In the face of a harrowing national epidemic, UMBC researchers and alumni work to break through the darkness of opioid addiction and the stigma that surrounds its victims.

By Jenny O’Grady

On a recent rainy morning, a steady stream of men and women enters and exits Riverside Treatment Services in Rosedale. They look like anyone and everyone – a neighbor, a schoolmate, a grandparent – wandering in on their way to work, leaving with steaming paper cups of coffee. They are purposeful, upbeat.

“For many of them, we’re the one positive part of their day,” says center director Chuck Watson ’12, social work, who sees his clients at their lowest points, but also as they make life-changing breakthroughs through treatment. Trying to put a face on opioid addiction is impossible; it’s a disease that can strike anyone. With recent attention from legislators at the national and local levels, the race is on to stop the deadly effects of both legal and illegal opioid abuse.

“For many of them, we’re the one positive part of their day,” says center director Chuck Watson ’12, social work, who sees his clients at their lowest points, but also as they make life-changing breakthroughs through treatment. Trying to put a face on opioid addiction is impossible; it’s a disease that can strike anyone. With recent attention from legislators at the national and local levels, the race is on to stop the deadly effects of both legal and illegal opioid abuse.

At UMBC, researchers across disciplines are answering the call to help figure out unique approaches to studying the epidemic. Together, they are working to understand its causes, to tell stories of its effects, and to offer routes to early detection and treatment.

It’s emotionally grueling work with no real endpoint in sight, but all agree – it’s important work that has to happen. Lives depend on it.

Read more about Chuck Watson: “A Second Chance at Life”

When you think about how much data is floating around about each of us, it makes sense to guess that the right combinations of it – collected, sorted, and interpreted in just the right way – might help paint a picture of victory against substance abuse. But where do you start? How do you cut through it? And how can you package it so the people who want to help – legislators, first responders, and others – have the tools to make the best decisions?

For the last decade, behavioral health researcher Michael Abrams Ph.D. ’16, public policy, has combed data collected by public health systems with these precise questions in mind. As director of special research studies for The Hilltop Institute at UMBC, a non-partisan health research organization dedicated to improving the health and well-being of vulnerable populations, Abrams and others have helped entities such as the City of Baltimore Behavioral Health Authority crunch the numbers in a way that allows them to develop meaningful policy. Working with data from hospital admissions records, Medicaid, and the Maryland Department of Health’s Behavioral Health Administration, Abrams and his Hilltop colleagues have produced several reports related to opioid – use disorders and their effects on people and the systems that treat them.

“At Hilltop we do our best to use administrative data – that is, data designed to facilitate billing and payment – and other supplemental information to discern what is truly happening in the publicly financed health care marketplace,” says Abrams, who stays carefully objective in his work. “Our mission is very public service-oriented.”

“At Hilltop we do our best to use administrative data – that is, data designed to facilitate billing and payment – and other supplemental information to discern what is truly happening in the publicly financed health care marketplace,” says Abrams, who stays carefully objective in his work. “Our mission is very public service-oriented.”

In July, he and University of Maryland Baltimore School of Pharmacy professor Fadia T. Shaya, received a $50,000 Innovation Seed Grant from the UMB-UMBC Research and Innovation Partnership Grant Program to conduct a 15-month case control study of Medicaidaided youths aged 13 to 24 to explore whether prior exposure to prescription opioids is associated with subsequent opioid dependence.

“There are so many variables that go into…understanding what’s going on with something like addiction or with mental disorders more generally,” he says. “There are so many dimensions to these problems. It’s not just about biology, though biology is a big part of what makes these issues so compelling. But, addressing these problems has to consider many other factors including: income and economics, crime control, the practice of medicine, pharmaceutical marketing, interpersonal dynamics, education, and politics. This seed grant project lets us explore the medical antecedents to addiction, an important focus because many believe prescription overuse is a key driver of the overdose epidemic we are experiencing.”

