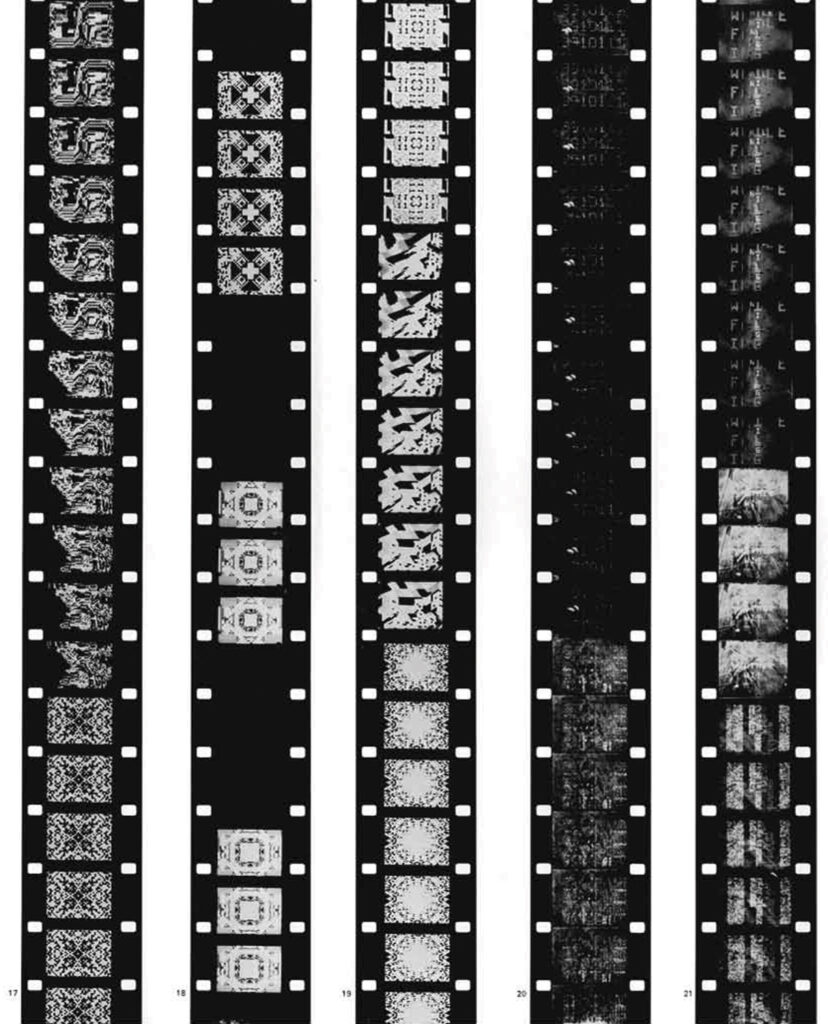

The film begins, a fast-moving montage of seemingly unrelated images: eyes, people dancing, an airplane landing, artillery, President Kennedy, wrestlers, a woman applying hairspray, all interspersed with wacky cartoon-like animated images.

