By Susan Thornton Hobby

Every time a coronavirus patient is released from St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx, a song plays over the loudspeaker: “St. Barnabas for All of Us.”

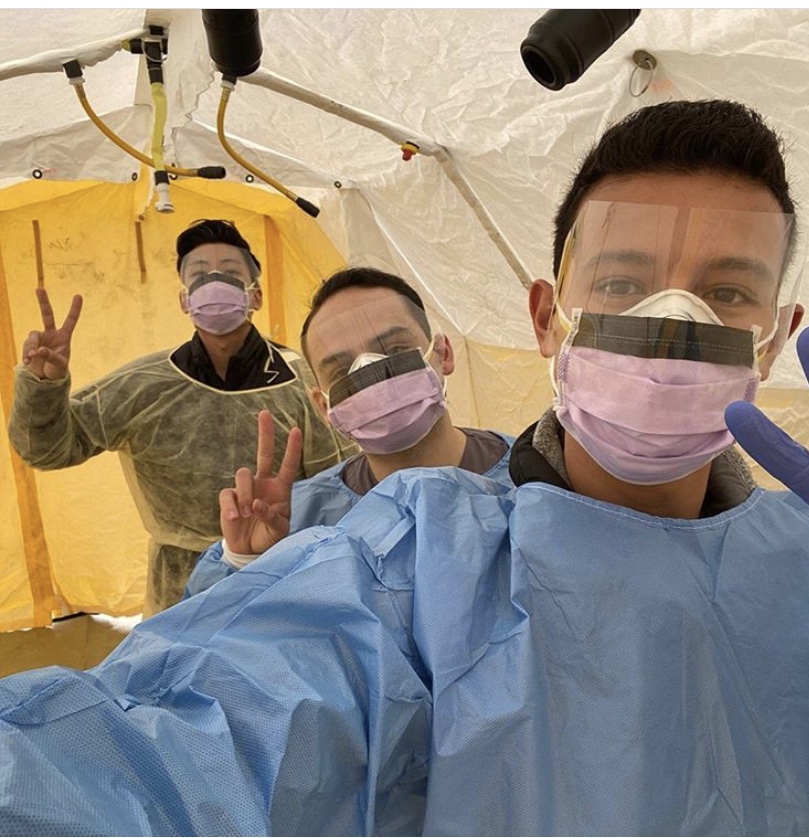

Trent Gabriel ’14, biochemistry and molecular biology, has heard the catchy tune several times, but not enough. Doctors call St. Barnabas a coronavirus “war zone,” with most of its clinics for specialties such as pediatrics and psychiatry now lined with bed after bed of patients with COVID-19. The hiss and click of ventilators fills the halls.

Gabriel is a dental resident who until mid-March handled routine and emergency dentistry at St. Barnabas. When the pandemic hit, Gabriel was pressed into service, filling in gaps when hospital staff were sick or overburdened. Among other jobs, he has tested doctors for coronavirus, taken vitals of COVID-19 patients, and filled prescriptions.

The pandemic necessitates fighting on all fronts. UMBC alumni and students are in the thick of that battle—testing hospital staff for the virus, screening patients at a Red Cross, riding in ambulances as an EMT, and many other roles.

Testing Medical Workers to Save Patients

When the pandemic closed St. Barnabas’ dental clinic, Gabriel was first assigned to test staff for coronavirus.

“It was really surprising how many had a good chance that they had COVID,” says Gabriel. “It hit the hospital really fast. These are doctors who know how to use PPE [personal protective equipment], and they’re getting sick.”

Several staff, including a trauma surgeon and two nurses who both were supposed to have retired but stayed at St. Barnabas to help, have died from the disease. Gabriel’s worry that he’ll become infected is ever-present.

“A lot of us have a fatalistic attitude,” Gabriel says. “We’re getting exposed every day. It’s going to happen. You just hope that it’s later, and we’ve figured out how to treat it.”

How to Train a Hero

“Many of our faculty, students, and staff are participating in an active role in the COVID-19 response, treating patients on the ambulance, in the field, in the emergency department, and providing consultation to direct response,” explains J. Lee Jenkins, chair of the Department of Emergency Health Services at UMBC.

To prepare for just this kind of health crisis, leaders in medical and traumatic emergency services serve as faculty members and mentors to provide practical experiences for the 80 undergraduate and 35 graduate students in the program, Jenkins says.

“While serving as an emergency physician, I’ve personally seen the toll that this virus has taken on our first responders, our nation’s emergency public health system, our patients, our students and faculty,” says Jenkins, who is an emergency medicine physician at Johns Hopkins Hospital and a faculty member in emergency medicine at JHU’s School of Medicine.

