Today, millions of college students across the country are voting. Other students are not voting—they might be discouraged that their voice can make a difference, uninformed about their voting rights, or just unengaged with the political process.

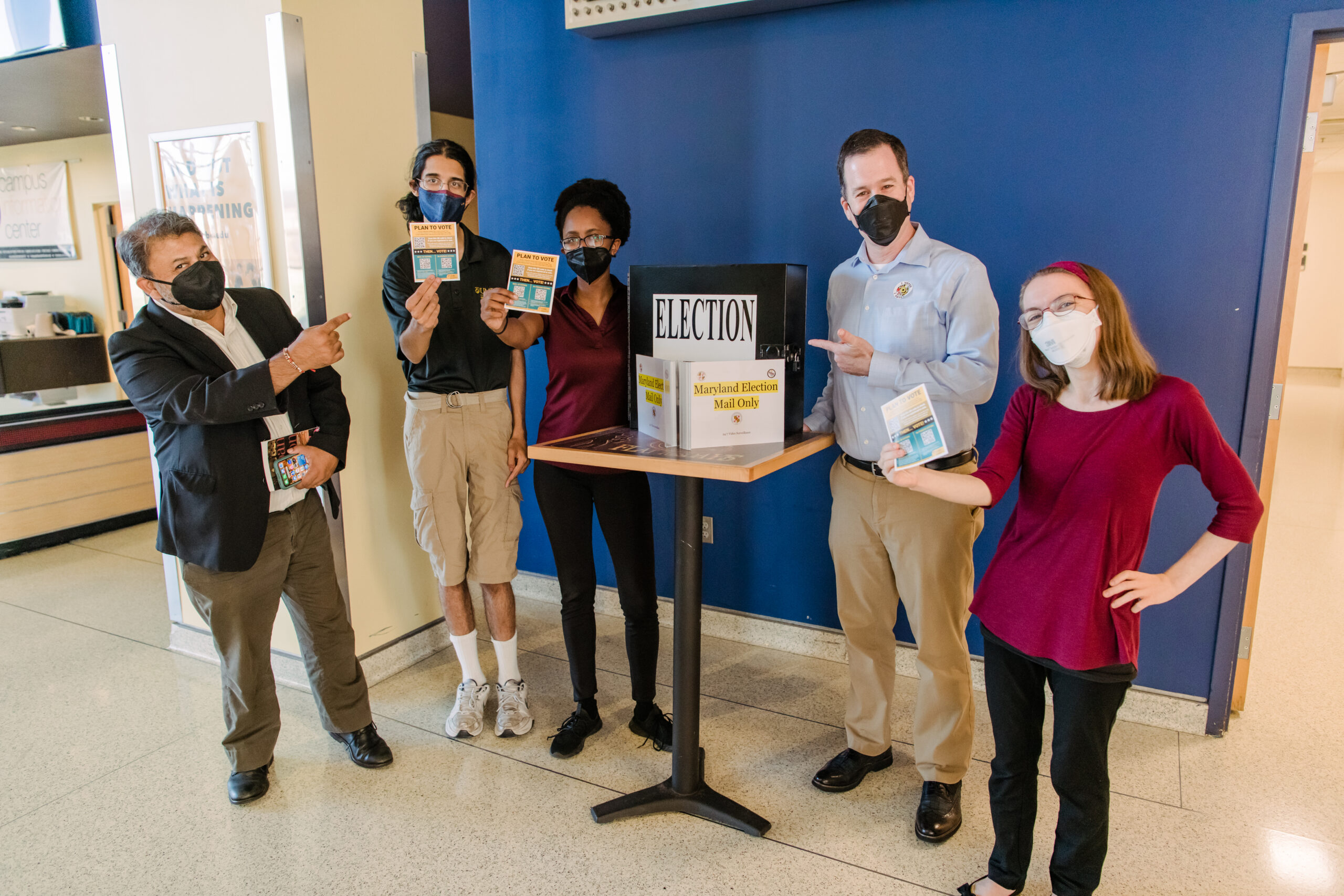

In a conversation facilitated by UMBC Magazine, Musa Jafri ’24, political science, SGA director of civic engagement, Sunil Dasgupta, professor of political science, and founder and host of the podcast “I Hate Politics,” and David Hoffman, Ph.D. ’13, language, literacy, and culture, the director of UMBC’s Center for Democracy and Civic Life, discuss the vital democratic process—on campus and off—and the daily practice of voting.

“Voting is about you taking a stand and stating, ‘I’m here, I matter, I exist, and I have a voice.’ It’s a form of resistance, a way to try to change the climate you find yourself in.” says Jafri, co-chair of the University System of Maryland Student Civic Leaders Committee.

