Anyone who has had the pleasure of a rooftop visit with Freeman A. Hrabowski knows the joy UMBC’s president takes in pointing out the Baltimore skyline from the top of the Administration Building. That’s because Baltimore — to him, and to UMBC — is not just a nearby spot on a map or a place to watch a baseball game. It’s a life source for the university, providing internships for our students, jobs for our graduates, and culture for all who may choose to take advantage of it.

As much as UMBC receives from the city, however, it also gives back in immeasurable ways, in service and partnership. Every day, members of the UMBC community — faculty, students, staff, and alumni — collaborate with neighbors across the city through art, civic and social service, environmental activism, storytelling, and education projects. The stories that follow highlight just a few of the many, many ways UMBC is making an impact in its beloved Baltimore.

Full STEAM Ahead

It has been a year since UMBC and Northrop Grumman launched a partnership in three Baltimore City schools, sparked by a $1.6 million commitment from the Northrop Grumman Foundation. The partnership, which includes Baltimore City Public Schools and the Department of Recreation and Parks, boosts science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) education both in and out of school. The work is centered at Lakeland Elementary/Middle School in Southwest Baltimore and is changing how these students, and their families, see science in their futures.

A primary focus of the program will be the development of a state-of-the-art STEAM Center at Lakeland that will feature science labs, a makerspace, digital video and sound studio, computer lab, parent resource room, and community meeting space. The recreation center attached to the school is in the process of getting a complete makeover, but even during construction planning, the new STEAM programs are already happening. After school, girls are learning to design and build apps in the Technovation club, and students are working on robots for Vex Robotics.

Students showed off the work in the first ever STEAM family night, bringing almost 70 students and community members to the school to learn about science together. With more than just financial support, volunteers from Northrop Grumman are now a constant presence in the school, serving as coaches, mentors, and even celebrity readers.

Four years ago, UMBC President Freeman Hrabowski and Lakeland Principal Najib Jammal met to lay the groundwork for collaboration inspired by the vision and philanthropy of George and Betsy Sherman. The partnership that emerged brought UMBC’s Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars Program, Shriver Center Peaceworker Program, and The Choice Program to Lakeland.

“The impact of this partnership goes beyond institutional philanthropy. It provides meaningful learning opportunities for all partners, from Lakeland and UMBC students, to teachers and professors, to STEAM professionals,” explains Rehana Shafi, director of the Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars Program at UMBC.

Beyond STEAM, the partnership also helps Lakeland and other schools build stronger communities. Northrop has supported the expansion of The Choice Program, a highly successful national model for community-based intervention that has served more than 20,000 youth and their families from Maryland’s highest risk communities for almost 30 years. Through the partnership, The Choice Program has expanded to serve students and their families, including former Lakeland students, at Benjamin Franklin High School at Masonville Cove and Excel Academy at Francis M. Wood. At Lakeland, STEAM center staff plan activities for parents, including a food pantry, community Zumba, and free tax preparation. Once the new computer lab is complete, the center will also start offering job training classes.

“We are going to work with our colleagues to prepare these children to compete against anybody, anywhere in the world,” said President Hrabowski. “We want to be saying that we can take children from any background…and make them best in the world. It takes that village, and it takes…hard work.”

— Max Cole and Marie Lilly

Hands-On Science

What exactly is in our water? Through a partnership between UMBC and area schools, students can explore worlds beyond what’s visible by the naked eye.

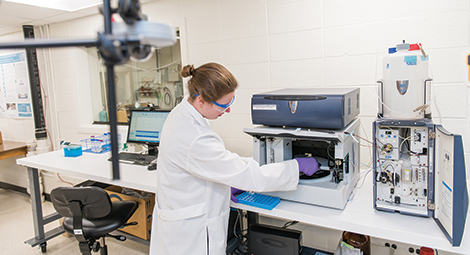

“Science is premised on asking questions about our world and seeking answers through the scientific method. Students learn best through doing,” says Dean Bill LaCourse of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences. Unfortunately, many schools have limited resources to practice science using advanced instrumentation, he explains, but UMBC’s RAIL, or Remote Access Instrumentation Laboratory, can help close that gap.

