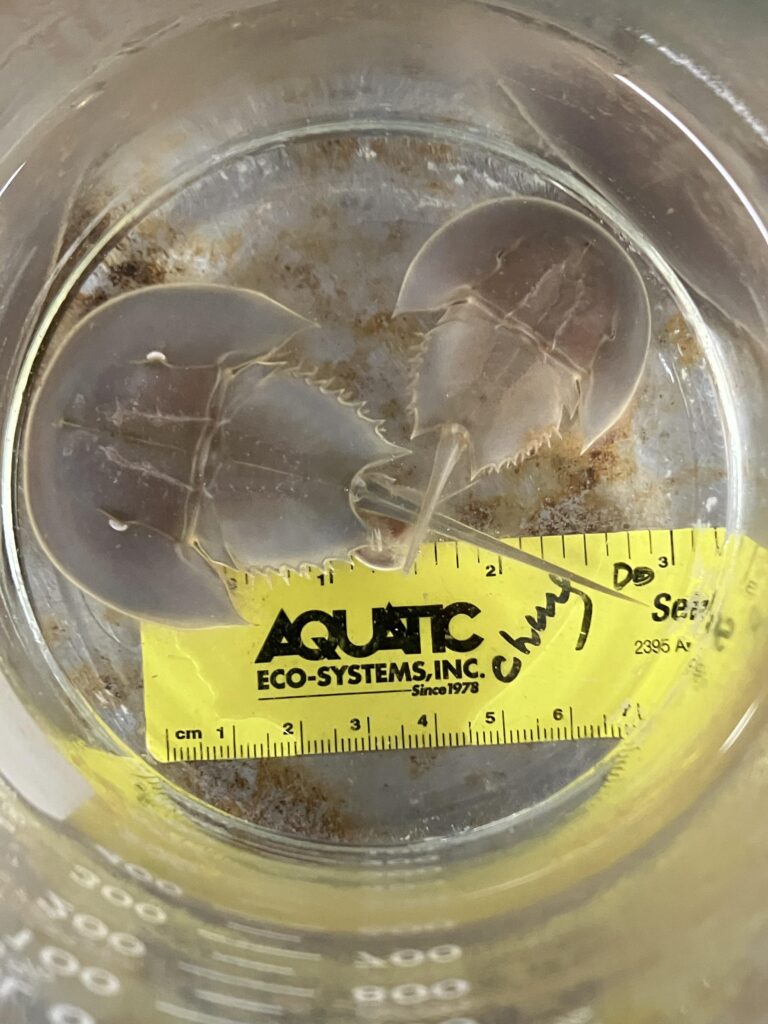

Horseshoe crabs congregate on Maryland and Delaware beaches to mate each spring, and the last two years Baniak has collected some of their eggs with a research permit from the Maryland DNR. Each female can produce upwards of 20,000 eggs. Baniak takes the eggs back to a lab at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology (IMET), a multi-institution research facility on Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, and raises them until they’re about a centimeter across.

Then Baniak delivers the baby crabs to elementary, middle, and high school classrooms in Howard, Carroll, and Baltimore counties. This year, 10 schools received crabs. Some teachers use the crabs in their curriculum, and some crabs are tended by student environmental clubs. Students run basic experiments that develop their science reasoning skills, like comparing growth rates in different hatchery setups.

Finding the sweet spot

It’s tricky to successfully raise the crabs to adulthood. Baniak visits each classroom a couple of times a year and makes suggestions to improve the crab habitats. Factors like feed, temperature, salinity, and more play a role in their survival. For her master’s research, Baniak is working out the ideal setup for successful crab-rearing with a focus on temperature. Higher temperatures produce faster growth, but some baby crabs perish in the heat. Cooler temps cut the mortality rate, but slow growth.

Baniak’s goal is to find the sweet spot that produces the most healthy crabs in a short amount of time. Why does efficiency matter? Because eager students aren’t the only ones interested in raising crabs.

Companies extract a compound from horseshoe crab blood that is used to detect bacterial contamination in pharmaceuticals. The blood can’t be harvested until the crabs are about 10 years old, Baniak explains, so raising them in captivity isn’t economical (it’s also challenging). Instead, reintroducing young crabs to their natural habitat is “a way that companies can help mitigate how much they’ve taken out of the wild,” Baniak says. Baniak’s work will help optimize these reintroduction programs for the industry—and at the same time, give kids a unique learning opportunity.

‘Everything all at once’

As a child, the National Aquarium in Baltimore—directly across the pier from IMET—inspired Baniak to pursue marine biology. Today her experiences range well beyond horseshoe crabs. As an undergraduate, she had a summer internship at an oyster hatchery. “During the breeding season—that’s when you work really long hours,” she says. “You have to do everything all at once.”

Counting surviving oysters, mating specific oyster pairs, and cleaning tanks—all while squeezing in work on experiments running at the hatchery—filled her days. One project involved developing a protocol to anesthetize oysters, which made it possible to collect tissue samples without killing the oyster. Baniak also assisted with the hatchery’s softshell clam initiative.

For another internship, she worked at the Maryland Pesticide Education Network, which promotes safer alternatives to harmful pesticides. During the academic year, she found time to participate in UMBC’s tae-kwon do club and play club volleyball.

Sharing the joy in science

After she graduates with her master’s next spring, Baniak hopes to move on to a role in a federal agency like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. She wants to continue to contribute to outreach programs like the horseshoe crab project.

“That’s my motivation for continuing in science, because I want to make more programs like that,” Baniak says. “I like ICARE because you’re working with other people in the community and not just researching a really niche subject.”

After she transferred to UMBC during the pandemic to be closer to home, UMBC faculty members helped her stay committed to her biological sciences degree. Maggie Holland, professor of geography and environmental systems, “brought back the joy into science after returning from online learning,” Baniak says. “She seemed to genuinely care about me as a student and about the subject she was teaching.”

Mendelson, too, made an impact. “She’s put a lot of effort into the ICARE program and wants to see all of us succeed,” Baniak says.

At the end of the school year, Baniak will travel with the students to release their horseshoe crabs at Sandy Point State Park and watch them wriggle across the sand and swim into the Chesapeake Bay, heading for life’s next phase.

Tags: alumni profile, Biology, CAHSS, CNMS, Fall 2024, GES, ICARE, IMET