Assigned an oral history project in 2007 for her master’s degree in community arts at Maryland Institute College of Art, Ashley Minner—now professor of the practice and folklorist in the Department of American Studies at UMBC—knew exactly who she would ask to interview. She walked across the street from her parents’ house and knocked on Uncle John’s door.

“There will never be a person like Uncle John,” says Minner, an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. “I don’t know, he was just like that, always telling stories. He was a character. When he was younger, he had pork chop sideburns. He had a really thick Robeson County accent. He was a good man. I believe he was touched by God, he was—he is—a Lumbee Legend.”

Sharing their heritage with Baltimore

John Walker, if not a direct relative of Minner’s, played that role, telling her about their shared heritage and regaling her with stories of his youth in North Carolina, where many Lumbees moved from in the 1950s and ’60s to Baltimore in search of work. Minner’s subsequent research has helped tell the wider story of Lumbee migration to Baltimore, specifically to the neighborhoods of Upper Fells Point and Washington Hill, affectionately called “The Reservation.”

The original oral history project turned into a thesis of five artist books—which include transcriptions of five elders’ stories along with compiled photographs. This project grew into an exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Industry in 2011 that featured five additional oral histories and cultural artifacts. It felt like the project could keep snowballing, says Minner. It was around this time, she noticed that more often the oral histories were being used at elders’ funerals.

“They became more precious after that,” she says, as the growing awareness of losing a generation began to sink in.

In fall 2019, Minner met with staff in UMBC Special Collections to discuss the creation of a home for her work and other Baltimore Lumbee related research and ephemera. To be housed in the Maryland Folklife Archives, Minner’s recordings will become part of “The Ashley Minner Collection,” along with other documents and photographs shared by tribal members.

Preserving people’s stories

“This collection really demonstrates how the University connects with the surrounding community in Baltimore,” says Beth Saunders, curator and head of UMBC’s Special Collections and Gallery. “In other words, we benefit from stronger ties to the community we serve. Ashley really dug into local archives and did the legwork and other researchers will be able to benefit from that.”

Minner sees the archive as a necessary repository for stories and photographs, that otherwise might be lost as the Lumbees who previously lived and worked close together spread out into the counties surrounding Baltimore. “Ashley has a real, practical sense of the value of archives for preserving history and people’s stories,” says Saunders. “This new collection is an opportunity to preserve a part of that history that has been neglected and that she is bringing to broader awareness.”

Minner hopes the creation of the archive will encourage more Lumbees to dig into their past, while also finding pride in their present. ”We are made to feel as if we don’t belong on this landscape,” says Minner. “Many of our young people don’t know their history because frankly…their parents don’t know the history.”

“I think being able to point and explain and show pictures and ground them in the fact that our people have been here for close to a 100 years now and have really made contributions, that does something. That helps with security, self-esteem, and feeling empowered—like you do belong, like nobody lied to you. You are who you are.”

Ethics of community research

Minner bridges multiple spheres with her work—she’s an artist, a scholar, and also a granddaughter, a friend, a fellow tribal member. The only hat she can take off, as she puts it, is her UMBC hat. Otherwise, “what I’m doing and what I’m about is bigger than a job,” says Minner, “bigger than a job title or discipline.”

Part of having her feet in two worlds is training students how to develop holistic approaches to public scholarship and community collaboration. In Fall 2019, Minner was hired as the director of UMBC’s new public humanities minor. “We’re lifting up stories that get pushed to the margins,” says Minner. “And we spend a lot of time on ethics. The last thing I want to do is turn a bunch of college students loose on communities that might be harmed through the interaction.”

Minner is uniquely suited to the directorship, says Nicole King, associate professor and chair of the Department of American Studies. “Her broad range of experiences and skills, speaks to the many positions we all hold in our everyday lives. These human aspects are often flattened in an institutional context. Yet, Ashley is more than all of these credentials and roles because her practice focuses on seeing the humanity and beauty of everyday people and places. What Ashley offers to our students at UMBC is lived experiences that are both ordinary and extraordinary and an understanding of the connections between the two.”

