In a recent essay, UMBC President Freeman Hrabowski notes, “In difficult times, we come to know who we are.” Never has that been more true than this year or at this point in our nation’s history.

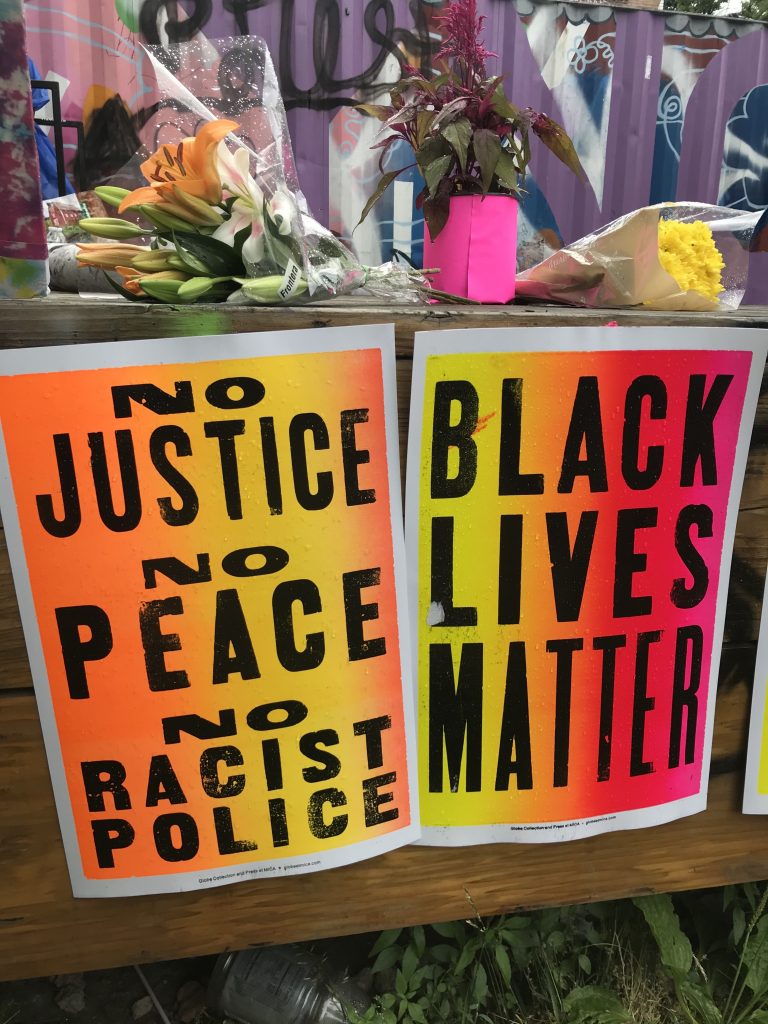

With the killing of George Floyd and other instances of police violence and the wave of protests that followed this spring and summer, many in our Retriever community are hearing the call to question what got us to this point and do everything they can to dismantle structural racism in our country.

In so many powerful ways, their voices echo those of some of our earliest Retriever alumni, who staged sit-ins on campus to protest the Vietnam war and civil rights injustices. In the spirit of this moment, many in our community are still protesting—but also taking to social media and finding new ways to make change from within their workplaces.

It’s difficult, but necessary, work. The moment is calling for an answer, and our Retrievers are responding. Because this is who we are.

THE LONG GAME

For several decades, Diane Bell-McKoy ’73, sociology and social work, has worked to make African American individuals and families in need become economically self-sufficient and to infuse philanthropic organizations with policies that create positive outcomes for people of color. UMBC Magazine talked with Bell-McKoy, CEO of Associated Black Charities and the Greater Baltimore Committee’s 2020 Regional Visionary awardee, about why making long-term change takes both patience and perseverance but is always worth it.

UMBC Magazine: What are you trying to achieve through your work with philanthropic organizations, public policy makers, employers, trainers, and educators?

Bell-McKoy: Our goal is to shift the lens to provide the facts, the history, and the current policies to let people begin to really see how we ended up where we are today. Because it was very intentional—and going forward we can make different decisions to change the outcomes and the workforce ecosystem as it relates to systemic racism as a root barrier. When Black and brown people have the opportunity to move up, the greater economic opportunity means that they can also buy a house, they can start a business, and they can contribute a great deal more to their families and to the economy.

