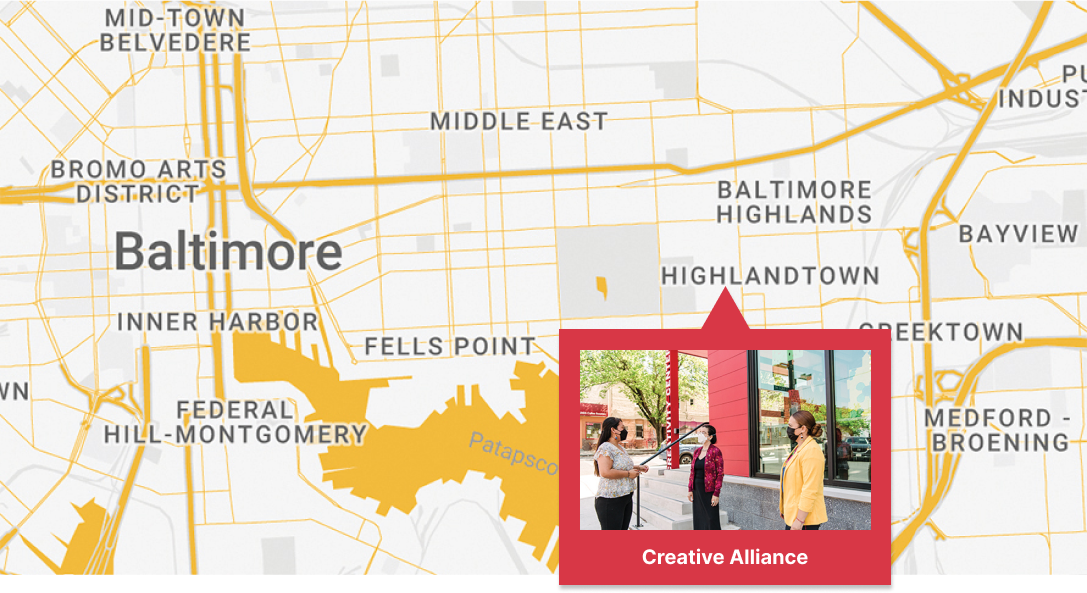

On a warm and bright sunny day in April when the trees in Baltimore City’s Patterson Park are changing from bright green buds to full leaf and the birds are competing with the car horns, Viridiana Colosio-Martinez ’22, modern languages, linguistics, and intercultural communication, and M.A. ’24, intercultural communication, waits in front of the Creative Alliance, a community and performance space a few blocks away from the park. After three years of undergraduate and graduate classes with her professor Tania Lizarazo, Colosio-Martinez is finally meeting her in person.

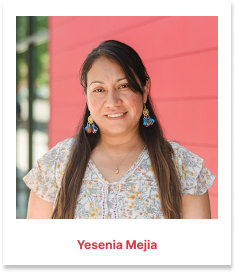

“I’m nervous and excited,” she says, waving to Lizarazo, associate professor of modern languages, linguistics and intercultural communication and global studies, as Lizarazo crosses the street to meet her and collaborator Yesenia Mejia, director of Creative Immigrant Educators of Latin American Origin (CIELO) and the Artesanas Latin American cultural enrichment program coordinator at the Creative Alliance.

“I can’t believe it’s the first time I’m seeing them outside of Webex,” says Colosio-Martinez.

There was a lot of hugging—the kind of hugging that is reserved for a friend you haven’t seen in years. Together, the group is gathering to review digital storytelling projects they’ve been working on together virtually for the past year, which they will present at the International Digital Storytelling Conference in Baltimore this summer.

Led by Lizarazo, and in collaboration with local Latin American communities, they are working to center the human experience by collecting and sharing a range of immigrant journeys that have previously been unrecognized.

“Lived experience is knowledge and should be part of knowledge production. A lot of our students are immigrants or their parents are immigrants and seeing experiences of migration beyond academic writing motivates them to explore their own personal and family stories,” says Lizarazo.

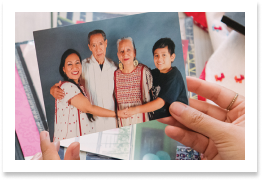

Tania Lizarazo, Viridiana Colosio-Martinez ’22, M.A. ’24, and Yesenia Mejia have been working together to tell the immigration stories of Baltimore’s Latin American communities.