“Our nation’s emergency departments and EMS systems have been stretched past our limits in both physical and supply capacity as the front-liners bravely handle the physical and emotional needs of both themselves and the patients,” Jenkins shares. “Those in EMS and in the hospital continue to go to work, to take care of patients, then we come home to our families, each time worrying that we may have brought home this disease.”

Why engage in this risky profession? “We are here to serve, to go where we are needed,” adds Jenkins. “This is why our department, EHS, exists, to educate the next generation of these heroes.”

The Right Skills for a Crisis

Current EHS student Sanaz Taherzadeh says her life has prepared her for a pandemic. As a teenager, she watched her grandfather battle cancer in her native Iran and decided to become a nurse. After years working as an operating room nurse in Tehran, when a 2017 earthquake devastated the mountainous region of Kermanshah, Taherzadeh traveled there to triage and treat victims.

“I had to be brave, calm, and honest so that people could trust me and rely on me,” Taherzadeh remembers.

In 2019, Taherzadeh started her master’s in emergency health services concentrating in epidemiology at UMBC. For her graduate research, she has given presentations on personal protection equipment and coronavirus. All the threads of her knowledge—disaster medicine, epidemiology, and protective equipment—culminated when this coronavirus became a pandemic.

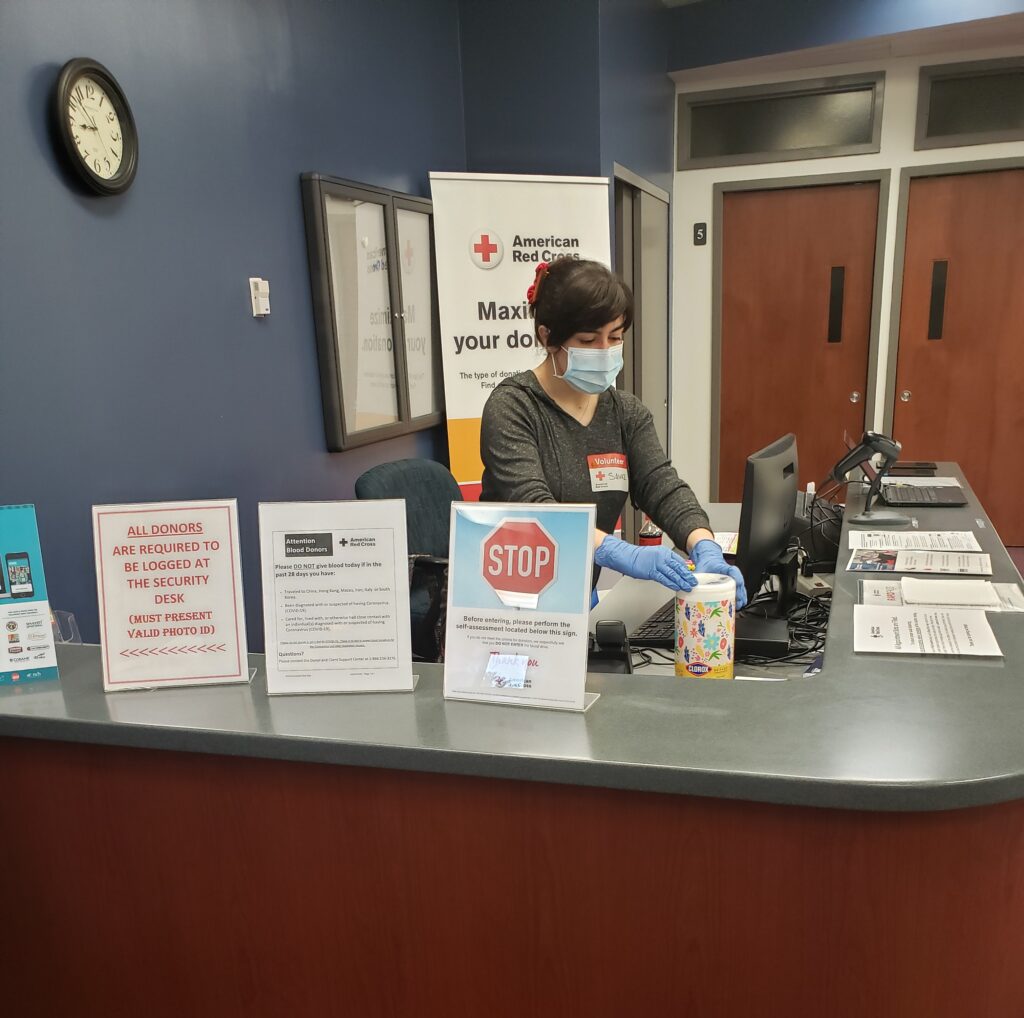

Taherzadeh, set to graduate in December, volunteers as a surgical support technician for the University of Maryland Shock Trauma Center, as well as for the Red Cross, where she assists victims at sites of disasters, and screens patients at blood donation centers to ensure they are healthy.