So my days are always around educating, around influencing, around advocating, around sharing our policy….It’s about meeting with our fellow philanthropists, helping them see the world differently and then giving them the desire to go deeper into those policies, their practice, and their culture.

UMBC Magazine: Your organization’s “10 Essential Questions” guide really forces folks to look at their operations through an equity lens. Is this as eye-opening as it sounds?

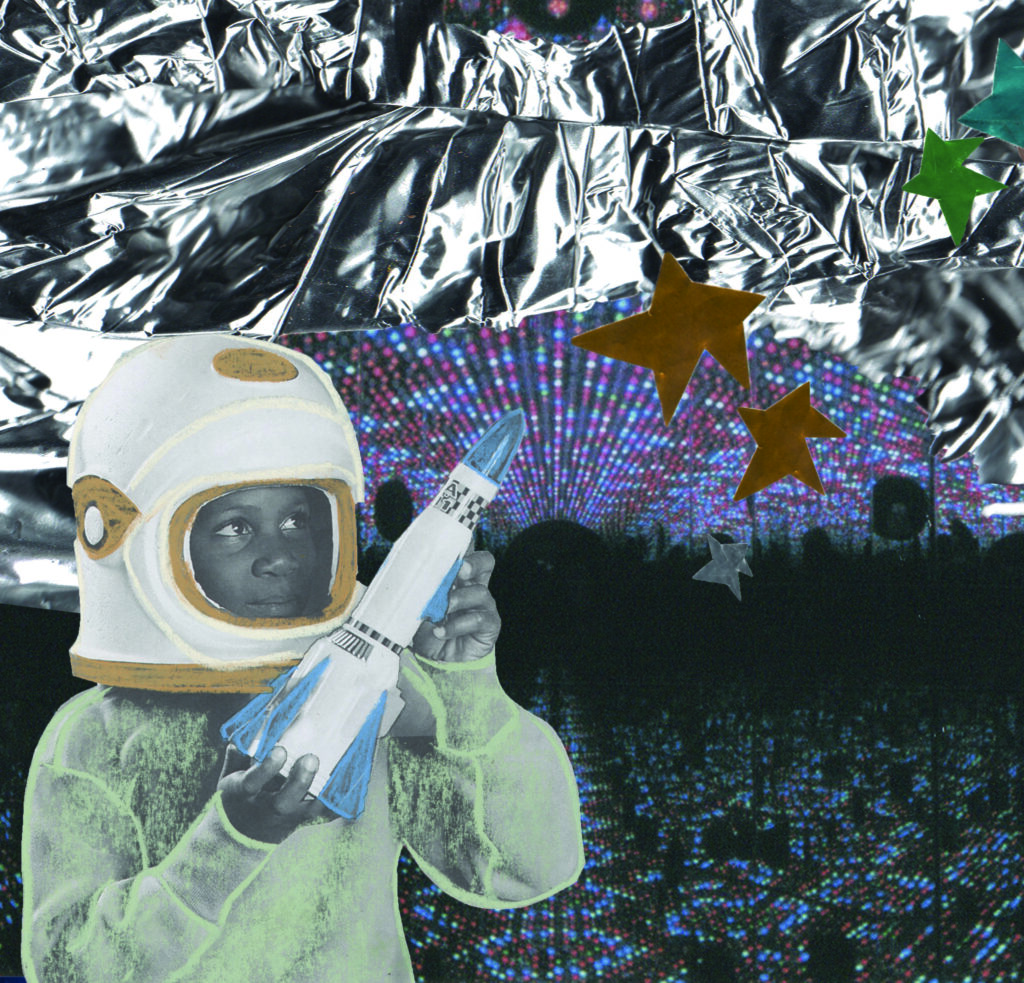

Bell-McKoy: I keep thinking, is that rocket science? Doesn’t this benefit all of us? But it feels like rocket science some days in having the conversation because you’re really asking people to rethink, to relearn how they were taught in terms of that history that wasn’t given to citizens. A lot of the positive history hasn’t been available about Black and brown people. I find myself on a reading journey right now learning as much as I can more about the history of black and brown people in this country.

