With their hearts in the work and their ears to the ground, the people behind some of UMBC’s longest-standing homegrown programs are solving big societal problems. But the work is never done.

By Jenny O’Grady

On the wall of the office, in bright Retriever gold, hangs UMBC’s vision statement, a bold call to action for any and all who happen to wander past. A call to “connect innovative teaching and learning, research across disciplines, and civic engagement.” A call to “advance knowledge, economic prosperity, and social justice.” No simple task, indeed.

There’s a quote from late Baltimore civic leader Walter Sondheim, as well. Christopher Steele keeps them here as a reminder that we’re all here to serve as well as learn. It can be messy work, he says, but worth the pursuit.

“Look at our vision statement. This notion of social justice and civic engagement are clearly stated…it’s in our values,” said Steele, Vice Provost, Division of Professional Studies, and Executive Director of the Shriver Center.

Founded in 1966, during a time of great civil unrest, UMBC is rooted in a type of service-learning that cuts across disciplines and traditional social structures. And the backbone of that work is programs like those of the Shriver Center, and many others homegrown on the UMBC campus, that over the last several decades have worked to address major societal problems of their time — from inclusivity in the workplace, to social justice in our cities — in collaboration with community partners.

Time passes, and successes come hard earned, because moving the needle takes both persistence and patience. Challenges change over time, forcing student learners and their instructors to bend and re-learn as they go.

The vision statement doesn’t precisely define the “why” of it all, but that’s not necessary. The answer is woven through everything these programs do.

Leveling the Playing Field

Imagine having a passion for technology or science, and the desire to make a difference with your talents. Now imagine encountering multiple locked doors before you as you attempt to enter the field of your choice — or even to pursue the study that drives you. Imagine hearing over and over again that this is “just the way it is,” or worse, the silence of no one noticing.

