Founding UMBC faculty across disciplines reflect on building a new public university.

By Richard Byrne ’86

UMBC opened its doors on September 19, 1966. But as concrete was poured and red bricks were laid, founding chancellor Albin O. Kuhn and founding dean of faculty Homer Schamp were also recruiting faculty members for a new research institution.

In a 1994 oral history interview conducted by Ed Orser, emeritus professor of American studies, Kuhn observed that adventure and ambition were his key selling points to recruits.

“[T]hat was the thing we talked about a lot when we were trying to attract original faculty and staff,” said Kuhn. “’Want to be a pioneer? Come join us. You can develop and help to make it what it will be…. It wasn’t a bad thing to get that kind of person.”

Founding faculty members of UMBC remember that desire to forge new trails and build as a powerful lure.

“The thought of coming to a new university was very attractive to me,” says William Rothstein, emeritus professor of sociology, and one of the professors hired for the university’s opening day.

“It was exciting to think about starting a program,” says Walter Sherwin, emeritus professor of ancient studies. “There was no one really over me. It was pretty heady stuff. It was all so exciting that I never thought about the risk.”

And as UMBC grew, it attracted more top-notch young faculty members – many of whom built lengthy careers in research and teaching at what was then the University of Maryland’s newest campus.

“I knew I was coming to a research university,” says Marilyn Demorest, emerita professor of psychology, “because it was the University of Maryland….We were University of Maryland faculty. And we were held to those standards.”

“It Was a Great Experiment”

Kuhn and Schamp initially organized UMBC into clusters: humanities and arts, social sciences, life sciences, and mathematics and physics. It was practicality at work: UMBC was too small to have full-fledged departments.

Finding faculty to meet the demand created by baby boomers also had an impact. Even established universities struggled to fill their professorial ranks in 1966. For many founding professors, UMBC was their first job.

Robert Burchard, emeritus professor of biological sciences, arrived on campus in January 1967, fresh from the Peace Corps, where he had been teaching microbiology in Nigeria and doing research on tsetse flies.

Burchard recalls that creating a new biology curriculum from scratch was invigorating: “It was a great experiment. And we were excited about what we were doing.”

Sherwin recalls that in the early years, offices were assigned by lot, and professors from various disciplines mingled together. “I enjoyed interacting with people outside my area,” he says. “We were in this together, and a lot of the conversation was not specific to discipline, but specific to making things work.”

Charles “Chuck” Peake, emeritus professor of economics, arrived in September 1967. “We had this idea we were going to build something,” he says.

Peake had an office in the “Gray House” that once stood outside Hilltop Circle near today’s athletics fields. He recalls that some classes were held in the Hillcrest Building that overlooked campus. “I remember walking up the hill past apple trees to get to classes,” he says.

The newness of the university, says Rothstein, also meant that “there was nothing to put your feet on. Everything was up for grabs.”

That feeling persisted through the university’s early years. “UMBC was an immense contrast to what I was experiencing in graduate school at Harvard,” says Joan Korenman, emerita professor of English and women’s studies, who arrived in 1969. “It was like a breath of fresh air. Everything was wide open and ready for discussion.”

UMBC asked Korenman if she was interested in a lecturer position in English. But at an interview, she indicated an interest in an assistant professor position. That was the position she was offered. Advancement was quick. Like many of her colleagues, Korenman discovered that the freedom to build had other obligations when she was appointed as an area coordinator soon after her arrival.

“Young faculty were expected to take on more administrative responsibilities,” she recalls.

“We Can Do This!”

Kuhn excelled in securing resources from the University of Maryland and state government. And as new students swelled the university’s enrollment, construction of UMBC’s physical campus was matched by an expansion of the faculty orchestrated by Schamp.

“I remember talking to Kuhn,” says Rothstein. “He told me: ‘I bring the money in, and Homer spends it.’”

Faculty took advantage of the opportunities. Jay Freyman, emeritus associate professor of ancient studies, landed at UMBC in 1968 with a Ph.D. in Classical Studies from the University of Pennsylvania. He says that the atmosphere at UMBC “was the same kind of attraction that someone feels when they go to a startup in Silicon Valley. It’s the ground up. There’s nowhere to go but up. You’re going to make something there that wasn’t there before. We could do some things that were offbeat. We could try things.”