“I don’t understand how democracy became compartmentalized to something that happens every four years. Voting is the culmination of the work that we have done for the past four years between the time we last voted and now,” says Dasgupta. “Voting is a moment of celebration. A moment where we find out whether the work we did in between votes really mattered. There is no other way to think about democracy. Voting is what we do every day.”

Dasgupta: From my way of thinking, a university campus can be very different than society at large. What is the difference and how does that manifest in civic life, on campus, and in communities? How do we navigate those differences?

Hoffman: In our broader culture, we speak too easily of universities as separate from the rest of society: as ivory towers where students are being prepared for the ‘real world.’ The reality is that universities are life. Students are alive right now and they are part of many communities within and beyond the university. What happens here matters to the lives of everyone at UMBC and the communities they are part of.

Jafri: I agree. There are many instances where the university and local community needs overlap. Recently, some UMBC students organized an event where we invited the Catonsville and Arbutus communities to meet the candidates in our district. By including these two communities we realized that we had similar concerns including education, clean water, and environmental protection.

Jafri: My generation is very politically active when it comes to voting and getting out to the polls. But with the plethora of social media platforms and news outlets how can students ensure they are getting valid and factual news?

Dasgupta: Let me be a professor and say there is more reading to be done. If your news derives from digital platforms, these platforms are algorithmic with a selection bias problem that is not your selection bias problem. You are essentially hostage to their selection bias. The way you have to overcome this is to move beyond one or two or even three sources of news. What all of us need to do is a triangulation between you and multiple sources. That takes work. Social media won’t replace in-person organizing or knocking on doors. On the other hand, organizing alone can be more effective with social media’s reach. The combination is necessary. At the risk of saying go do more work, I do think we have to understand that choosing one approach is not sufficient.

Hoffman: A part of what happens when you get involved in on-the-ground organizing is that you become better able to discern the plausibility of claims that you might encounter online. You become a better evaluator of the information you are receiving. One of the premises of Center for Democracy and Civic Life’s work is that democracy is not just a form of government, it’s not just politics and elections, it is a way of life that can be enacted in everyday settings. Ideally, people vote because they are so thoroughly engaged with the issues in their community and nation and understand them so well that voting is an obvious way to contribute. It’s one facet of how we shape our collective future, but far from the only one.

Jafri: One of the comments I often hear from students is that their one vote will not matter because it doesn’t determine the outcome. How can students and the broader community understand that voting is important even if their one vote may not be the deciding vote?

Hoffman: There are a lot of reasons to vote including enacting a symbolic and moral commitment to the well-being of your community. If your vote does not determine the outcome it will still be counted. Candidates and elected officials will review voting data to learn about who voted. In the elected official’s mind if a high percentage of young people voted then their concerns are important. This matters a lot.

Hoffman: What can communities do to help heal the deep divisions in our society that are evident all around us every day?

Jafri: I lean a lot on the power of storytelling—of meeting people where they are and hearing their stories. The divisions in the broader U.S. and in our communities come from a lack of understanding of someone else’s experience. Listening to another’s experience is very powerful and helps us see multiple realities. Maybe we can work together to address our concerns even if our approaches are different.

Dasgupta: I agree with Musa. Storytelling is very powerful and important especially when communities are in need of reliable news sources. I created my podcast to fill a gap in news coverage in Montgomery County. Providing a sound space where community leaders and elected officials can share their insights and plans for the future is one way I give back to the community, especially in areas where there isn’t a local newspaper.

Hoffman: What are some practical examples of things students can do that may not be obvious to them as opportunities for civic engagement?

Jafri: Some define democracy and civic engagement as just voting. I don’t think that is a fair description of democracy and civic engagement. Simple things such as gathering with friends and inviting someone who has different views than your own is a very basic way to be civically engaged. I think that can do a lot of good in helping heal the divide.

UMBC Magazine: What wisdom can you impart to inspire students to not give up and to show up and vote?

Dasgupta: The challenges are always going to remain. Our lives’ work is to work through these challenges with hope. We don’t have to solve everything but we are duty-bound to try solve some of the issues we face.

Hoffman: I believe that the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice but that achieving it in our lifetime requires constant organizing. I also believe that democracy is a journey, not a destination. We will never fully achieve the just society that we aspire to but we can get closer and closer and work together to prevent backsliding. I have seen a lot of positive changes in my lifetime including the expansion of rights and the recognition of people based on their identities. The backsliding we have experienced lately has not fully erased this progress so I have hope that together we can build a more just society and that in fact, the seeds of that society have already been planted.

Update: In late November 2022, the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge released the results of its national student voter pledge competition. UMBC finished at #4 in the nation in the number of students pledging to vote in Election 2022, moving our campus community up from #9 in 2020.

Tags: CAHSS, Center for Democracy and Civic Life, language literacy and culture, PoliticalScience, ShadyGrove