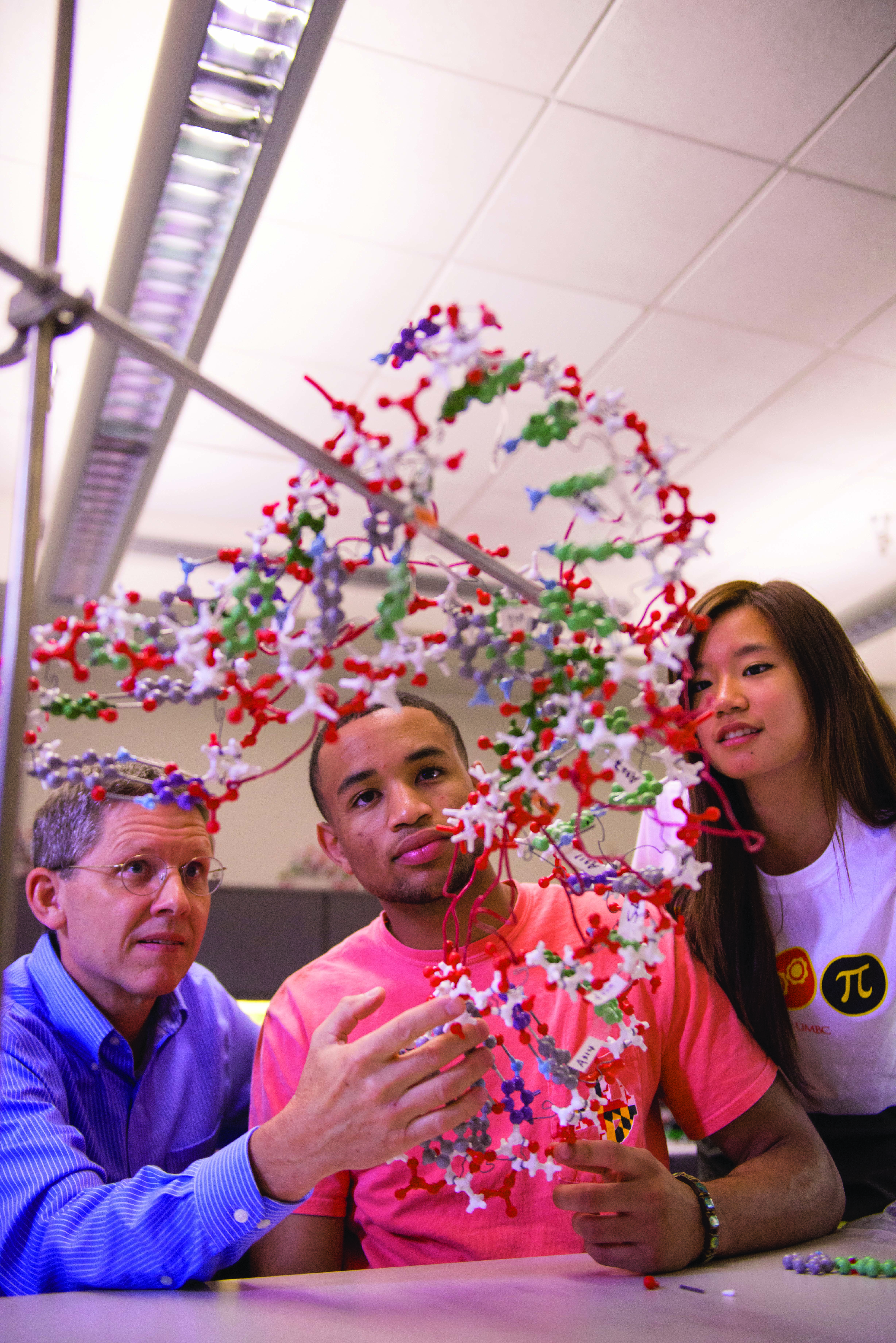

Decades after their founding, issues of accessibility in learning and industry still exist in the STEM fields. But, UMBC’s Meyerhoff Scholars Program and the Center for Women in Technology (CWIT) forge on, as they have for 30 and 20 years, respectively, working to open doors for underrepresented groups both as they learn, and as they move into the workforce.

“This is what drives us…increasing the number of women, and the participation of women, as well as other underrepresented groups in computing and engineering,” says Carolyn Seaman, associate professor of information systems and interim director for CWIT, not only because of the principal of fairness, but because the industry needs it.

“Better design requires a diverse set of perspectives, a diverse set of life experiences, a diverse set of requirements,” that can only be improved through diversification of these traditionally male dominated work spaces, she says.

As one of the nation’s leading sources of African Americans who get Ph.D.s in science and engineering, UMBC’s Meyerhoff Scholars Program does its work for similar reasons. Many academic doors haven’t traditionally been open to these students — not just at the college level, but far before that.

“There’s so much potential, and there are so many problems in the world. We need as many hands in the work as possible,” says Keith Harmon, director of the Meyerhoff program.

Both Meyerhoff and CWIT have evolved over time, as industry and societal needs revealed themselves. CWIT, for one, broadened its scope to include not just women, but male allies who could contribute to a shared vision. The program has also branched out to cover study areas that map directly to industry needs with the creation of its Cyber Scholars group, and worked to expand the program to students who need them most.

“We had people saying, ‘Well, you’re serving the best of the best, which is fantastic, but there are more than 3,000 other students in the [College of Engineering and IT]. How can you serve them?’” said Danyelle Ireland, associate director of CWIT. “We’ve done great things for our scholars, so there’s now more demand.”

Even if his program could double in size, however, Harmon believes that pushing the numbers too far could hurt the one-on-one attention his students receive, and, ultimately take away from the experience. Students in both programs graduate among tightly-knit groups who often refer to their cohorts as families.

T-SITE Scholar Kiante Brantley ’15, M.S. ’16, computer science, recalls a fellow CWIT Scholar found time to personally tutor him in a class he was struggling in even though he was working 20 hours a week with a full course load.

“Being a minority in STEM is hard, but you have a support system of other minority students, faculty, and alumni, then the struggle becomes easier,” says Brantley, now a Ph.D. student at College Park. “CWIT created a family that provided students like myself with the encouragement to make it through…tough times.”

For CWIT, the family means living on a residence hall together, eating together, doing Zumba together, and celebrating life’s victories. The same happens with the Meyerhoffs, where new students begin school the summer before fall semester — in a Summer Bridge program, an academic and social immersion that helps students quickly establish solid study habits — as cohorts that stick together long after graduation.