And it’s important…for us to do the hard work now because we’re now awake much more across the country. That’s why I’m passionate about it. It’s been my journey all of my life. It was my journey at UMBC. It’s been my journey around what can I do, how can I make a difference for Black and white people?

UMBC Magazine: You’ve been doing this work for so long. What do you tell young people who are looking to make change?

Bell-McKoy: There are many ways that you can help in the now, including doing your own reading, your own research about why this exists. There are lots of opportunities locally—particularly now that we’re in a virtual world—to join lots of webinars and conversations across the country so that you can more deeply educate yourself. And because we have the ability to touch people all across the globe through the virtual environment, there are opportunities for students to be a mentor, for them to add some value to someone’s life.

Continue to use creativity, continue to use all your genius to make a difference in people’s lives. But understand that also—as you get to the next stage in your career coming out of UMBC and you’re becoming a millionaire—you need to invest back in all those organizations trying to change the system knowing that you can become a part of the patient capital needed to achieve system changes that then benefit a greater number of persons. You do have to steel yourself for the incremental. This may mean when the big change comes, many of us may not be here to benefit from it, but…that’s a part of it. It has to be an intentional journey.

RIPPLE EFFECT

For Jason Grant ’10, M17, a defining moment happened on a bus ride to a Meyerhoff Scholars event at UMBC President Freeman Hrabowski’s house his freshman year.

A senior asked Grant about his major (computer engineering) and then proceeded to pepper him with specific questions about his classes and his plans for graduate studies. That brotherly interest, says Grant, turned out to be the norm, not the exception.

“People kept telling me,” remembers Grant, now an assistant professor of computer science at Middlebury College, “if you go to UMBC and join the Meyerhoff program, you’re going to have a community of people. I didn’t actually realize how important that was, but it turned out to be extremely critical.”

In their careers, Grant and many other Meyerhoff alumni are replicating that family atmosphere—valuing the unique contributions of each member and raising up others alongside them around the country.

Immanuel Williams ’11, M18, mathematics, grew up doing math worksheet after math worksheet, his father handing him new problems to solve and instilling a desire to understand complicated equations. So later in life, when his colleagues made assumptions about how as a Black man, his father must have been missing from his life—he stopped them short.

He and his wife Kelley Williams ’13, environmental studies, wrote a book called The Adventure of Jamear: Shapes All Around, which celebrates the relationship of a father helping his son discover math. For Williams, a lecturer at California Polytechnic State University, the book launched his work at six Boys & Girls clubs around Los Angeles and San Francisco, providing math boot camps for hundreds of elementary school students for the past three summers.

Williams taps his own college students as volunteers to help personalize all the feedback students receive. “We’re reaching marginalized communities in terms of race and economic status,” says Williams, “so that feels really good.”

Grant has carried the Meyerhoff vision to Vermont, where he’s taken on leadership roles for the small population of students of color at Middlebury to see a face that looks like them. As advisor for the Black Student Union, “it allows me to network and to get a feel for the climate of all students of color here in this predominantly white institution, and how they’re trying to navigate that space,” says Grant, current president of the Meyerhoff Alumni Advisory Board.

This year at the ACM Richard Tapia Celebration of Diversity in Computing Conference, Grant served as deputy chair for research competition and poster competition. “This made me put my money where my mouth is,” says Grant. “Telling students to go to the conference was one thing, but them seeing me on the conference program allowed me to be a vocal leader in that space as a professor.”

Nicole Parker ’11, M19, biochemistry and molecular biology, now works as a lobbyist, connecting research institutions with federal dollars. She sees her role to advance policies that broaden minority participation in STEM and increase diversity in science and engineering careers. She puts it plainly: “I’m passionate about making changes so that the entire biomedical research enterprise operates like the Meyerhoff program.”

The ripple effect of the Meyerhoff program is clear—whether in K–5 after-school programing, at rural universities where representation is crucial, or lobbying Congress to fund research programs for scientists from diverse backgrounds.

“In four years at UMBC, those Meyerhoff values are so ingrained in us every day,” says Parker. “You can’t forget it when you go on to the next place.”

