It all starts with a seed—a source of hope.

Or in this particular case, a handful of seeds in the form of alumna Tamera Davis’ second grade students at Lakeland Elementary/Middle School. The class is fidgety but tuned in. As they jump into a rhyming exercise, Betsy Sherman joins them in a game of call and response at the front of the classroom.

A former teacher herself, Sherman feels right at home at Lakeland. In a hallway with cut-out paper letters reading “Education = Opportunity,” she smiles and waves to a line of students in puffy winter coats. As she sees kids studying in an alcove, she can’t help but peek over their shoulders in curiosity.

Earlier this winter, the Sherman Family Foundation donated $21 million to create the Betsy & George Sherman Center, which will expand and integrate UMBC’s work in teacher preparation, school partnerships, and applied research focused on early childhood education and improving learning outcomes for Baltimore students.

philanthropic relationships

for UMBC, Freeman and

Jackie Hrabowski have also

given more than $2.3 million

to the university over the

past three decades. Photo

by Jay Baker ’80, visual and

performing arts.

The gift—the largest in UMBC’s history—has the potential to transform both UMBC and generations of local students. The Lakeland partnership has clearly already transformed Sherman.

“You just never know how that one moment you spend with a child impacts their lives. You may never know,” says Sherman, who with her late husband, George, began partnering with UMBC in 2006 to create the Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars Program and other related initiatives. “And so you really need to be aware that your influence can be long lasting.”

Philanthropy of this sort is not about flash or money. It’s about the long game, driven by love and hope. UMBC has, for years, stood as a fertile planting ground for very personal, values-driven giving. It’s a vision shared by Freeman and Jackie Hrabowski and close UMBC partners who have connected over the idea that change is possible—and a belief in the promise one seed can hold.

Driven By Love

For Freeman and Jackie Hrabowski, the seeds of philanthropy were planted very early in childhood. He grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, the son of two teachers; she in rural Virginia, the daughter of two first-generation college students. Both recount stories of how their families helped their communities through work in schools and churches, and how that example stuck with them throughout their lives and careers.

“I think that my foundation for fundraising and philanthropy comes from the strong belief in the power of education to transform lives,” says Freeman, who has been known to sit on the floor with elementary school children to talk excitedly about math. “Jackie and I both understand, as the children of teachers, how important teachers were in our own development.”

Later in life, as Hrabowski matured into his role as president of UMBC, he and his wife became friends with George and Betsy Sherman—folks with similar interests and hopes. As their friendship grew, so did their vision of how they might change the face of education in Baltimore.

“As you build relationships, you build trust,” says Mrs. Hrabowski, who thinks of Betsy Sherman and her late husband as family. “You share lots of time together talking about your differences, your perspectives, and how to make it all work. It’s all about the realities of where we are and what we can do together to make a difference.”

Because “people tend to give to people,” as both Hrabowskis say, it’s not surprising that so many major philanthropic endeavors at UMBC have felt so personal in nature. Dr. Hrabowski’s relationship with Robert Meyerhoff—and a shared vision for making science more accessible to students of color—turned into a more than 30-year endeavor that has since changed the face of science and technology through the Meyerhoff Scholars Program.

“I threw the ball, but he ran for the touchdown,” Meyerhoff said of Hrabowski recently. “He made the most of it. He is a wonderful man.”

Similarly, a relationship with Earl and Darielle Linehan that began with Mr. Linehan’s serving on and chairing UMBC’s Board of Visitors revealed a deep desire to provide talented artists with an interdisciplinary approach to learning. Today, more than 300 Linehan Artists Scholar alumni are out in the world influencing dance, music, theatre, and other creative disciplines.

At the core of these partnerships—like so many others nurtured by Hrabowski—is a shared desire to help others thrive.

“When my parents and Jackie and Freeman get together, they talk about changing the world,” says Dave Sherman, noting his parents’ great love of Baltimore. “My mom and dad…not only would they provide resources, but they would provide passion. They would provide involvement…but it really all goes back to the people. And my parents wouldn’t support something that they didn’t believe would have the ability to grow.”

Watching It Grow

From her vantage point as a UMBC alumna, a mentee of Jackie Hrabowski, and vice president for economic development at Johns Hopkins University and Health System, Alicia Wilson ’04, political science, knows a good long-term investment when she sees it.

Wilson has felt the personal investment the Hrabowskis have made in her ever since she was a student. Recently, when she was sick, the pair brought Wilson a homemade pot of chicken soup, she says. At night. During a snowstorm.