Simultaneously, a UMBC-based group of interdisciplinary researchers – The Big GUI (Graphical User Interface) Data Group – has recently come together to tackle the specific problem of how to present the constellation of data related to opioid use, overdoses, and treatment in meaningful ways. Lead by Lee Boot, director of UMBC’s Imaging Research Center (IRC), and joined by researchers from computer science, electrical engineering, and elsewhere, the group is figuring out how a three-dimensional digital visualization might include data on overdoses responders contribute to on the spot, and to allow for the inclusion of contextual data – such as holidays, weather, or importantly, social factors that affect people’s lives – to give users a full picture of what addiction and recovery actually entail.

“Considering all the relevant factors makes it such a complicated problem that no one can wrap their brains around it,” says Boot, whose evolving software MapTu could help in that regard. In its current format, the software takes in pieces of data and projects them as floating shapes that can be pulled together to create meaning, and modified by collaborating users who can add narratives and video to tell the story of the data.

“[With this group,] we’re changing our pursuit from getting more information to figuring out what to do with it,” says Boot, who notes that as important as it is for practitioners to focus on the here and now, it is also useful to step back and ask what might be done to avoid another similar human tragedies in the future. Asks Boot: “What if you could visualize and actually make sense of all of it in one place? Imagine what we might learn.”

Deborah Rudacille is at the very start of her research journey, but it’s already piling up noticeably on her desk.

She calls it “the fishing expedition:” the Xeroxed pile of articles, the sifting through of factoids, the hand-written notes that might or might not pay off later. Over the coming year, thanks to the Guggenheim grant she won for her science writing, Rudacille will be neck deep in the studies and personal stories that will – she hopes – turn into a book or series of articles about substance use disorders as heritable diseases that affect the whole family, not just those who are addicted to alcohol or drugs.

“I never do seem to pick cheerful topics,” admits Rudacille, an otherwise upbeat professor of the practice in the English department, who has written about everything from the use of animals in research and testing, to autism, to the history of sex and gender revolution, and the ways technology contributed to the rise and fall of the steel industry in Sparrow’s Point.

“Each one of these has been sort of a subject, a topic, something that I was really just interested in, if not obsessed with, for a time or for my whole lifetime…things that I was curious about and needed for myself to learn more about, and at one point, realized that probably other people really needed more information about, too,” says Rudacille, whose personal interest in addiction has dug at her intellectually for years.

“Each one of these has been sort of a subject, a topic, something that I was really just interested in, if not obsessed with, for a time or for my whole lifetime…things that I was curious about and needed for myself to learn more about, and at one point, realized that probably other people really needed more information about, too,” says Rudacille, whose personal interest in addiction has dug at her intellectually for years.

With this new pursuit, she will interview families across the country dealing with addictions of all sorts – including opioids – to pursue a growing list of questions. Do personality traits – like impulsivity, risk taking, novelty seeking, and stress response – have genetic, or inherited, components? What role does a “family culture” play in recovery?

“It’s so very clear that this is a brain disease, that this is a family disease,” she says. “And that’s, I think, as much as anything else, the point that I would like to make and support by talking to researchers, by talking to affected people, by talking to family members, that we should not be conceptualizing addiction as a moral failing or a failure of individual control. It’s a disease.”

Although she’s just beginning her research, she’s already found some incredible statistics to jump-start her exploration. Sifting through the papers on her desk, she finds the one she’s looking for: an estimate that for every one addict, there are at least seven other people affected.

“And that makes sense to me…it’s in the family,” says Rudacille. “Because we’ve got parents, we’ve got children, we’ve got siblings, we’ve got spouses. And again, as I know from experience, it’s not just those relatives that are affected, but also aunts, uncles, cousins.”

Like Abrams, Rudacille doesn’t veer into the politics of her subjects. In the case of writing about opioids, so much of that has already been covered by other authors. But, she’s excited to contribute to a tradition of journalism that helps to shine a careful light on this particular piece of the puzzle, and the people who live it.

“I would say the big issue here is shame and stigma,” she says. “As a reporter, you feel an incredible responsibility to treat their stories with the respect and the dignity they deserve, especially when you are dealing with people who have been marginalized.”