Freyman had ideas about where his discipline was headed – and how he and his colleagues needed to adapt. “We recognized that a traditional ‘classics’ program would not survive. Latin and Greek. Those were the departments that were getting dumped,” he says. “We realized that in order to survive, we had to have a broader appeal than just linguistic and literary. So we incorporated history and archaeology. We were one of the first departments in the country to do this.”

Ancient studies faculty members were also at the forefront of another great UMBC tradition: Study abroad. UMBC faculty had already leapt ahead of many other universities in creating a January session (dubbed the “minimester”). But it was Sherwin, Freyman and their colleague Rudolph Storch, emeritus professor of ancient studies, who organized and led trips to Italy and Greece in the first years of the university.

For many of the students of that era, it was a mind-blowing adventure. Sherwin got the idea from a Fulbright fellowship he had at the American Academy in Rome that combined lectures and visits to historic sites. “I came back and told my colleagues, ‘We can do this! We will establish a program abroad.”

UMBC professors didn’t stop at curricular innovations. Burchard’s passion for environmentalism and pedagogy intersected when campus planners turned their gaze to Pig Pen Pond – a body of water that remained from the campus’ days as farmland – and planned to pave over half of it.

“The biology folks looked at that as a good teaching resource,” says Burchard. “I raised hell about it.”

Burchard and others succeeded in saving Pig Pen Pond. Today, it is a key element of the Conservation and Environmental Research Areas [CERA] – and it remains as a locus for campus research.

“Pushing for Quality”

UMBC did have growing pains. The administration and the faculty debated which courses should be required for graduation for a number of years. The denial of tenure to some popular professors hired in UMBC’s early years also elicited student protests.

And though UMBC was the first university founded in Maryland in the post-segregation era, racial disparities in enrollment, employment, and curriculum at UMBC quickly became apparent.

In May 1969, a committee created by Kuhn to achieve “significant integration of minority groups at UMBC” offered an array of proposals to the chancellor, including creation of a department of “Black Studies.” A year later, the university’s Black Student Union and a caucus of black faculty and staff pressed the case for change more urgently, and by the end of 1970, UMBC had hired Elechukwu Njaka from Tuskegee Institute to build a program with the rank of a division within UMBC.

Among the faculty who built the program was Daphne Harrison, emerita professor of Africana studies, and founder of UMBC’s Humanities Forum. “I found that UMBC was quite different from many institutions,” she recalls. “The attitude was that you as a professor are important, but the professor also has to work.”

Harrison taught a wide array of courses, but she says that her insistence on rigorous interrogation of notions received from mass culture was at the heart of the endeavor: “Young people were getting a lot of information but they didn’t know how to vet it. That was one of the things I remember doing with them. You have to know whether or not what you’ve got is real. You have to check to see whether it is accurate.”

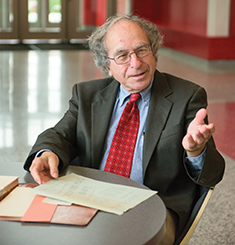

In 1975, UMBC hired Willie Lamousé-Smith from Syracuse University to head the program. A Ghanaian scholar who received his doctorate from the University of Münster, he was lured from a tenured positions in Syracuse’s Afro-American studies program department and as associate director of the East African studies program in its Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

Hiring Lamousé-Smith from a prominent research institution was one signal that UMBC aspired to raise its profile in the humanities. But demanding the best from students and helping them find their place in campus life was equally important to him.

“I do not intend to make people comfortable,” says Lamousé-Smith. “And that is my policy when I am teaching. People have to take their studies seriously. It’s only a short time in the person’s life. And yet the person’s whole future is going to depend and rely upon what that person does in that short period. So if I do not help the person to achieve their highest level, I feel I have not done well.”

Other key academic programs emerged. The late 1960s and 1970s was a busy era in experimental psychology – and psychology quickly became (and remains) one of UMBC’s most popular majors.

Demorest recalls hearing about “that place in Catonsville,” as she finished graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University and post-doctoral work at the University of Pittsburgh. She admits it didn’t sound appealing at first.

In 1972, however, she was recruited by the late Aron Siegman, a professor of psychology at UMBC. She reluctantly came for an interview and was surprised. “I spent two absolutely glorious days,” she recalls, “being passed from one faculty member to another, talking about every different type of psychology…. So I ended up coming to ‘that place in Catonsville’ really excited about being here.”

Psychology launched one of UMBC’s first graduate programs: a community clinical psychology master’s program created in 1974.