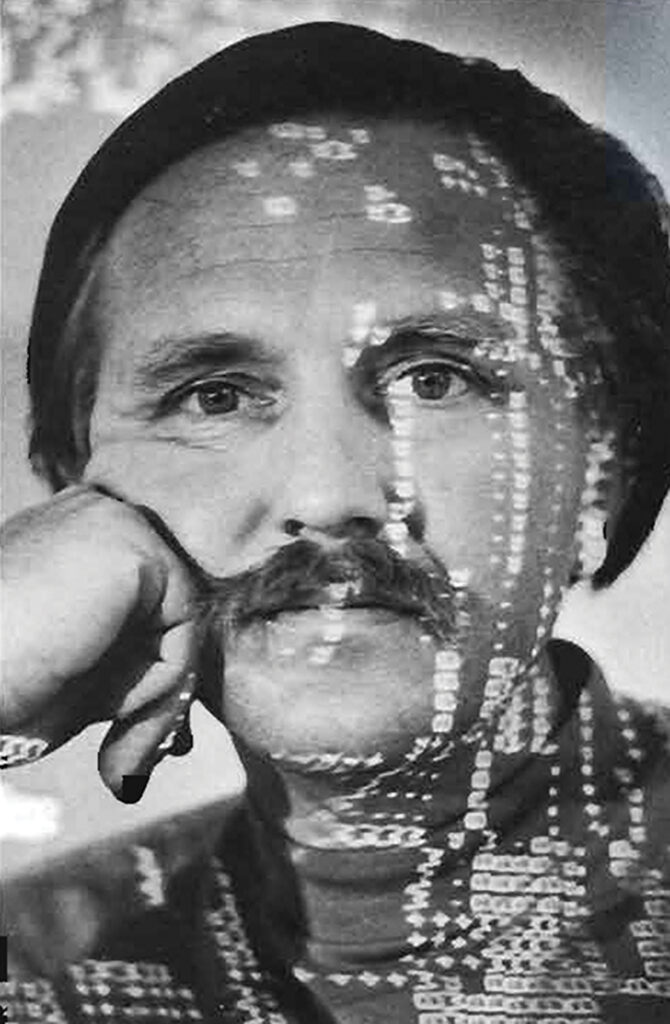

It’s the start of Breathdeath, Stan VanDerBeek’s experimental 1963 masterpiece that would influence a generation of artists, including Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam. VanDerBeek’s genius and visionary thinking—not only as a filmmaker, but also as a video artist, computer animator, and futurist—would earn him worldwide fame and, in 1975, a full professorship at UMBC, where he taught until his untimely death in 1984.

VanDerBeek’s vision can still be seen in the programs he helped found and the alumni he inspired at UMBC.

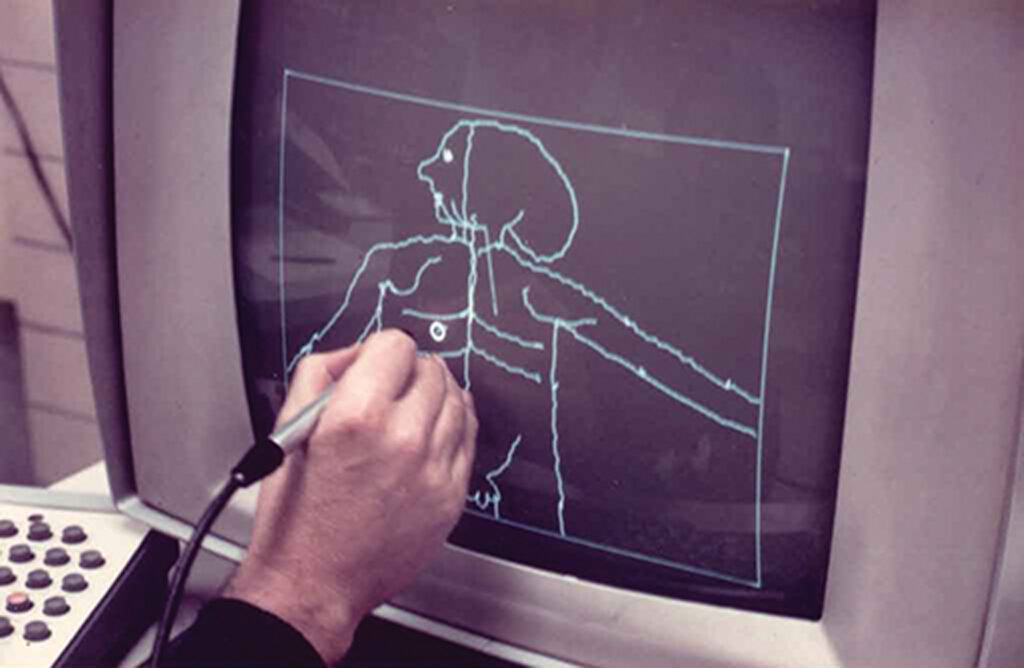

Underground Artist

Born in 1927 in New York to immigrant parents, VanDerBeek’s early interest in painting, architecture, and design led him to Black Mountain College, where he befriended pioneering composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and inventor Buckminster Fuller, all of whom were to prove deeply influential on the artist. In the early 1950s, working as a designer on the CBS children’s program Winky Dink and You—which featured plastic screens children could apply to the television and draw on with special crayons—VanDerBeek learned basic animation skills and, by 1955, began to create his own animated films. In 1959, he organized a New York film festival entitled “Films from the Underground,” and the term “underground film” was born.