Rockford “Rocky” Foster ’13, mathematics, a member of the 21st Meyerhoff cohort who is nearing completion of a Ph.D. in mathematics at UC Berkeley, says he was embraced by the community immediately. Because of what he learned, he has started a “mini- Meyerhoff” system on the west coast, seeking out mentors and mentees as a solid support system. The Meyerhoff program’s “secret sauce,” he says, is the strength of those bonds; 30 years in, those bonds can be found across the country.

“So now, when a Meyerhoff undergrad is facing a challenge, chances are there’s a Meyerhoff who can empathize and provide guidance. When they identify an institution or professor they want to work with, there’s someone who can put them in touch or put in a good word,” says Foster.

“The truth is there are many people who are born with such networks in place; their families have accumulated a sort of academic wealth. But other people, historically disadvantaged people, have been denied the ability to accumulate this wealth. The incredible thing about Meyerhoff is that they built it in less than thirty years.”

As a Cyber Scholar, Priyanka Ranade ‘18, information systems, participated on an all-woman team in a cyber engineering competition sponsored by Northrop Grumman. The team won first place, and today Ranade works at Northrop as a cyber software engineer and serves as a mentor to a current Cyber Scholar team.

“We are not taught to solely invest in our own dreams,” she said, but “to use our strengths in helping others in their journeys, too.”

Filling a Teaching Need

Studies show that students in high-needs schools who are taught by teachers who come from similar backgrounds — and who can understand their specific needs and challenges — are more likely to succeed. And yet, filling those teaching spots presents a perpetual challenge, because teaching in those areas often carries stigmas that scare away potential candidates.

“The biggest challenges, we find, is just finding enough students who want to be teachers, whose families support that career path, and who want to teach in Baltimore,” said Rehana Shafi, director of the Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars Program, which for the past decade has worked to fulfill the mission of “for every Baltimore student an exceptional STEM educator.”

Today, the program has more than 90 alumni teaching and leading in schools all over the state, including in Baltimore city and Baltimore County, and 64 current students. Getting students interested in the first place may be difficult, but the program works to help them understand why this is such a special — and important — calling.

“We’ve shifted how we talk about teaching,” said Shafi. “We talk about social justice and equity. STEM is an integral part of our mission, but at the end of the day, we want people who are approaching teaching from those two lenses…especially when you’re working with kids — and with families and communities — who are the most underresourced.”

Knowing the challenges their students are facing as they student teach, the Sherman program in the last few years made shifts to offer higher levels of support, with the addition of staff who offer dedicated professional coaching for students. It also targets recruitment efforts in city schools because people often want to return to their home community to teach. And the program now requires annual applied learning experiences (an increase) in city schools or with programs that support kids from city schools.

This includes major work at Lakeland Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore city, where for the last six years the Sherman program has partnered on teacher professional development with math teachers, afterschool enrichment programs, and (along with elbow grease from the UMBC Peaceworker Fellows Program and financial support from the Northrop Grumman Foundation) the launch of a new Lakeland Community and STEAM Center.

Elizabeth “Rosie” Plitt ’14, psychology, M.A.T. ’16, education, who is in her second year of teaching kindergarten at Lakeland currently, says the professional coaching specifically regarding community and cultural responsiveness she received through Sherman is what sets the program apart.

“The program has opened my eyes to my passion for teaching in urban schools,” she said. “The community, the connection, and the reward outweigh the many challenging aspects that occur throughout the year.”

Joseph Skowronski ’18, biochemistry and molecular biology, joined Sherman “on a whim,” he said, “but it was a decision that I will be proud of for the rest of my life. I knew immediately that I was in the company of dedicated professionals who wanted nothing more than for each and every one of us to succeed and be the best teachers we could be.”

Currently completing both his master’s of arts in teaching and a year-long student teaching internship at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, Skowronski said he “loves walking into a class and seeing a fellow Sherman in the room. An instant connection is made in that moment, and I have a friend and partner in the class on day one.”

For Shafi, though pushing the numbers of students working in high-need schools is a goal, the real mark of success is a shift in thinking among them.

“We really want our students to deeply understand who they are and what they walk into the room with, and who their students are. That takes time,” said Shafi. “And then, when people ask, ‘What do you teach?’ that the first thing they say is ‘I teach students.’ It might be math. It might be chemistry. It be elementary, but ‘I teach students.’”