Demorest says that the burgeoning quality of UMBC’s faculty in that era later helped her, as vice provost, to recruit others to campus to join her. “I would invite [candidates] to look at the credentials. We were recruited from first-rate institutions from Columbia and Chicago and Hopkins….and so we came in with the standards we were held to, and so those were the standards we held our students to. We didn’t know any different.”

“You Can’t Do That with Just Science”

Psychology was not alone in its prominence. Many founding faculty point to the arrival of the late Martin “Marty” Schwartz as the coordinator of the biology division in 1969 as the beginning of UMBC’s ambitious push to make grant-funded research an engine that would propel the university into maturity and excellence.

“The scientists were clearly the most hard-nosed in terms of academic research,” says Rothstein. “And making UMBC have a name for itself as a quality research institution, the sciences were clearly leading the pack.”

Phillip Sokolove, emeritus professor of biology, arrived in 1974 and found himself in the center of a busy hub of research activity spearheaded by Schwartz.

“He was a man with vision,” Sokolove says. “My interaction with him was extremely positive as a young professor. He was quite clear what the nature of the department was, and that we had to become one of the premier research departments on the campus, along with chemistry. Since Swartz was chair of both departments, and of the biochemistry department, he adds, “Schwartz saw them as natural allies.”

Sokolove says that Schwartz was driven to get the best from his faculty. “He was able to give his faculty the time to do what they needed to do,” he recalls, “and then pushed them hard to do it. And when somebody came in and couldn’t cut the mustard he was ruthless. Not ruthlessly himself. What he did was turn the faculty into a well-developed jury of peers.”

Lamousé-Smith, who served with Schwartz on UMBC’s Council of Divisional Deans with Schwartz, recalls that he pushed for academic excellence and leadership with equal vigor. Schwartz was a “strong personality” who often played hardball over resources in meetings of academic leadership. “He would chew you up and spit you out and then embrace you and kiss you on the cheek,” Lamousé-Smith says.

“But Marty Schwartz was not just pushing for his own department, but for every department,” Lamousé-Smith continues. “Marty Schwartz, and his impatience, planted the seeds of pushing for excellence at UMBC.”

UMBC now boasts a strong balance between research and teaching across disciplines. That strength in all areas is part of its founding chancellor’s blueprint. As Kuhn told associate professor of history Joseph Tatarewicz in an oral interview conducted in 2001, UMBC was created at the moment when influential University of California system president Clark Kerr touted America’s universities as a ‘prime instrument of national purpose.”

Kuhn argued that a modern university “can’t do that with just science. You have to do that with understanding people. You have to do it with understanding the real drive that’s involved in the humanities and arts. And when you put it all together, it can be very forceful. Without all of it together, you won’t get there.”

“That place in Catonsville” – as Demorest fondly refers to it now – has come a long way toward fulfilling Kuhn’s vision because of the strength of its founding faculty, and the professors who have followed them to this day.

* * * * *

From the Editor:

The cover of the Summer 2016 issue of UMBC Magazine you may have received in the mail has a significant error for which I would like to personally apologize to our readers.

In our image of professors then and now, the magazine cover mistakenly paired a recent photo of Professor Emeritus of Africana Studies Willie Lamousé-Smith with an archival photo of longtime UMBC professor of Africana Studies Jonathan Peters from the Albin O. Kuhn Library’s collection of university photographs.

Our magazine team has redesigned the magazine cover digitally to pair Professor Lamousé-Smith with a correct image – which we have posted on the magazine website, to our Facebook site, and to our wider UMBC Alumni site. But I did not catch the error before the magazine was sent to the printing press and then on to our readers.

As you will discover both in the “Editor’s Note” to this issue and in the story about the founding faculty of the university (“So You Want to Be a Pioneer? – read below this note), Professor Lamousé-Smith’s wisdom and spirit have played a significant role in UMBC’s rising fortunes as a university through the decades. I have reached out to Professor Lamousé-Smith personally to apologize for this error.

The many contributions and achievements of our faculty and staff are a significant part of what we are celebrating this year in UMBC’s 50th anniversary. It has been part of the mission of UMBC Magazine to tell these stories accurately. In this case, we let our readers down. We hope this note serves both to correct the record and express our regret for the error.

Richard Byrne ’86

Editor, UMBC Magazine

Tags: Summer 2016