with Andrew Haberman ’21, computer science, and Davina Orieukwu, assistant Track & Field coach

It’s widely accepted that you need to practice a skill for 10,000 hours before becoming an expert. Andrew Haberman ’21, computer science, has a different number in mind—20,000 throws. Twenty-five throws a practice, five days of practice a week, 10 months out of the year for four years. And even after that, he knows that success is never final. So he makes another throw.

Along with shot put, weight, and discus throws, Haberman specializes in the hammer throw. This is not a tool from your dad’s shed. For men’s regulation competition, it’s a 16lb metal ball attached by a steel wire to a grip. While the object of this competition is—like all throwing competitions—to launch your object the farthest, with hammer throw speed is also a big factor.

Andrew Haberman

Davina Orieukwu

As part of track and field, throwing is more obscure than some events, but UMBC has a storied history in this discipline. Cleopatra Borel ’02, interdisciplinary studies, is a four-time Olympian shot putter representing Trinidad and Tobago, placing 7th in Brazil in 2016.

On the practice field, again and again, the rhythmic sound of Haberman’s shoes scuffing the throwing circle are followed by a thunk as the hammer lands in the grass, a rooster tail of dirt following each toss. Haberman and his throwing coach, Davina Orieukwu, talk through foot placement, chest height, release angle, and many other minute readjustments to his technique. Over and over, Orieukwu reminds him, “push the hammer all the way around,” to get the most efficient throw. So how does anyone get to 20,000 throws? Start with the first one.

Tools of the Trade

- A hammer—This implement is a 8.8lb (for women) or 16lb (for men) metal ball on a wire with a handhold. But in a pinch, other heavy implements attached to a chain and grip will work.

- Wide open space—this is not a sport to practice near a lot of windows.

- Upper body strength—this would be helpful to start, but you can always build it up while you practice.

- A coach or mentor—no YouTube video can substitute for hands-on guidance.

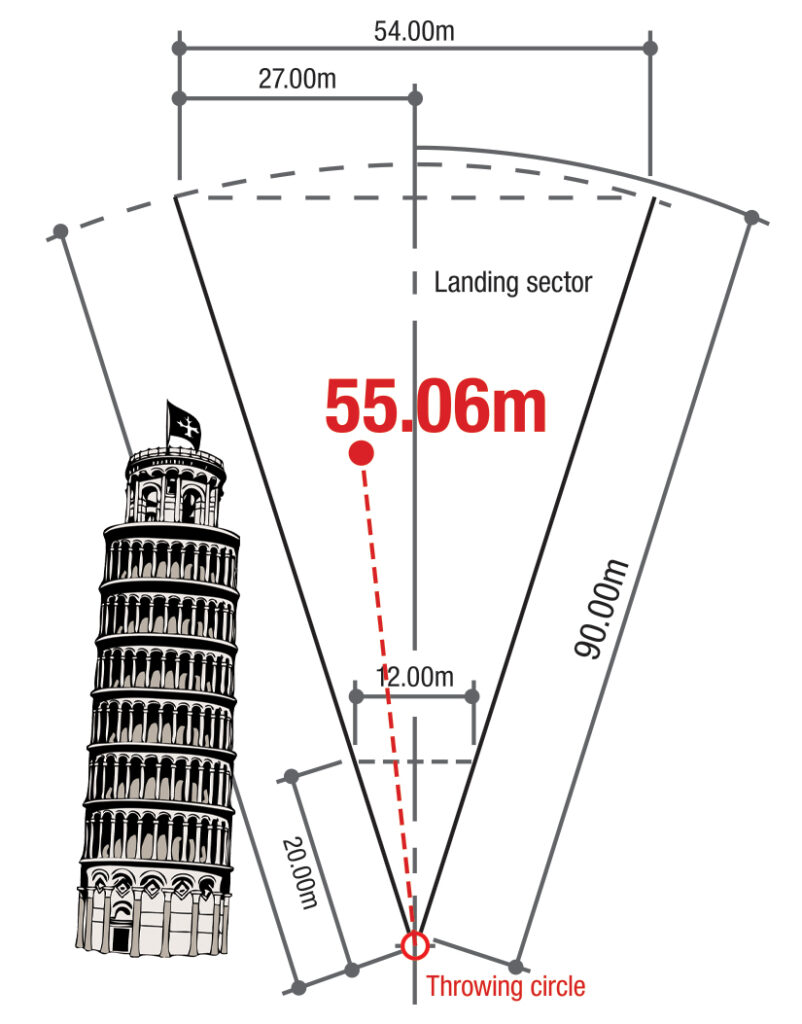

Haberman’s career record toss is 55.06m (180.6 ft). That is approximately as long as the Leaning Tower of Pisa is tall. Illustration by Jim Lord ’99.

Step 1 — Hammer time

First acquire a hammer or throwing implement. These aren’t the most accessible pieces of equipment like a pair of running shoes or a soccer ball. Hammer throw isn’t a part of most high school track and field teams, but Haberman’s coach at Century in Carroll County had access to some of the heavy equipment and allowed the throwing athlete to practice on his own. Haberman saw the hammer throw as a way to extend his athletic career, gaining experience in a more uncommon discipline to make him a more attractive athlete to colleges.

But you don’t need a regulation hammer to start off. During practice, Orieukwu has Haberman and another throwing athlete, sophomore Thomas Hamby, use a variety of weighted objects. First, Haberman warms up with a literal ball and chain. This implement weighs twice as much as the hammer he’ll use in competition, so he’s gaining strength and developing better technique by handing the heavier object. Hamby throws a hefty chain looped around a handle to start.

Step 2 — When, not if, you fall, get back up again

Hone your technique. Maybe at first this is watching YoutTube tutorials by world class athletes or binging compilations of “fails,” to see all the ways that things could go wrong. As Orieukwu repeats during practice, “losing connection with the ground is losing connection with the ball.” For the uninitiated, stumbling or falling down is to be expected in the beginning. Imagine this: you are trying to balance your body while swinging a weighted ball over your head twice and then spinning anywhere from three to five times (called “the wind”), building up momentum to the moment of release. The faster the speed of your spins, the more velocity your hammer has.

Everyone, says Haberman—even with four years of experience—loses control of the ball. The key, he notes: “Be as relaxed as possible, but strong and intentional at the same time.”

Step 3 — Arm & hammer

Learn better form. Haberman says his STEM background certainly helps, as he thinks through the physics of the pull of the hammer as his body rotates to gain speed. Orieukwu tells him to watch his “flat 2.” Haberman knows that means during his second rotation, “my hammer rises really high in my orbit, so that keeps me from throwing farther,” he says.

As the ball increases velocity with each turn, it’s important to retain a triangular shape with your arms—your chest forming the base, your arms the two legs of the isosceles triangle, and the hammer at the vertex. If the hammer gets ahead or behind your triangle, you’re in trouble, says Haberman.

Step 4 — Pass it forward

Start mentoring others. So much of hammer throwing is a mind game, shares Haberman, who credits older team members with helping him learn good habits early on: relax, make jokes during practice, and stay neutral to avoid emotional highs and lows which can derail an athlete. Hamby, who just picked up the hammer throw in fall 2020, says that Haberman, now a senior, is his go-to source for advice.

The older athlete sees his responsibility and tries not to pass long throwing neuroses. “I consistently think I can do better, but sometimes that works against me,” says Haberman. “Thomas picks up on my attitude and I don’t want it to negatively affect him.”

With that, he lifts the hammer, executes the wind, and completes another throw—number 20,001 and counting.

*****

Header image: Haberman practices with Orieukwu looking on. All photos by Marlayna Demond ’11.