Through the generous support of Battelle, UMBC is using RAIL to leverage technology to bring high-end analytical instrumentation to elementary, middle, and high school students across Maryland. Housed in UMBC’s Molecular Characterization and Analysis Complex, RAIL aims to increase teacher content knowledge while inspiring the next generation of scientists and researchers in STEM.

Teachers receive training at UMBC to use remote-access software to connect computers in their classrooms to the instrumentation in the RAIL studio. They also learn procedures for collecting water samples RAIL can test – from the Patapsco River to a playground puddle – which they send to UMBC for analysis on RAIL. When the teacher and class make contact with RAIL, a UMBC scientist is available to answer questions via the lab’s two-way video capability. Then the class can remotely operate the instrument as it analyzes their samples and view the data it produces in real time – from pollutant content to salinity. Over the last year, the system has been implemented in schools in Baltimore City and Harford County, and the goal is to greatly increase the reach of the program.

“RAIL will be the basis of a new model for outreach by UMBC,” LaCourse shares, “to provide opportunity and inspiration to students from every corner of the state, including Baltimore City.”

— Sarah Hansen M.S. ’15

Making the JUMP to College

Nepal is a world away from Baltimore in miles of land and ocean. But for those who find they must leave their home there, making that trip is only the beginning of their journey.

“I cannot speak what’s on my mind. I stop because of my language barrier,” said Sushmita Thapa, a Western High senior who had to leave Nepal with her family in 2015 because of the political unrest. Despite the difficulties, she says, “I want to be a doctor. I want to be an independent woman, and I want to help others.”

Thankfully, she has an ally in that process – Hannah Sadollah, UMBC sophomore and mentor in College JUMP (Journey Upward Mentoring Program). Since September, Sadollah has met with Thapa weekly, giving her tips on how to take the next steps to getting into college – from crafting essays to navigating financial aid.

“It hurts my soul that she has the potential to get into college but she wouldn’t have been able to get in because she doesn’t know how to apply,” said Sadollah, who is studying to become a psychiatrist.

Sadollah and other college students acting as mentors in College JUMP aim to enable high school juniors and seniors who are refugees (or asylees, seeking asylum) with crucial college application and life skills. The program came about two years ago through a partnership between UMBC and the Baltimore City Community College Refugee Youth Project.

Christie Smith ’15, global studies, coordinates the program through AmeriCorps. She says partnerships like Thapa and Sadollah’s work well because “they build off each other’s energy” and are both so motivated. It also helps that, like most of the mentors, Sadollah’s family has an immigrant background. She came here from Iran when she was a baby.

“This gives me an awesome opportunity to give back,” said Sadollah, who learned these skills in high school. She said Thapa is “soaking it up,” to the point where four of her college applications have been accepted, including one to UMBC. Now, like all college-bound seniors in the U.S., she has to figure out what will work for her in her ongoing education.

“I’m learning every day,” said Thapa, “I’m trying to fit into this society every day.”

— Karen Stysley

Charm City Connections

It’s a little chaotic during closing bell at Excel Academy, located on Baltimore’s west side. Teenage students, giddy with the excitement of an unseasonably warm March day, flow in and out of the library — drawn equally to the PlayStation that has been set up and two young men just a few years older than the high school students themselves.

UMBC students Ramses Long ’17, biology, and Jabari McLain ’19, financial economics, are visiting the library to tutor, mentor, and connect. They are members of Charm City Connection, an organization of UMBC students, most of whom also went to school in the city and who want to build relationships as role models and mentors with Baltimore City students.

These after-school sessions are only one of the club’s endeavors, but it’s unique in simplicity and impact. Long, McClain, and the other members are not trying to change policy or act as saviors. They have partnered with UMBC’s Shriver Center to help students with homework, studying, writing a paper – or maybe just getting them into class – on a weekly basis. Excel Academy is an alternative high school for students at least two years behind grade level – usually over-aged, under-credited, and facing a plethora of problems in their homes and neighborhoods.