Even though Iran and the United States do not have a good diplomatic relationship, says Taherzadeh, and she worries about being deported, the nurse believes her place is here.

“Regardless of what our nationality is, what country we live in, or what religion we have, I believe we are human beings and now is the time that everyone in the world should work together to overcome this disease pandemic,” Taherzadeh says.

“Hard not to tear up”

Maggie Kemper ’14, biology, remembers her first patient with COVID-19. He arrived in mid-March, just after she and the rest of the nursing staff at Johns Hopkins Hospital had converted their Intensive Care Unit to an exclusively COVID-19 unit.

“He was pretty notable,” Kemper remembers, talking on an infrequent day off from her twelve-hour shifts at the hospital. “We had been hearing the patients would be older, immune-suppressed. But this guy was younger, a bodybuilder, no known health issues. It threw all of us for a loop. He was literally the opposite of what we’d been hearing. He was very sick, it was touch and go.”

But finally, the last week in April, the patient had recovered enough for staff to discharge him after weeks on a ventilator. The disease had transformed him. Kemper says, “he came in jacked, and now he’s very skinny.” He will likely need rehabilitative care, his lungs were severely damaged, and he can’t live alone for a while, she says.

“We gave him a standing ovation,” Kemper says. “It was hard not to tear up.”

Like all of emergency medicine, Kemper and her unit have been learning on the fly about COVID-19—how they must put patients on their bellies to help the blood and oxygen flow to their lungs, how they should try to have patients breathe on their own as long as they can without putting them on ventilators, how it’s hard to guess, now, which patients are going to recover, and which aren’t.

The disease is taking its toll on the staff as well. Kemper is working her usual shifts, plus overtime because the unit is usually full to its capacity of 24 patients, “the sickest of the sick,” she says. And because she shouldn’t remove her protective gear, which gives her rashes around her ears and neck, she goes long stretches without eating or drinking. And she worries about getting infected herself.

“Initially I was very scared,” Kemper said. “Now I’m too tired to be scared.”

But Kemper is also thinking about her patients, who can’t have visitors, and who are debilitated with the disease. So she started an art campaign. Kemper spread the word in her Hampden neighborhood, and to friends and family, to have people send in drawings and letters. Kemper then laminated the pieces so the art could be sterilized, and hung them all over the unit and in patients’ rooms.

“It’s so overwhelming,” Kemper said. “Kids are sending in drawings and letters that say ‘I love you,’ and they don’t even know these people.”

Be Prepared

First-year emergency services and theatre dual major Jack Bez is just beginning his studies at UMBC, but is already using his skills. For 18 months, Bez has worked as an EMT with the Gamber & Community Fire Company. When campus closed, the Eagle Scout chose to live at the firehouse instead of moving home, to avoid exposing his parents to the coronavirus.

Between responding to several ambulance calls a day, Bez is keeping up with his studies in theatre. He hung sleeping bags from a top bunk in the firehouse to fashion a sound booth in which he could record his sound production assignments.

Though Bez hasn’t yet treated a confirmed coronavirus patient, he has trained on prevention techniques and decontamination, and is activated with Maryland Medical Reserve Corps.

“All I know is that I’m content with being able to help people who need it, whether it’s COVID or not,” Bez says simply.

Looking Forward to “Normal”

When the pandemic crisis first began flooding hospitals with patients, but New York City hadn’t yet been put on lockdown, Gabriel remembers emerging from the subway after a long day of testing other doctors for coronavirus. Beside his subway stop was a public park, packed with kids and parents on a beautiful spring day. He remembers being afraid.

The pandemic, Gabriel says, “turns everything that makes us human on its head. Is it that bad to go to a park? We take for granted the things that keep us together.”

When Gabriel finishes his rotation at St. Barnabas this year, he’ll head to Boston University to complete specialty training and a program in crowns and dentures. He’ll be learning the aesthetics of making people’s smiles better, the layering of porcelains on implant teeth, full-mouth dentures on complex cases.

“Something calm and safe,” Gabriel says with a laugh. “Compared to now.”

Catherine Borg contributed to this story.

Header image courtesy of Jack Bez.

Tags: COVIDresearch, EHS, Resilience, UMBCTogether