Throughout his 30-year career, VanDerBeek was more than an artist; he became a visionary who thought beyond limits and boundaries, often dreaming up fascinating ideas that couldn’t be executed—at least in his lifetime. In 1980, midway through his tenure at UMBC, he imagined, “You’ll sit in your backyard and look up at beautiful paintings I and other artists will do for you on a 10,000 square mile screen of clouds. The strokes and colors will be images projected by laser beams. I call it ‘painting with light’ or optical painting.”

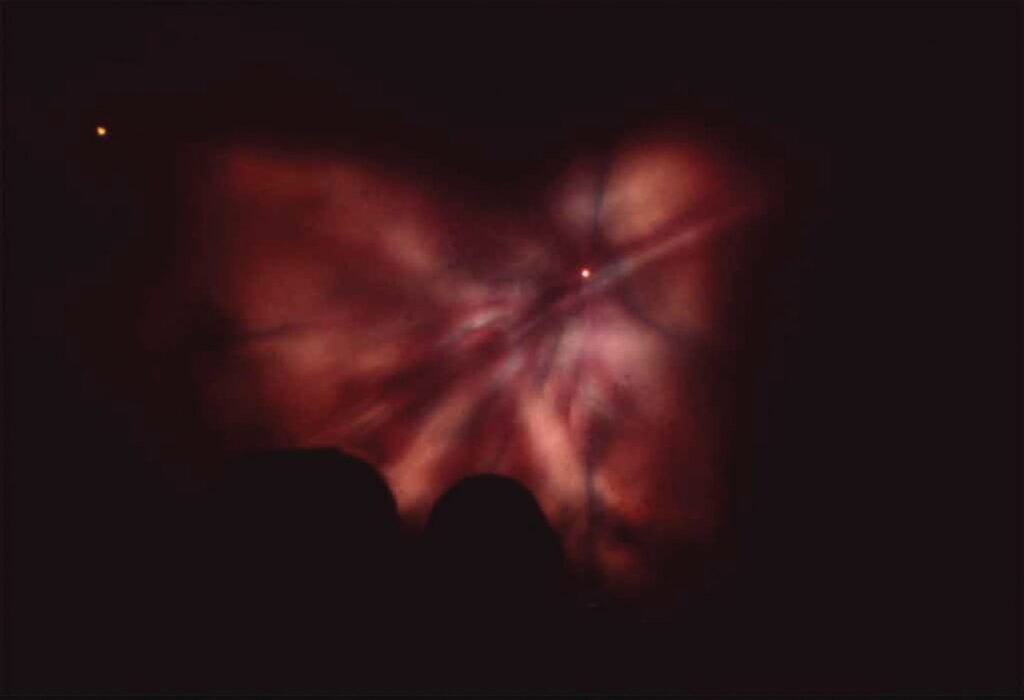

At UMBC, recalls Ellsworth Hall ’82, visual arts, the cloud projections were realized on a smaller scale. “A good friend of mine, Ed Hopf, with whom I’ve made films with since we were 13, helped Stan on his multimedia presentations. He would have film projected on the ‘smoke’ created by melting dry ice. At one point there wasn’t enough ‘smoke’ and Stan was in a hurry trying to coordinate some other aspect of the production so he grabbed the dry ice with his bare hands and threw it in the container to melt!”

For VanDerBeek, moving images weren’t only material for his artwork—they had the power to facilitate global understanding and to help the world move toward peace. In a manifesto, “CULTURE: Intercom and Expanded Cinema,” he wrote, “I propose the following: that immediate research begin on the possibility of a picture-language based on motion pictures; that we combine audio-visual devices into an educational tool: an experience machine or ‘culture-intercom’; that audio-visual research centers be established on an international scale to explore the existing audio-visual devices and procedures, develop new image-making devices, and store and transfer image materials, motion pictures, television, computers, video-tape, etc.; that artists be trained on an international basis in the use of these image tools…” He set forth ideas with the certainty that they could be accomplished and even needed to be accomplished.

