Family stories, told honestly, reach people in ways that reams of advice and pages in history books cannot. When personal narratives reach the classroom, students respond by opening up, say two professors who have published memoirs of their family tragedies as a way to process their grief and share their stories.

“I believe that writing personal narratives and sharing my own family’s stories helps build trust and rapport in the classroom,” said Aharona (Roni) Rosenthal, director of Judaic Studies at UMBC. “Writing personal narratives can serve as a model for students and encourage them to listen to their grandparents’ stories, embrace their own family’s traditions, and find their own voice in writing.”

Write about the darkness and the light

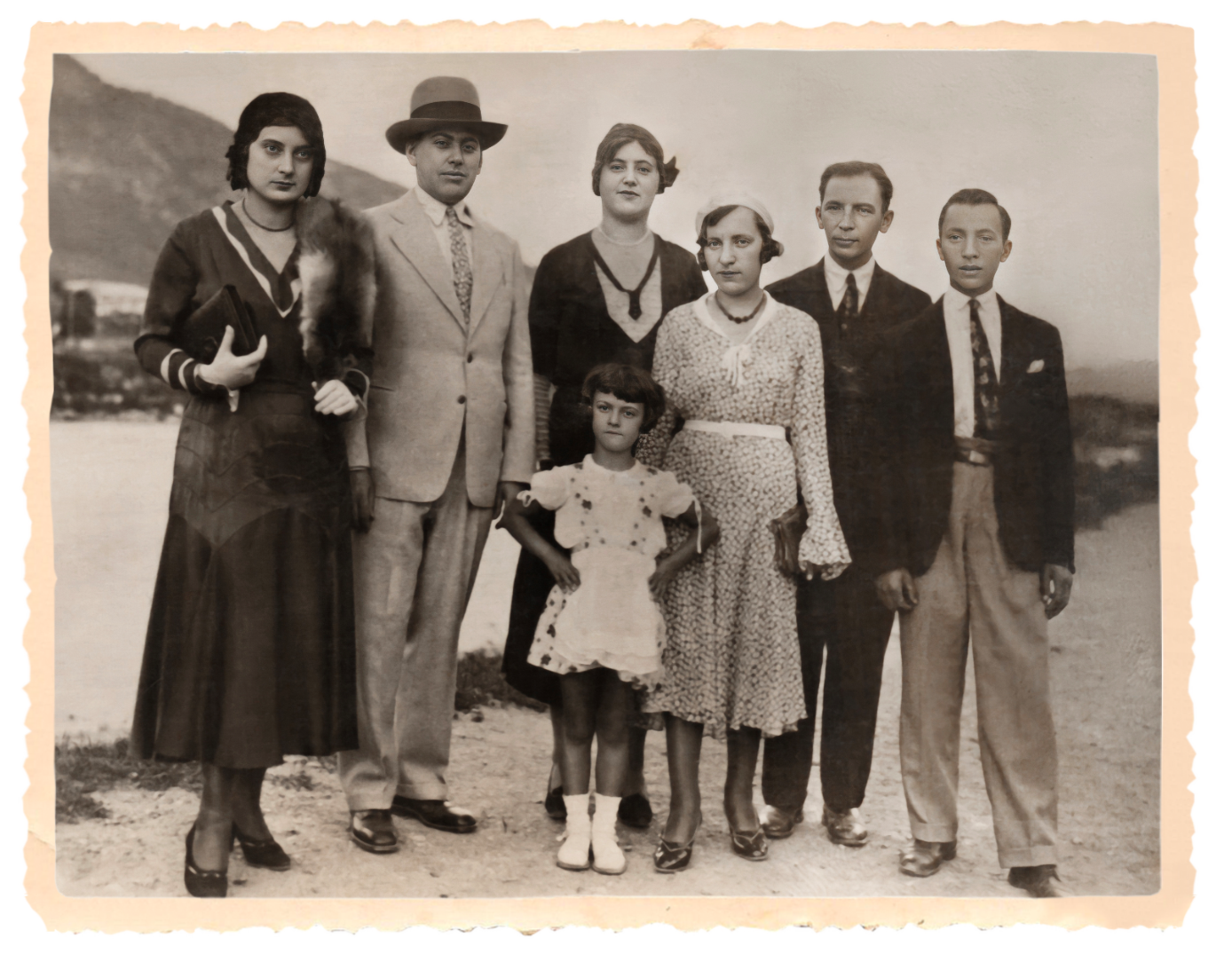

Rosenthal, who self-published her family’s history last spring as Where the Lilacs Bloom Once Again, remembers her great-aunt Friddie arriving for a visit to the family in Israel. With her huge laugh, her bright red nail polish, and her scarred hands and face, Friddie would wear thick makeup, pull white gloves over her hands, and paint the undersides of her nails to hide the permanently blackened nails.

Rosenthal recorded her father telling family stories about Friddie, kept for 13 years in secret prisons and labor camps in Romania during World War II and then under the Communist rule, where she was tortured and forced to dig the canal from the Danube River to the Black Sea. When her father, Yossi Rosenthal, died a few months after telling her that history, Rosenthal returned to Israel and found on her father’s desk a photo album, a partially finished family tree, and a note from her father, asking her to tell more widely the story of their family.

Rosenthal spent 12 years researching and writing her family memoir. Along the way, Rosenthal found long-lost family members, learned the fate of others, and gathered material that she now shares in her classes at UMBC, especially in her unit on the Holocaust in her Hebrew literature class.