Making teaching and research accessible

When Lizarazo moved from the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) to teach at UMBC in 2015, she felt an urgent need to create community. It had been easy to find a Latinx community in Davis but less so in Maryland.

“I arrived in Baltimore and suddenly I’m walking into places where I’m the only Latina. I don’t think that it’s healthy for anyone,” says Lizarazo. She began volunteering at the Creative Alliance where she met Mejia and started Latinas in Baltimore.

During the pandemic, Lizarazo, who is chronically ill and immunocompromised, has found that virtual classes and tools allow her to continue teaching and engaging in research with the community. In fact, the pandemic made accessibility that had previously been considered impossible the norm.

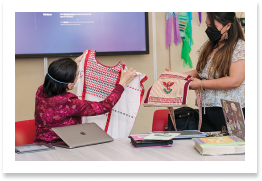

Mejia shares pieces of her family history, including a cotton huipil (tunic) hand embroidered with red and orange nahuales, and a family picture with her mother wearing it.

“We were so close to reimagining what community care could look like in 2020. We should not leave anyone behind or require people to choose between showing up or protecting themselves, their families, and their communities,” says Lizarazo.

“I am also committed to showing that we don’t have to choose between presence and safety. We can imagine collaborations that do not require additional exposures during an ongoing pandemic, that acknowledge that we have different access to resources such as healthcare, and that value interdependence and community care. Not only do I want to collaborate in producing knowledge but I want to be mindful of the context of these collaborations and not pick and choose what justice is when marginalized people keep being the most affected by the pandemic.”

Together with the Baltimore Field School, a part of UMBC’s overarching public humanities programming, and her partner researchers, Lizarazo has spent numerous hours building the relationships needed to help community members tell their stories.

“In the same way, community members rarely feel included in academia in different ways than research subjects. Creating opportunities for dialogues opens up opportunities to imagine new interactions and collaborations where not only the researcher’s knowledge is valued. Researchers would not be able to do anything without relationships and collaborations with students and community members.”

Slow research

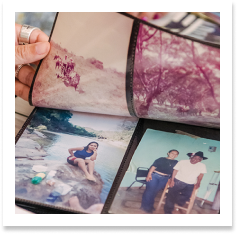

The researchers sit around a table and listen to Mejia describe photos of her family back in Santa María Zacatepec, Oaxaca, Mexico, during the 1990s. A faded photo shows her and her sister riding horses at a ranch. She picks up a picture of her father and pauses. “I didn’t get to see him.” Mejia has not been able to return to Mexico for almost 20 years, during which her father died. Colosio-Martinez and Lizarazo nod, understanding the pain and joy in between Baltimore and Oaxaca.

Mejia, a Baltimore Field School fellow, is working on a digital story, a story map, and website for her project on Representations of Indigenous Traditions from Latin America in Baltimore. She unfolds a calf-length, white cotton huipil (tunic) hand embroidered with red and orange nahuales and proudly shows a family picture with her mom wearing the same huipil.

“My mom always wears her huipil,” says Mejia. “Nahuales are spirit animals that are assigned to a baby according to the day they were born.” This spurs a lot of questions about the nahuales while she shows another hand-embroidered item, a bag with nahuales made by a fellow Indigenous Tacuate artist from Zacatepec.

This community-centered approach to research where students and community members are the knowledge creators is a key approach to Lizarazo’s community-engaged research on Latin American studies, transnational feminism using collaborative methods. It’s a shift away from the colonial-minded ethnography methods created by academics in the global north to research communities in the global south.

“We need to recognize that trust-building is a slow process,” says Lizarazo. “It’s based on reciprocity and it’s essential to meaningful communication and collaboration with communities.”

“Academia has historically excluded marginalized groups while extracting their knowledge. This extraction translates into personal gain for researchers but rarely benefits the communities that have been researched. As universities are not always reflections of the local communities where they are located, I have always been interested in learning from community members,” says Lizarazo. “I enjoy creating, collaborating on, and supporting projects that would not have an exclusively academic audience and won’t exist (only) behind paywalls. This is particularly important in public universities.”

Lizarazo calls this “slow research.” She had been practicing it in her home country of Colombia and at UC Davis as a doctoral student.