From this perspective, Minner can see how outsiders often miss the mark when trying to tell the Baltimore Lumbee story. “They latch on to urban renewal and displacement,” explains Minner, “but the elders don’t see it that way. They’re not victims, that’s not the story they want to tell. It’s important to teach folks to listen deeply and to check in and make sure people are being represented the way they want to be represented.”

A memorable occasion

Minner has a story, one of her own that’s stuck with her as she’s watched her research expand through a process she describes as “pretty serendipitous.” Aunt Jeanette Walker Jones, Uncle John’s widow, says Minner, was instrumental in connecting Minner to her heritage. When Minner and her best friend, Nicole—Aunt Jeanette’s granddaughter—were 4 or 5 years old, she took them to have ribbon dresses made.

The fabric for the dresses was light pink with teepees on it and the ribbons adorning it were white, black, and hot pink, remembers Minner. They attended an event at the former Festival Hall downtown—an annual pow wow put on by the Baltimore American Indian Center. “We were out there hopping around; we didn’t know what we were doing. Some Indian guy looked at my mom, and when she nodded at him, he scooped me up and held my hand while I danced with him. I was like ‘ahhhh,’” she says, making an excitedly terrified face. “It was a thrill!”

******

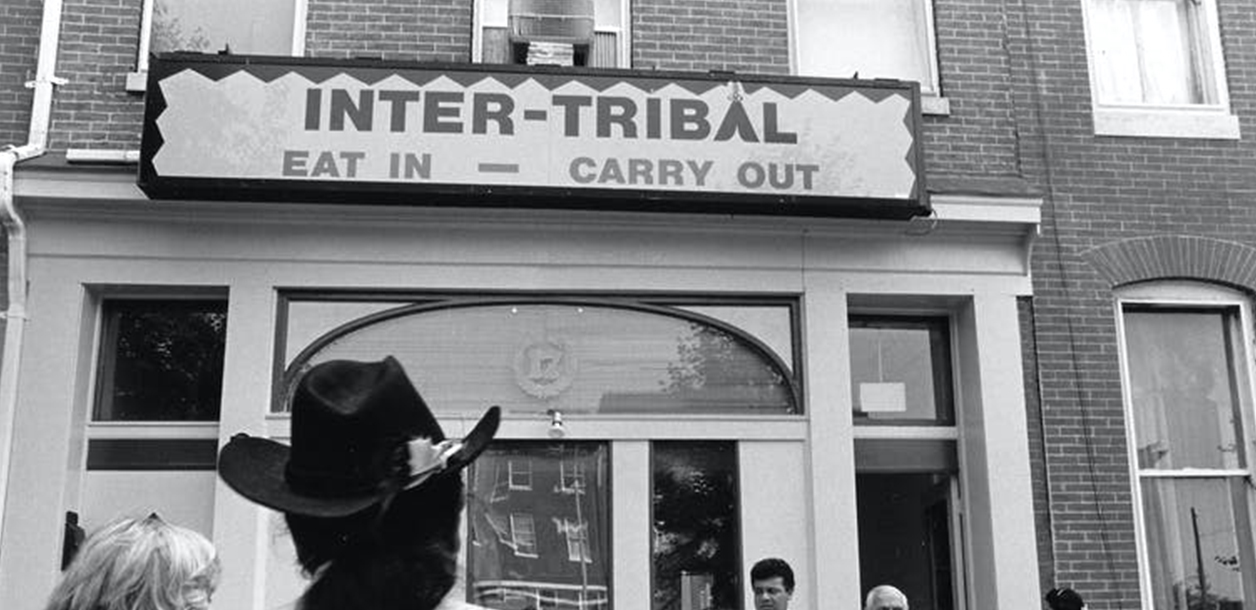

Header image: The Inter-Tribal Restaurant was owned and operated by the Baltimore American Indian Center in the unit block of South Broadway. Photo courtesy of the Baltimore American Indian Center, provided by Minner.

Tags: American studies, CAHSS, Fall 2020, professorsnottomiss, public humanities