One of the Rosenthal family stories tells of Friddie’s detainment in the labor camp, where she met a man through a chink in the stone wall dividing the men’s side from the women’s side of the camp. Friddie was looking for a cat who was slinking around the wall, and so was Mircea, the man she fell in love with, sight unseen.

“It was a miracle in the darkest place in the world, the scariest place in the world,” Rosenthal said, and after Mircea was released, he helped free Friddie and the couple married.

Narratives that stick with you

Rosenthal’s family tales are intertwined with atrocities in World War II, when Romania allied with the Nazis. Thousands of Romania’s Jews were slaughtered and sent to concentration camps. Rosenthal remembers her grandparents who, on every anniversary of a 1941 pogrom in Iași, would light candles under pictures of lost loved ones, but never speak about the massacre.

One of Rosenthal’s students, Moriah Thompson ’24, biological sciences, said she had known the history of atrocities in World War II, but that Rosenthal’s stories and primary sources brought that history to life.

“Seeing her pictures and listening to the letter her ancestors wrote, it was actually so absolutely incredible to see the history as it related to her family,” Thompson said. “The narrative that stuck with me the most was the letter her great-grandfather wrote about the pogrom he and his family endured. Being Jewish, we know the history and we’ve heard the stories. But hearing from a man who experienced it was so much different. I can’t imagine the fear he felt trying to keep his family safe, or his wife worrying about the children.”

Writing your story so others can find it

Nancy Shelton, a recently retired education professor at UMBC, knows the power of writing a personal story.

“I don’t believe you can teach kids to write without writing with them,” said Shelton, who researched literacy and taught potential teachers how to teach writing. So as a classroom teacher, then as a professor in the education department, she always wrote with her students during classroom writing sessions.