Psychology professor Carlo DiClemente tells the story of a heroin addict who, upon hearing about a rash of people dying from fentanyl-laced heroin in Baltimore, asks, “Where can I get that? It must be good sh*t.”

In his more than 25 years of studying substance abuse and the motivations behind addictive behaviors, DiClemente has found one thing to be consistently true: If you’re not ready to change – really, truly ready – it’s just not going to happen.

“Every entry into and exit out of addiction is a personal journey,” says DiClemente, co-founder of the “Transtheoretical Model” of behavior change, and author of several books on the subject, including Addiction and Change: How Addictions Develop and Addicted People Recover. Understanding and addressing the addict’s motivations can mean the difference between success and failure.

DiClemente has seen this first hand in the substance abuse treatment programs he has run. Without knowledge of the addict’s mindset and motivation – in DiClemente’s model, he breaks motivation into the stages into pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance – a treatment provider can’t know where to begin.

DiClemente has seen this first hand in the substance abuse treatment programs he has run. Without knowledge of the addict’s mindset and motivation – in DiClemente’s model, he breaks motivation into the stages into pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance – a treatment provider can’t know where to begin.

“The problem is, with tobacco, and with the opiate addiction, people find it almost impossible to quit. It changes the brain. It impairs individual self-regulation, and it takes over their life,” making it difficult to know all that is really going on, he says.

“Some of the research is looking at people who are in different stages, so we can look at personal and even epidemiological data and try to understand where people are, if we ask the right questions.”

With the recent increase in opioid use, and knowing how many potential ways an addict might enter into care (or evade it), DiClemente has been developing and offering training for people in various jobs – medical providers, front desk employees at agencies and hospitals, social workers who make home visits, etc. – who could spot signs of substance abuse, and offer information about treatment as they come across it.

“A big thing is to really empower a variety of providers who come across addiction but aren’t really addiction specialists, on how to recognize and how to refer, and how to help motivate people to take the next step,” says DiClemente.

“If we can prevent someone from getting into the last stages of addiction, that’s really what we should be doing,” he says. “Early intervention is the best intervention.”

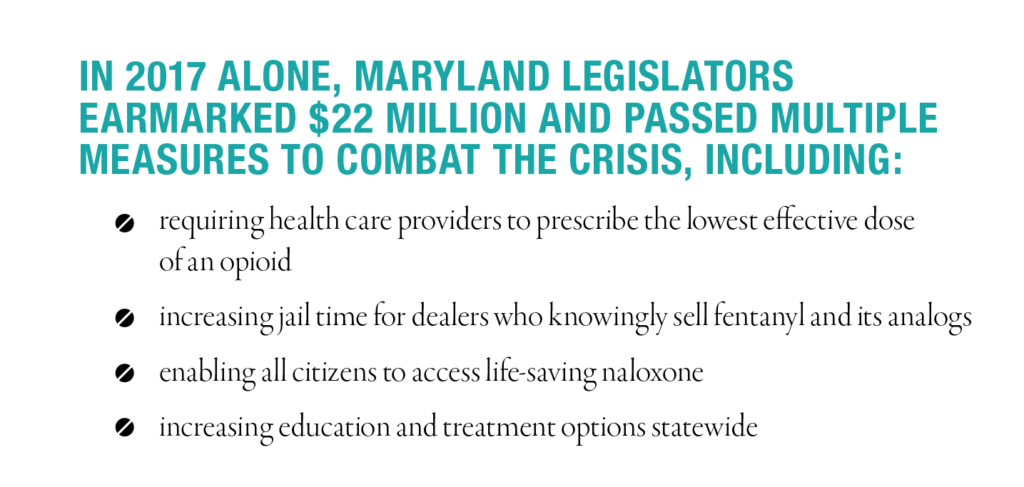

Info graphic information source: The National Institute on Drug Abuse: drugabuse.gov

* * * * *

Tags: Fall 2017