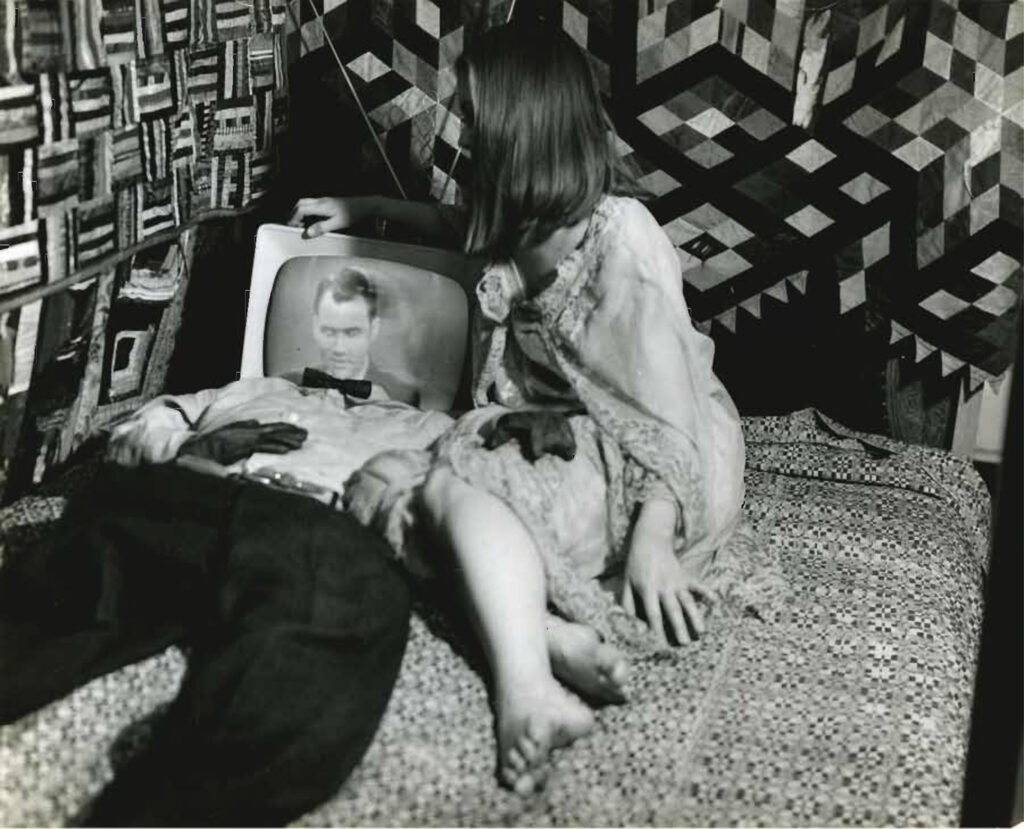

To facilitate that vision of global communication, VanDerBeek forged what was perhaps his best-known creation, the Movie-Drome. Located at Stony Point, New York, at the Gate Hill Cooperative (populated by the young VanDerBeek family in addition to others who had migrated from Black Mountain College, including John Cage, pianist David Tudor, and potter M.C. Richards), the Movie-Drome was the top of a grain silo dome. Guests were invited inside, asked to lie down, and, looking up, watched a mosaic of continually changing films and slides that were concurrently projected across the dome’s interior. VanDerBeek imagined a network of Movie-Dromes operating internationally, linked by satellite, presaging the internet.

Endless Possibilities

By the time VanDerBeek arrived at UMBC in 1975, he was already in the international limelight—a filmmaker whose works had won awards at festivals worldwide and who had received support from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Rockefeller Foundation. He had taught, lectured, or been in residence at Columbia University, MIT, the Walker Arts Center, the Smithsonian Institution, WGBH (Boston), NASA, and dozens of other institutions and had enjoyed a 1968 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Ever fascinated by the possibilities of emerging technologies, VanDerBeek had branched out from film to embrace videography and computer animation, which seemed to offer endless possibilities. (His early computer-generated films were produced at MIT and at Bell Labs, where he was in residence and assisted by computer art pioneer Ken Knowlton.) An exhibition of VanDerBeek’s work Machine Art: An Exhibit of “Inter-Graphics” was presented in UMBC’s Library Gallery in spring 1976.