“Tania was an early proponent of experimenting with digital storytelling as a research method. Uncomfortable with academic ‘interventions’ into communities, she liked the idea of putting digital communication tools in the hands of vulnerable groups, like migrants, who might not otherwise have access to share their experiences in the public sphere,” shares Lizarazo’s mentor, Robert Irwin, director of the UC Davis Global Migration Center.

“She was an advocate for listening to and learning from migrants. Hers was an important voice in the research group that designed our first strategies for deploying this methodology.”

Listening and learning

“Mujeres Pacíficas” was Lizarazo’s first digital storytelling project in collaboration with Afro-Colombian women activists in the department of Chocó, in Western Colombia, who were also advocates for land rights and women’s rights. She met the group in 2008. “Women were doing the work alongside men for years but their work had gone unrecognized,” says Lizarazo.

One of the first shared stories, recorded after five years of community building, was created in collaboration with Luz Adonis Mena Becerra, a member of the Main Community Council of the Integral Peasant Association of the Atrato River, a Black farmers’ association in the Colombian Pacific, where Black communities were officially granted territorial rights in 1993.

“In the process of creating Luz Adonis’s story, I found out she had faced forced displacement and had lost everything she owned in a fire years later,” says Lizarazo. “Despite this, she reconstructed her memories through community photographs for her story.”

The project inspired Lizarazo’s forthcoming book from the University of Illinois Press, Postconflict Utopias: Performing Everyday Survival in the Colombian Pacific, a part of the “Dissident Feminisms” series. “The willingness to imagine these stories before they had audiences, and in spite of the absence of personal archives, is utopian,” says Lizarazo. “Not because these stories are ideal or unrealistic but because they invite the audience to imagine what seems impossible: the end of decades of violent conflict into a material reality.”

Student-teacher and the teacher-student

Parting with colonial-minded immigration research means developing new frameworks that humanize data and shift the process of gathering and disseminating information from one person to a community with a diverse and evolving set of skills and expertise.

“Equipping immigrants with the tools and methods to co-create personal stories can help us understand migration as a hemispheric experience in the context of globalization, colonialism, neoliberalism, genocide, and marginalization, especially of Black and Indigenous communities in Latin America,” says Lizarazo.

These voices highlight the multitude of paths immigrants take that are equally stories of joy, success, family, and community love as they are stories of survival, sacrifice, separation, and pain. There isn’t one Central American experience, Mexican American life, or Latin American journey. Before immigrants became people of color, Latinos, or minorities, they were Aymara, Taino, Mayan, Colombian, Mexican.

“It’s important to critically study the connections between local and global contexts of production and consumption of these stories,” says Lizarazo.

“It’s a more horizontal teaching-learning experience, where students, community members, and instructors are teaching and learning. The world is messy; when we listen to each other, we can do things that we didn’t know were possible before.”

One penny

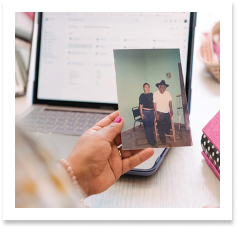

After Mejia places her photos and huipil on the table, Colosio-Martinez, research assistant for the Moving Stories: Latinas In Baltimore digital storytelling project led by Lizarazo, takes a deep breath and preempts the debut of her digital story draft by apologizing for the tears to come. A clip of a map shows a blue line tracing the miles of her life from Caborca, Sonora, Mexico, three hours from Phoenix, Arizona, to New Haven, Connecticut, to Baltimore.

A small picture of a penny appears on the screen.

“I’ll never forget when me and my mom tried to register for community college,” she begins, “but we were short one penny.” With each description, the penny gets bigger. “The registrar said she didn’t have a penny and shut the window in our faces.” The penny fills the screen. “My mom and I went outside and searched the floor until we found a penny.”

The pursuit of education is the connecting thread throughout the narrative. A photo of Colosio-Martinez wearing her cap and gown and celebrating with her husband after earning her associate’s degree is followed later by a screenshot of an email welcoming her to UMBC.

Colosio-Martinez covered her eyes to hide her tears. Lizarazo hugged her. Mejia touched her shoulder. They suggest she not cut her story.

Tags: Baltimore Field School, CAHSS, global studies, MLLI, public humanities, Research, Spring 2023