“We’ve gotten students to commit to their goals. One student didn’t come to school on a regular basis and never came on Fridays. We got him to start coming to school on Fridays,” says Long about the basic nature of their approach. “Another student needed help writing a paper and was behind. We worked on the paper during the after-school session, and she got it in on time.”

Understanding the small steps to achievement like attending class, completing homework, and a few hours of studying, make the Charm City Connection mission humble and effective. Showing how accomplishments like passing a class and moving to the next grade level put goals like graduation, college enrollment, and job placement within reach.

The PlayStation might be a trick to get students into the library after the closing bell rings, but it works. Charm City Connection members have built an honest relationship with Excel Academy students, beyond just tutoring.

“We engage students in conversation to help them contextualize their experiences, so they aren’t as confused by the obstacles they are facing,” says Long. “We want to empower these students to do something for themselves and communities.”

— Alice Crogan

Proof of Life

UMBC student Amy Berbert ’17, visual arts, is in the midst of an ambitious yet somber project: using photography to memorialize each of the 318 victims of homicide in Baltimore in 2016.

Berbert began taking photographs at crime scenes in the city last year with the goal of bringing visibility to the traumatic impacts of violence on people and communities. Her year-long senior thesis project, which she posts on the Instagram feed @stainsonthesidewalk, is described as, “An Exploration of Homicide in Baltimore City. Same Day. Same Time. Same Place. One Year Later.” Each death is memorialized with a picture taken precisely one year later at the location of the homicide.

The photographs “are respectful of the people involved,” she told Mary Carole McCauley in the Baltimore Sun. “They don’t judge anyone. It’s just a moment of silence to remember these people, and the fact that they lived and died in that place.”

Though Berbert’s senior exhibit concluded her college career, she is dedicated to continuing the rigorous project through the end of the year, planning her life in 2017 around the lives that were lost in Baltimore in 2016.

By focusing on increasing awareness of lives lost through violence, Berbert hopes to encourage others to engage with and support communities facing challenges. She shares, “As a community we need to educate ourselves and others about the root causes of violence…step out of the bubble of campus and immerse ourselves in understanding the issues that people right down the road from us face every day.”

The broader impacts of Berbert’s work aren’t yet fully realized, but she’s already felt the project’s effects on herself. As she told the Baltimore Sun, “Before I started working on this project, I knew I had stereotypes. But, every time I go out I’m faced with them. I don’t know if this project is going to change anyone else. But, I think it’s changing me.”

Berbert notes the similarity in age of herself and many of the victims as well as perpetrators. “It has inspired me to learn how differences in circumstances and environment can lead two equally human people down two very different life paths. We all want to feel safe, provided for, accepted, and sometimes noticed. As I have read about the victims and the perpetrators of these homicides as well as spend time in the neighborhoods and talk with people who experience the struggles of these neighborhoods, I have learned that we really are not so different.”

— Catherine Borg

Walking the Walk

When the students disembark the UMBC Shuttle at MLK Boulevard, their tour guide Kate Drabinski, lecturer in gender and women’s studies, turns the group to face the subject of the day: a part of downtown Baltimore they have likely not explored before this day.

They start walking, stopping to discuss the B&O Railroad Museum, the Bromo Seltzer Arts tower, and other landmarks. With each of these points of interest, however, there is a division as tangible as the short brick wall dividing one side of MLK from the other. The rise and fall of industrialization, the spread of the arts community, and the building of new neighborhoods comes at the expense of demolishing others.

The group goes quiet at the University of Maryland Biopark, a physical reflection of what comes down when something new is built. Boarded-up houses still surround vacant lots reserved for development.

“When we cut those people off from our imagination, then it makes it easier to destroy them,” says Drabinski, who offers the walking tour in conjunction with the Women’s Center Critical Social Justice Week. “From talking to students, their parents say ‘Don’t go to Baltimore. Baltimore is so dangerous.’ But that kind of rhetoric is dishonest … and it justifies the civic abandonment of these places and that is not ok.’”