— Randianne Leyshon ’09

SUPPORT SYSTEM

As protests sprung up in cities across the country this spring, alumni like public historian Allison Seyler ’10, M.A. ’12, history, and computer programmer Carlos Lalimarmo ’11, computer science, found themselves compelled to participate. Today, as the nation continues to contemplate ways of making change, they, like so many others, are thinking deeply about how to be good allies to people of color.

UMBC Magazine: What ultimately drives you to participate?

Seyler: As someone who deeply loves Baltimore City, I try to stay informed about the issues our community faces; one of those issues is police brutality. The longer I have lived here, the more I learned the necessity of making time to listen to Black leaders—women and men—who wholeheartedly devote themselves to this city; they have been calling for police reform for years. So for me, the choices I’ve made to protest this year were linked to that. I felt in order for me to show up for the Black community in Minneapolis who are mourning George Floyd, the Black community in Louisville who are mourning Breonna Taylor, and really, to show up for Black folk across the nation, I needed to show up for Baltimore.

Photo courtesy of Lalimarmo.

Photo courtesy of Seyler.

I had these eerie flashbacks to marching for Freddie Gray and felt an all too familiar sadness that families have lost their sons, daughters, fathers, sisters so unnecessarily. As I felt a sensation of “this is happening again,” my heart just dropped. How could we be at the same point we were in 2015? I think I’m driven to participate as a human being who cares intensely for others, but also because I believe that collectively, protestors can use their voices and actions in sustainable ways to force real change to happen.

UMBC Magazine: What do you see as your role as an ally and how do you hope it will be seen by others?

Lalimarmo: I think being informed is the baseline for participation, whether you agree with demonstrators’ message or not. You can’t participate responsibly without being informed. The protests themselves have become an issue, and the best way to understand them is to experience them firsthand. So I go when I can. When I think I understand and agree with the message of a particular protest, I’ll stand or march with the group to show support.

UMBC Magazine: What would you say to someone who isn’t sure of how to get involved but would like to?

Lalimarmo: I think a lot of people who would like to be more involved but aren’t sure how are probably more involved than they realize. Supporting the people close to them is important work that I’m sure they’re already doing. If not, strengthening personal relationships is a solid place to start.

Seyler: Honestly, I would remind them that there’s no better time. And I would channel two mantras that are said often, but get to the core of this work: This is a marathon, not a sprint. This is a movement, not a moment. If someone wants to get involved and is looking for a starting point, I would suggest starting with something small and human: read memoirs by Black authors like D. Watkins, Kondwani Fidel, and Chris Wilson. Pick up a copy of A Beautiful Ghetto by photographer Devin Allen and fill your mind with images that show the beauty of other peoples’ humanity. Sign up for a workshop by activist Britney Oliver to learn about being anti-racist in your actions and words. Your actions and involvement makes a difference.

ADVOCATES FOR CHANGE

Recently, there have been calls across the United States to defund the police and correctional facilities in response to the continued violence from police toward the Black community. But what exactly does defunding the police mean for youth currently in the juvenile justice system and for those most at risk of entering?

For 30 years, UMBC’s Choice Program has engaged, mentored, trained, and advocated for more than 25,000 youth in Maryland. It provides a series of programs to disentangle young people from the juvenile justice system and to strengthen youth and family ties to the community through increased educational and vocational opportunities.

UMBC’s Eric Ford, director of The Choice Program, and Frank Anderson, a doctoral student in language, literacy, and culture and the associate director of programs, talk about how the Choice model can provide a complex answer to a complex problem.

Anderson: What is defunding the police and what does that mean for Choice?

Ford: Defunding the police means reallocating funds to diversion programs so that youth will not get involved in the criminal justice system. It means investing in providing training to first responders in communities across America around restorative practices or providing additional mental health and substance abuse support for young people. Reallocating funds to these programs means communities will be able to provide the interventions and supports needed to individuals who are now being criminalized.

What do you think, Frank? What is our moral responsibility in this work?