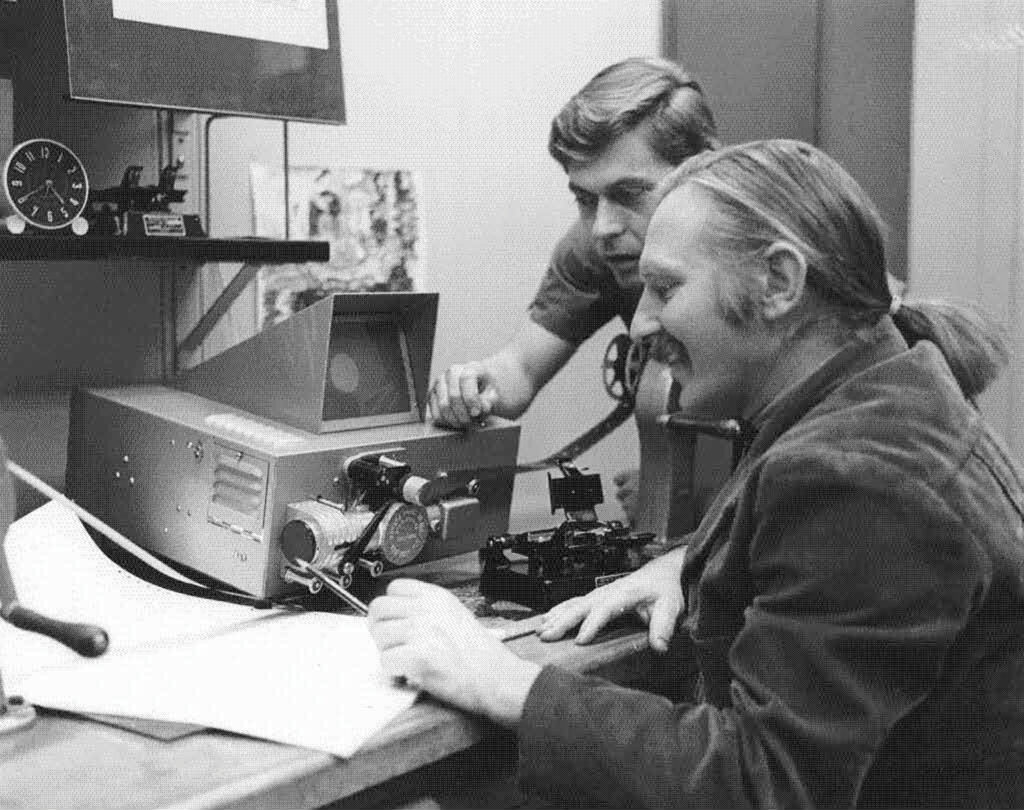

“It was a dynamic time,” remembers Ferdinand Maisel, who studied at UMBC and also worked in the dance department, “and Stan was maybe among the first interdisciplinary/collaborative artists of the 20th century. He was fascinated with how other people would think and solve problems. I met Stan via my work with Liz Walton—I worked for the dance department back then as a composer. Stan immediately had me push his shopping cart of films (which he was known to walk around campus) to a Steenbeck film machine, where I watched, with amazement, some of the films for which he wanted music.” VanDerBeek tapped Maisel to help run his Image Lab, a precursor to UMBC’s present-day Imaging Research Center.

While at UMBC, VanDerBeek recreated the Movie-Drome. Baltimore newscaster Denise Koch, who taught acting and theatre performance at UMBC, recalled, “Stan built a geodesic dome in the center of a large field and projected clouds and nighttime sky-lines, and had people come and lay on the floor for the experience.” (He had planned to erect on campus a 70-foot dome housing a 40-foot planetarium screen.)

Koch also stars in a 1979 VanDerBeek film, Mirrored Reason. “He came to me and told me he’d been given a studio at the Voice of America for a day, and wanted to play with some of the equipment and asked if I’d participate as his actor—how could I refuse! We went to the studio, and he placed me in a room and just asked me to do an improvisation. I think I used a Kafka story to fall into a state of paranoia as Stan fooled around with my image. At one point my head splits in two and then I’m facing myself—thus, I believe, Mirrored Reason. Stan and our theatre company, Kraken, collaborated a number of times. Once, he took video of each actor’s head in the exact same position and then had us bleeding or melting into and out of each other as if we were a company made up of one face that held the persona of eight different people. It’s hard to explain, but I remember I was stunned!”