A Community That Cares

Dealing directly with critical social challenges can be messy, but for the past 25 years the Shriver Center has moved and changed to keep up with the challenge, connecting thousands of students and faculty to partner with people and communities to address their needs. Alongside them, the Sondheim Public Affairs Scholars have also contributed to service-learning, internships, activism, and research to enact social change since 1999.

Named in honor of Eunice Kennedy Shriver and Sargent Shriver with the mission of “addressing critical social challenges by bridging campus and community through engaged scholarship and applied learning,” UMBC’s Shriver Center serves as an umbrella organization with numerous spokes and broadly sweeping goals. The center runs programs covering everything from service-learning and community engagement (including the Shriver Living Learning Community, and service and leadership scholarships) and Public Service Scholars programs for students, to orchestrating engaged scholarship by faculty, to advocacy, academic support, and work experience for youth offered by the Choice Program, and intense community engagement via the Shriver Peaceworker Program.

“We’re trying to move toward social justice and increased equity across the board in society,” through approaches that involve students, faculty and communities, said Shriver Director Michele Wolff ’89, sociology.

“On the student side, we want to create spaces in which they feel empowered to become change agents to tackle issues identified by the community…and with faculty, we want to collaborate to connect their research and creative work with community-based activity. And then, we work directly with the community to help them address their identified needs, usually with students as the resource that helps build their capacity to lead positive change.”

Studies by members of the Shriver staff have shown that in addition to helping surrounding communities, applied learning of this sort also improves GPAs and graduation rates among participating students, while nurturing skills in leadership, public speaking, personal growth, and career exploration.

The center’s Choice Program offers community-based case management services and aims to foster healthy development and resiliency among youth from under resourced schools and communities. It served nearly 1,000 youth and their families in 2017, resulting in lower recidivism rates and a reduction in out of home placements.

When she came to UMBC, MaryBeth Hyland ’06, social work, wanted to become an orthodontist. But, her experiences working as a site coordinator with the Choice Program and living in the Shriver Living Learning Community put her on track for an entirely different career. In one case, she helped a youth with serious dental issues get pro-bono treatment with an orthodontist with whom she had previously interned.

“It was in that experience that I realized that I wanted to help people to get the support they needed to live better lives,” said Hyland. Today she runs SparkVision, an organization that helps individuals and companies to live in alignment with their values. “And I changed my major to social work and began to thrive.”

Many Shriver alumni maintain their connections long after they graduate. Peaceworker alumna Katie Long, M.A. ’10, intercultural communication, who currently works as program director and Hispanic liaison for the Friends of Patterson Park in Baltimore, still calls upon her Peaceworker family for support and camaraderie.

“I think the practical idealism that is instilled by the Peaceworker Program is much of the reason why many of us are able to continue with the fight for social justice and betterment of our city,” she said.

Service is also a core value of the Sondheim Public Affairs Scholars, who often collaborate with Shriver Center programs. By working closely on problems like poverty, inadequate education, or services for immigrants or disabled people, students broaden their horizons, build empathy, and become exposed to people they might not otherwise, says Laura Hussey, director of the program and associate professor of political science.

“When students learn about problems through direct encounters with the people they affect most keenly, the problems start to look a little different, and perhaps also more complex, than they might have looked from a set of statistics or ideological arguments,” says Hussey. “It’s a great learning exercise to balance and weigh these types of evidence — what students witness at their service sites, what they read in their textbooks, what they hear in the news or from their favorite political sources.”

During his years as a Sondheim Scholar, Evan Leiter-Mason ’17, economics and political science, started a student-run volunteer tax service for people in need of assistance. Today, he continues that work via the CASH Campaign of Maryland, driven by a desire to create a world free from poverty and financial hardship.

“The Sondheim program affirmed my existing desire to be involved in public service by connecting it to the legacy of Walter Sondheim and his work to make Baltimore a better place to live for its citizens,” said Leiter-Mason, who said he found mentors and friends who share his values and drive to help. “I believe we all have a responsibility, in our own way, to imagine and work toward a better world than the one we have.”

Tags: CWIT, Fall 2018, meyerhoff, mhoff, Sherman, Shriver, Sondheim