Anderson: It’s important for me to reflect about what my moral and ethical responsibility is and whether my moral checkbook balances out at the end of each day. Am I creating more opportunities than what I’m taking? Am I working to share and distribute more resources than what I am taking? If not, then maybe it’s time for me to move to the side. I’m grateful you and peers are there to hold me accountable to keep pushing myself everyday to understand my role within the greater community.

What personal value of yours makes this work so important?

Ford: Truth. Being able to build on our Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation (TRHT) framework has been such a rewarding experience for me. It has validated a lot of my personal beliefs, personal goals, and what I learned at Hampton University. For so long discussing the truth about what has happened in the past to marginalized people has been taboo in certain spaces. Being able to share the truth about my ancestors and people who have come before me and have it embraced has been transformational for me. This is exactly what our TRHT work aims to do. We support communities and a process to foster important difficult conversations around race equity and transformation. I am thankful for it every day.

Anderson: You are the longest-standing person of color to lead Choice. What about that makes the job difficult? What about that excites you?

Ford: My first position at Choice was as a caseworker. That experience led me to other opportunities. I returned to Choice to be assistant director and worked my way through the ranks. Ascending to the director of Choice is something I am very proud of. As a man of color, you always carry the weight of your racial or ethnic group and the weight and pressure to be successful. Coming into this position, I experienced some imposter syndrome sitting in spaces that I had not been before and wondering whether I belonged in those spaces. Over time I have gained confidence through feedback I have received from my peers, my mentors, and my family.

It has been a wonderful experience to not only represent Black men and represent all the participants of color and young men of color. I represent a possibility for them. One of my proudest moments at Choice was when an AmeriCorps member was introduced to me in my office. He was a young Black man. He looked around my office and was in awe. He said, ‘Wow, this could be me one day.’ It hit me that it’s not just about reports, proposals, and grant writing but it is also what I represent for Black men throughout the country.

INCLUSION MATTERS

Created in June, the UMBC Inclusion Council brings together faculty, staff, students, and alumni from all across campus to help address issues of equity and inclusion at UMBC. UMBC Magazine talked with the council co-chairs, Keith J. Bowman, dean of the College of Engineering and Information Technology, and Ariana Arnold, director of the Office of Equity and Inclusion about what’s ahead for this group.

UMBC Magazine: What have the first meetings of this group been like? How would you describe the energy in the (virtual) room?

Bowman: We began with several weeks wherein everyone could talk about their experiences, visible and non-visible elements of their backgrounds, and their commitment to the work. It was an incredible set of meetings where folks expressed their passion for the work of the Inclusion Council. It made me feel truly proud of our UMBC community and its commitment to social justice.

Arnold: It was extremely meaningful…because we never met until we were already virtual. So we felt like it was really important to make those personal connections. I think that really started us on a good path for people being able to be honest when having discussions about sometimes difficult topics, as well as being compassionate towards each other, which is really what we’re trying to build here.

UMBC Magazine: The Council no doubt has a lot to think about and plan (everything from curriculum, faculty and staff diversity, to intersectionality and restorative practices, etc.). What issue or project are you personally most excited to work on, and why?

Arnold: I would love to be on all of the committees…but I’m really excited about the work of the faculty and student retention and belonging groups. We had 146 people interested in being part of those working groups, which was amazing. And these are both places where we can have a significant impact on the campus.

Bowman: I am most excited about being able to provide a platform and mechanisms to elevate the work that many have been doing more towards substantive actions.

UMBC Magazine: What do you hope people will be saying about this work a year from now? Or five years down the road?

Arnold: What I’d like to be able to say a year from now is that we are doing the work and not just, you know, talking about the work. And that five years from now we’ve had a measurable impact on campus in terms of both inclusivity…meaning that people from all political, racial, ethnic, religious, cultural backgrounds, abilities, and nationalities have become engaged and that we’ve improved the sense of inclusion and belonging on campus.

Bowman: I hope they can see visible and defined changes, but I also hope they continue to have expectations since we know success is never final at UMBC.

CALL TO ACTION

In 2017, Christine Osazuwa ’11, interdisciplinary studies, left the country. She eventually settled in London—a place where she says she’s never seen quite so much natural integration of people of all races, cultures, and walks of life. Even so, when the news of the death of George Floyd reached her this spring, Osazuwa, director of data and insights for Warner Music Group, never felt quite comfortable expressing her feelings in the form of public protest.