Ellsworth Hall remembers that VanDerBeek’s “office was rather messy with stacks of magazines, books, and film cans, but he knew where everything was!” Always encouraging his students to branch out with novel techniques, “In Experimental Film class Stan would have us put objects directly on unexposed film and then move them and expose each frame so as to create a direct animation on the emulsion. Very unusual technique, but it resulted in some interesting images.”

Steve Estes, who studied film at UMBC as an undergraduate and then returned to earn an MFA in 1997, remembers VanDerBeek as an encouraging, supportive force. “He was very open, and very open to whatever you really wanted to do. Stan was the kind of guy who was helpful by basically just being there, and letting you do what you did, and providing whatever assistance he could. He had suggestions about this or that, but he was pretty much, ‘Go for it! Freedom, man, just go ahead and do it. Explore! Play!’”

Filmmaker Richard Chisolm ’82, interdisciplinary studies, recalls VanDerBeek as a character whose mind was sometimes racing so quickly that he wasn’t always focused on teaching, but says, “This dreamer personality, this charming dreamer, is kind of by definition boundary-less, and wild, and expressive. We need Stan VanDerBeeks to challenge our otherwise concrete, boring, structured way of looking at the arts. True art is extremely messy. It requires taking risks, and it requires trying things that are going to fail, and losing money, and losing time during those failures, and people like Stan are just fearless and have no regard for whether this dream is going to come true or be doable or not. It’s the old cliché about throwing things at the wall and seeing what sticks—that’s definitely how he looked at ideas. He got ideas every day, and every week, and he tried to contagiously get people to jump in with him, and sometimes they would. He was going super fast every day, always walking and talking fast and could never sit still.”

Dreaming at UMBC

VanDerBeek’s “dreamer” personality was, in fact, fascinated by dreams. He posted a note in a 1970s-era publication, Dreamworks, encouraging readers to send him brief written descriptions of their dreams, saying, “I am seeking this material for developing my ‘dream theater’ and for other futuristic dream-related media projects…. I am convinced that movies are the visual enactment of the dream state. I do not know how specific this function of pre-visualizing and making tangible the dream state is in our lives. But my own instincts move me further into experimenting with such illusory systems, such as freedom of metamorphosis to create ‘meta’ images that can approximate the geometry and forms of dreams.”

UMBC’s connections to the VanDerBeek family run deep. Two of his children—August and Max—studied briefly at UMBC, and his daughter Juliegraduated in 2003 with a degree in theatre. Max returned in the 1990s to teach for the Department of Music; his son, Clay, was a Linehan Artist Scholar who graduated in 2017 with a degree in theatre. Another of Stan’s daughters, artist Sara VanDerBeek, has exhibited and spoken at UMBC’s Center for Art, Design, and Visual Culture. Stan VanDerBeek’s second wife, Louise, graduated in 1976 with a degree in interdisciplinary studies and an arts emphasis and then returned to earn a master’s in 1995 in instructional development systems.

“If I had to draw a cartoon for The New Yorker that was about Stan VanDerBeek?” Richard Chisolm asks rhetorically. “It would be Stan VanDerBeek buys furniture at IKEA, and then you see him in a room with the boxes, and then in the next frame you would see something that didn’t look at all like furniture, and the instructions would be curled up in the corner, and what he built would be this anarchistic mound of panels and windows that was not at all what the IKEA people were telling you to build.”

VanDerBeek served as chair of UMBC’s Department of Visual Arts for only a short time in 1983 and 1984 before becoming ill. Several days before his death in September 1984, he received a poignant good-bye letter from fellow experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, who wrote, “I grow more sure of what we’ve done, and that someday…our works and lives will be fully known to the ears and minds of human beings….”

— Tom Moore

*****

To learn more about Stan VanDerBeek’s work, visit stanvanderbeek.com. An exhibition, VanDerBeek + VanDerBeek, which presents artwork by Stan VanDerBeek alongside work by Sara VanDerBeek, is on display at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center through January 4, 2020.

Thanks to Max VanDerBeek, August VanDerBeek, Chelsea Spengemann, the Stan VanDerBeek Archives, and Judy Taylor.

All images, including header, courtesy of the Estate of Stan VanDerBeek.

Tags: CAHSS, Fall 2019, visual arts