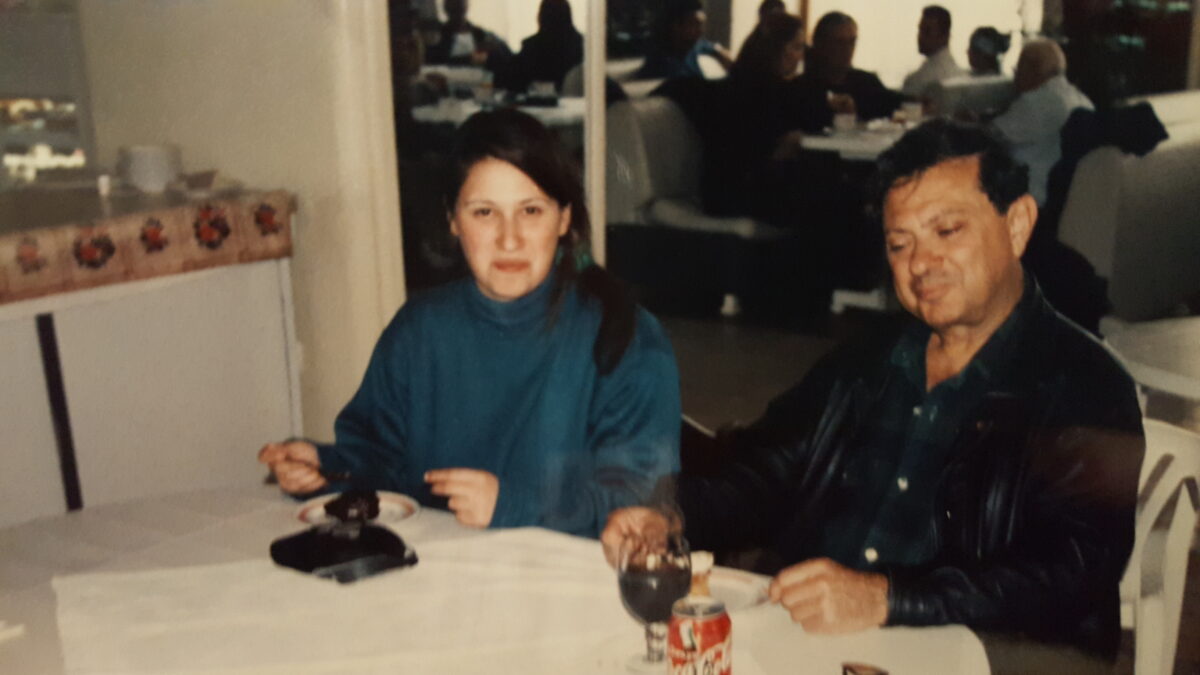

One winter day at their Florida vacation home, when she and her husband were both a few years from retirement, he was joking with her as he headed out to wash their new car. A while later, Shelton, who has hearing loss, heard her dogs barking frantically and found her husband prone on the kitchen floor, having a seizure.

“It literally came out of the blue,” Shelton remembered. At the hospital soon after his seizure, John was diagnosed with stage four cancer.

“A death sentence,” Shelton said. She called her sister who advised her to take notes during the medical consultations. As John slept in the evenings, Nancy sat by his hospital bedside and filled in her notes “as if they were data,” the kind she had collected for years researching schoolchildren’s literacy. Her notes, she said, were a way of handling her husband’s swift slide into illness, and finally death.

“I am a writer,” Shelton said. “I thought, well, I will write my way through this.”

As a reader, she looked for books with characters whose family members were dying of cancer, but she couldn’t find any she identified with. So she wrote one, 5-13: A Memoir of Love, Loss and Survival, published in 2016.

Writing can make you strong

“Being able to be a published author as a teacher of writing gives you credibility,” Shelton said.

In her education classes, Shelton read literature to her students, such as the first kiss scene from Rita Mae Brown’s autobiographical novel, Rubyfruit Jungle, or the definition of heaven by the narrator of Lovely Bones. Then she would ask the students to write in response. Often, the students’ writing was quite personal, exploring identity, family and memory.

The classroom, she said, turned into a safe space for writing, and for sharing. “I believe writing is something that exposes a part of us that would otherwise be hidden, and that exposing makes you very vulnerable, but also makes you very strong,” she said.

By Susan Thornton Hobby

Tags: CAHSS, cahssresearch, Education, Judaic Studies, Research