“There’s nothing like a pandemic to remind you that you’re an immigrant…. I’m a guest in someone else’s country,” she says, noting she can’t vote, either.

So, instead, she did what she does best—she wrote about it. What started as a short series of Facebook posts fueled by her own life and experiences eventually became a longform essay titled “How To Be a Better Ally.” In five steps—consume content and goods made by Black people, question your employers and your privilege, for instance—Osazuwa implores her white friends, ultimately, to take the time to familiarize themselves with the Black experience.

Osazuwa grew up within a first-generation Nigerian American family in a predominantly white suburb of Baltimore.

“I know all about Hanukkah, I can pronounce the last names of my Polish friends, I know basically every word to Mean Girls, I can dance to “Cotton Eyed Joe,” I can sing along to “Sweet Home Alabama,” I can name all of the Kardashians, and I’ve had my fair share of meatloaf and coleslaw…. Obviously, these are mostly trivial, stereotypical examples but the point is, I have grown up surrounded by white culture,” she writes. In creating this piece, she hopes to give readers a push to learn about Black culture without adding to the weight [Black people are] already carrying.

“As a white person, you can get through life completely fine without ever understanding another person’s culture,” she explains. “There was no expectation the other way around. I had to know your shows and mine. I had to read your books and mine. I had to know your history and my own. And now, we say it is not our job to educate you because we’ve spent our entire lives learning and doing everything twice.”

Read Osazuwa’s full piece on LinkedIn.

*****

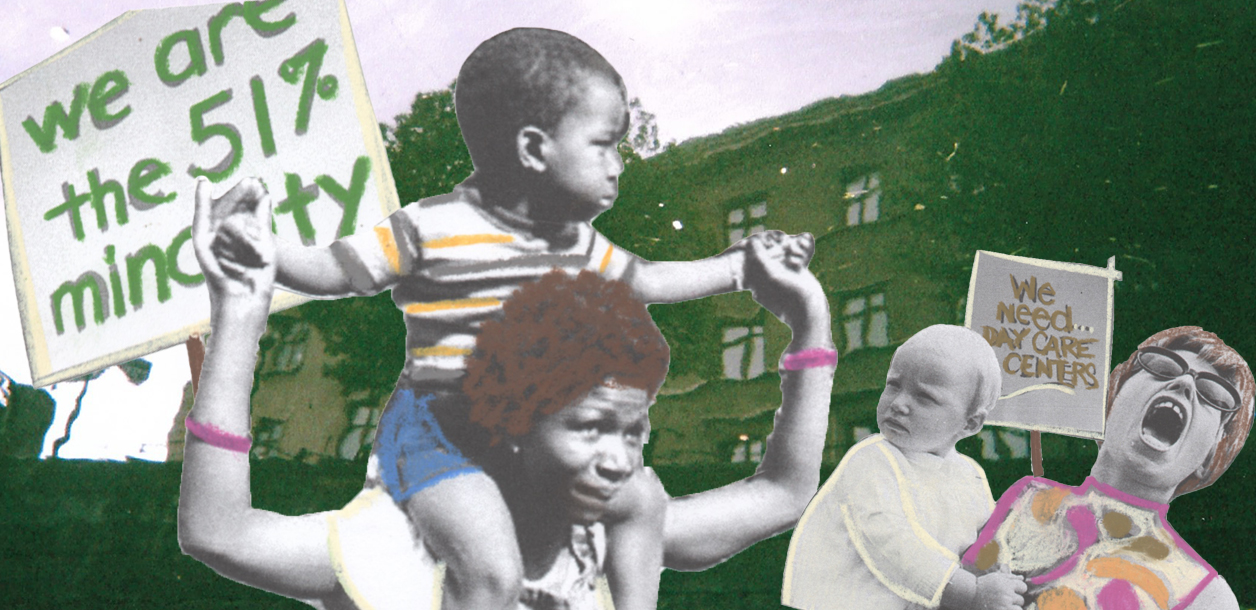

Stories and interviews by UMBC staff. Illustrations, including story header, by Elise Peterson.

Tags: Fall 2020, UMBCTogether