Sonya Squires-Caesar, a doctoral candidate in UMBC’s language, literacy, and culture program, has been interviewing communities who use susus to save money for big-ticket items like homes, farms, or everyday needs like transportation and bills. Susu, a word thought to come linguistically from West African languages, is an informal structure of communal savings where individuals agree to give an equal amount of money to one pool. Members then decide the frequency of when someone receives the entire amount.

“I remember my mother planning her spending around when she would get her payment,” says Squires-Caesar, whose family is from Barbados. Squires-Caesar explains that susus—or rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs)—can be a way for people to access larger sums of money without the barriers formal banks and finance systems pose to people without high levels of disposable income.

“While there is a significant body of ROSCA research, it tends to focus on groups living in poverty or with minimal or no access to formal financial instruments,” says Squires-Caesar. “My study differs by focusing on middle-class and upper-middle-class immigrants who opt to use this informal, unregulated financial tool in the U.S. alongside mainstream financial services such as banks, credit cards, investments, etc.”

Squires-Caesar, the Dresher Center for the Humanities’ graduate student research fellow for fall 2023, is interested in studying the evolution of susus from the transatlantic slave trade to today. She explains that for centuries people have pooled their resources for individual and communal needs.

Honoring African indigenous knowledge

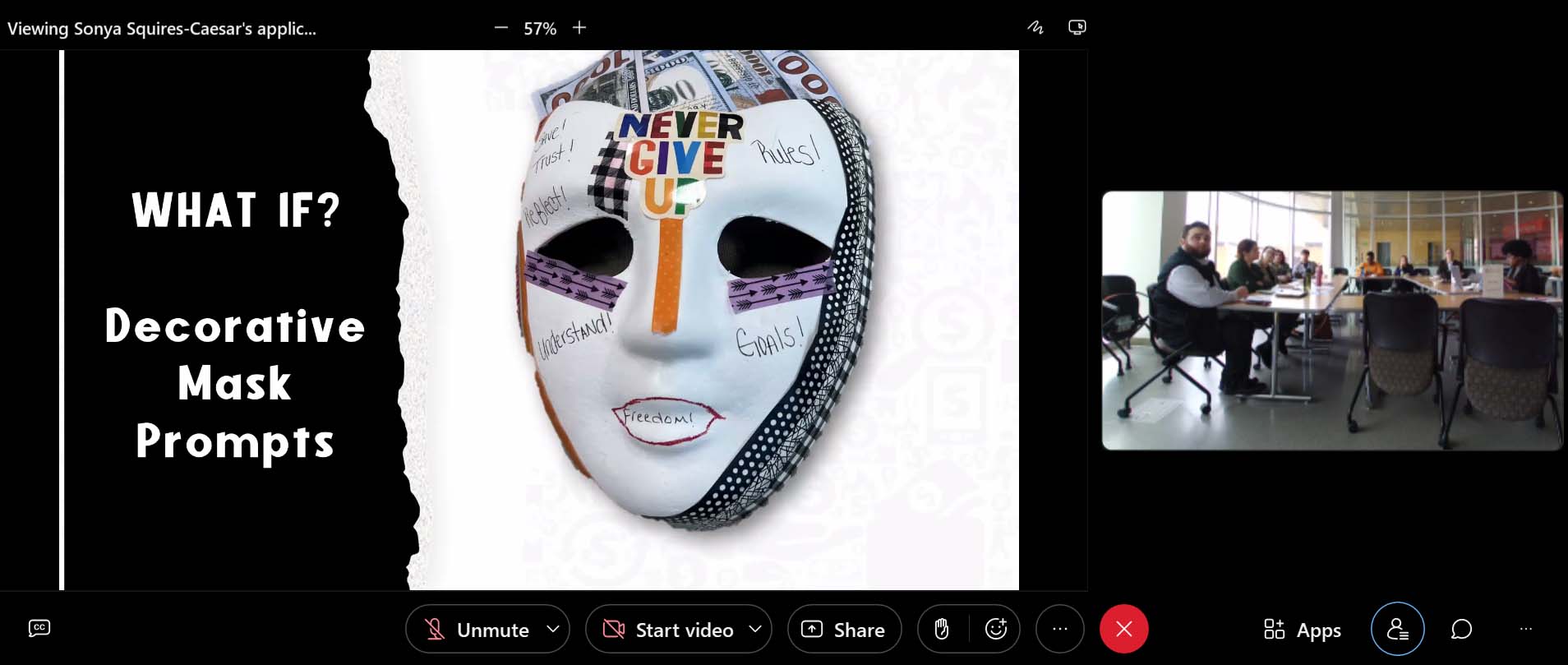

Susus are a cultural practice rooted in African indigenous knowledge, a term for how various African cultures orally passed a range of information, customs, and beliefs from generation to generation. “In African indigenous knowledge, the act of learning is thought to be a fully engaged journey to ‘find one’s face,’” says Squires-Caesar, “which is considered the path to discovering your roots, revealing your spirit, and determining the ‘fire in your belly’ or core elements that matter most to you.”

Squires-Caesar “found her face” when she aligned her research path with her authentic identity. “Western research methods couldn’t guide mine. I felt I was trying to fit a square peg into a circle,” explains Squires-Caesar. “I found my face when I realized the methodology that my project needed had to model the community I was looking to understand.”

Researching what’s below the surface

Squires-Caesar’s approach to understanding financial literacy is less about the stock market and credit and more about what is intangible. She calls it the iceberg effect.

“On top of the iceberg are tangible things like bank accounts and credit cards,” explains Squires-Caesar. “You can see, touch, feel, and measure them, but beneath the iceberg are the processes that may not have official rules and regulations and where the general public may not know they are happening, like susus.”

During the four years she managed a community college financial literacy program, Squires-Caesar met many students surviving from month to month. Through ethnographic research, she found students were using non-traditional ways to make ends meet, like getting cash advances from bingo halls to pay for bills and groceries. The data also showed that some students were overwhelmed by the idea of saving.

To shift that thinking, she created a microsavings project for her students to take them through the process of saving—a few cents here, a few dollars there, which grows over time.

These stories about the complexities of susu communities have inspired Squires- Caesar, as part of her Dresher Fellowship, to decorate physical masks as three-dimensional representations of financial identity, of “finding face.”

Tags: CAHSS, Discovery, Dresher Center, Fall 2023, LLC