At the end of the tour, Drabinski leaves the students with a final lesson. They must find lunch and figure out their own way back to campus so they can learn not only about the layers of history within the different places, but also the logistical barriers of getting there and back.

“Stuff that is a little bit scary,… part of the struggle is having someone give you permission to go into that space,” says Drabinski. “As a tour guide or as a teacher I can say, ‘I invite you;’ that is the first step. Just like in class, if I call on you on the first day and you hear your voice, you are more likely to talk through the rest of the semester. With the walking tour, if someone takes you somewhere and shows you how to do it … someone shows you the first steps they are more likely to do it again.”

— Kristen Russell

Making Good CHOICEs

At the dinner table, J’Monnie Walker and his four high school clients act like a family. Their plates piled high with the abundance only a college all-you-can-eat buffet can provide, they joke over ice cream, mac and cheese, pizza, and smiley face french fries, with day glo green soda to wash it all down. They ham it up for a group photo like siblings.

Then Walker, a fellow with the Choice Intensive Advocacy program, which is run by UMBC’s Shriver Center, gets serious.

“Tell me what this program is about,” he says, directing the question to 15-year-old Ja’Bria, a city high school junior who wears a cat ear headband and a welcoming smile.

“When I started the program, I was not a happy person,” explains Ja’Bria, who has missed more than her fair share of school days over the last semester for reasons we don’t discuss tonight. “But now … I’m a happier person. I try to be warmer.”

“Do you feel better?” he asks her. She nods. And her attendance record reflects it.

Students who are referred by a state agency into the six-month program find themselves paired with a fellow, like Walker, who visits the school at least twice a week, and the home once a day. Walker is like an extended member of the family, he says, even teaching the students how to cook. Tonight, they’re at Loyola University for a “College Night,” which he hopes will help them see opportunities beyond the challenges of their lives.

“I just want people to see them the way that I do,” and not judge them by their transcripts, he says. “The best part is the progression you see, the window that opens.”

— Jenny O’Grady

Calm in a Storm

Intimate partner violence (IPV) can happen anywhere, and it largely goes unreported and untended. For veterans in the Baltimore area, however, a pilot program created and staffed by UMBC alumni and faculty is setting new standards for care and prevention of this particular type of violence. The Baltimore Veterans Administration Medical Center is among the first of 17 national pilot sites for Strength at Home, a 12-week group-based program developed by Casey Taft Ph.D. ’01, clinical psychology.

“Our programs focus on preventing violence from occurring in the first place, or else ending that violence once it begins,” says Taft, who originated the program at his home base of Boston, and whose recently published trials prove the program to be a bona fide success.

Over the course of three months, small groups of veterans who have been referred to the program meet for two hours at a time to discuss in depth the best ways of responding to stressful situations, the difference between assertive communication and aggressive or passive communication, and other related topics.

“We have been amazed at the receptiveness that we have received at the Baltimore VA, and how invested folks there have been in working to end violence in military and veteran families,” says Taft. “We expect to see the program continue to grow and to be considered the place to refer veterans and service members who are experiencing difficulties with anger and aggression in their relationships.”

IPV Assistance Program Coordinator Julia Caplan ’07, modern languages and linguistics, notes an added benefit is having Taft’s mentor Chris Murphy, professor and chair of the psychology department, just a short drive away. An expert in abuse and violence in intimate adult relationships, Murphy also serves as a trainer for the program.

“We are lucky that we have Chris down the road because they’re training people all over the entire United States. So Casey is in Boston, his co-coordinator is in Texas, and Chris is here,” she said, and Taft agrees.

“His presence there ensures that there will always be incredible local expertise in partner violence intervention and a steady stream of highly competent providers and trainees who will carry on this effort.”

— Jenny O’Grady

Tags: Amy Berbert, Baltimore, Choice Program, College JUMP, Lakeland Elementary, RAIL, Spring 2017