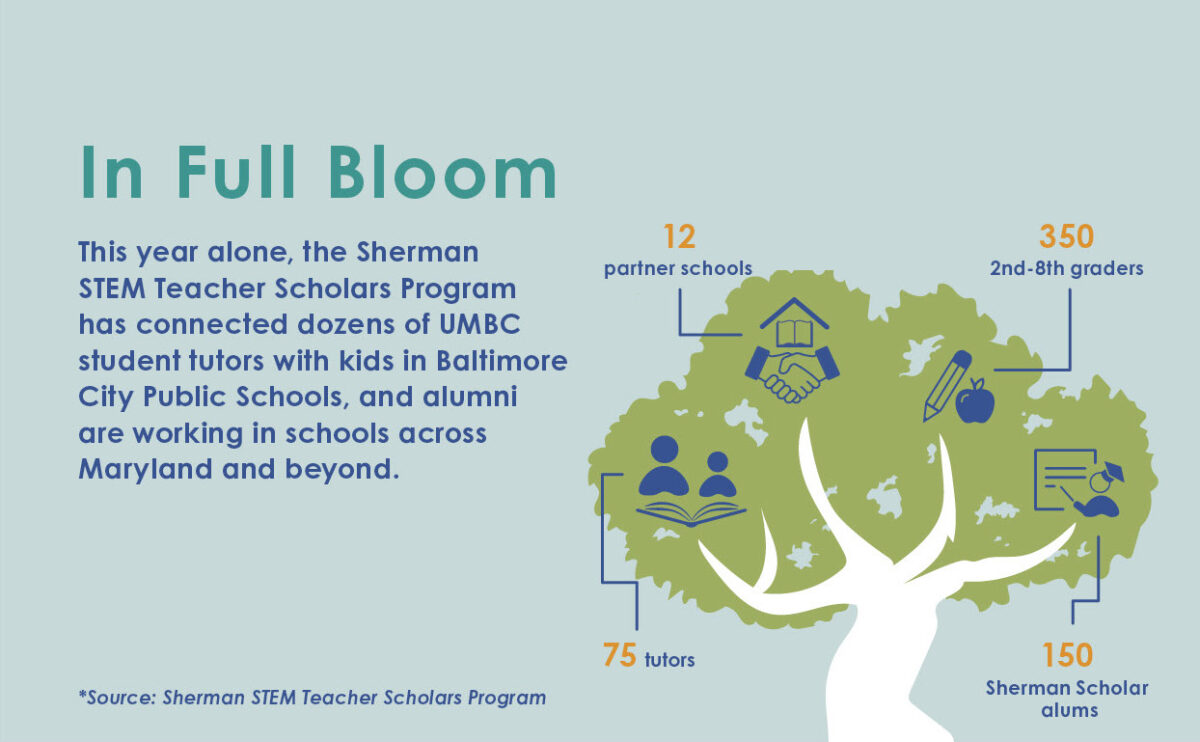

Beyond her own experiences, Wilson understands how personal philanthropic commitment shows up in the community—and what a lasting effect it can make, both structurally and emotionally, for all involved. A program like the Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars is able to put enthusiastic and well-equipped teachers in front of underserved students who will thrive with the extra attention. The effort adds up over time, creating a pipeline of opportunity for kids all over Baltimore.

“If you think about the ripple effect of your impact, it’s really through people and it’s through what we invest in,” says Wilson. “And so, as you think about the impact of the philanthropy that takes place at UMBC, you can point to so many scientific advances, public health, social advances that really started at a school in Catonsville. And really the testimony is in the people.”

For Sandra Evers-Manly, president of the Northrop Grumman Foundation and a partner in the work at Lakeland Elementary/Middle School, what sets these projects apart is the way UMBC engages at all levels, looking at the long-term potential of collaborative effort. “When we first began the discussion with Freeman about his vision for Lakeland and all of our UMBC partnerships, it was never about one element, it was always about the whole picture—the impact and results. In Lakeland’s case, what did the partnership mean to the school, students, teachers, parents, and the surrounding community,” says Evers-Manly.

“UMBC is a great neighbor,” she continues. “Some people will pick just one thing, like scholarships, and that’s it. But UMBC will say, ‘We’re going to work with families. We’re going to work with teachers. And, oh, by the way, we’re coming to you. You don’t have to come up the hill to UMBC. And we’ll find strategic partners to be a part of this.’ UMBC has the magnetism to help bring those key players into the room. What is equally impressive, is that you have both Freeman and Jackie who are so committed to the university, the greater community, and our nation. They do this in so many ways, both professionally and personally.”

The success of a partnership can be measured in many ways—and UMBC loves to measure and study regularly to make sure their programs are working. The Sherman Scholars program now partners with 10 schools to promote academic achievement through professional development for teachers and intensive tutoring for students. For example, more than 90 UMBC students, including Sherman Scholars and others, provide evidence-based math tutoring for over 350 elementary and middle school students in several schools across Baltimore. Early data show this approach is working.

But much of what drives these programs goes beyond data.

“This isn’t academic. . . It is a heart move,” says Wilson. “And thank God their hearts are pure and good and filled with love for young people. . . and the belief in the fact that young people, regardless of their background, can achieve.”

A Seed Sustained

When Hrabowski was still interim president of UMBC, then Maryland Governor William Donald Schaefer asked what he might do to support him and UMBC. Looking out over campus from the roof of the Administration Building, Hrabowski made what was probably an unexpected request.

“He…asked what he could do, noting that he didn’t have a lot of money to throw around. I said ‘Give me trees!’” Hrabowski writes in The Empowered University, noting that Schaefer quickly followed up by calling the Department of Natural Resources and having trees planted all over the young campus grounds.

Overnight, the campus was visually changed. Thirty years later, stands of mature trees provide sanctuary for wildlife and green space for all.

Thinking back on his years at UMBC, Hrabowski reminds us: “It’s not about me. It’s about us.” None of UMBC’s successes happen without the community, he emphasizes. UMBC is strong because we have put in the work, grown our endowment from practically nothing to more than $125 million, and proven ourselves year after year. UMBC will remain strong because of our shared commitment to inclusive excellence.

In his final months as president, Hrabowski has sealed his legacy yet again with the founding of a named scholarship that will increase access and affordability for undergraduate students with financial need and a commitment to community service. And while he has promised never to stop planting for UMBC, it’s up to the rest of us to nurture the trees he’s so faithfully tended.

“The seeds that he planted so long ago are now mighty trees,” says Wilson. “But, the goal isn’t that we just get to sit under the shade of the trees. We also have to go and plant some trees and build upon that legacy.”

Learn more about the Freeman A. Hrabowski, III, Endowment for Student Excellence at giving.umbc.edu/hrabowskifund.

Tags: giving, Lakeland Elementary, LinehanScholars, MeyerhoffScholars, Sherman Scholars