UMBC assistant professor of sociology Zeynep Tufekci investigates how we use Facebook, Twitter and other new social-networking services to define ourselves.

UMBC assistant professor of sociology Zeynep Tufekci is not a big fan of technology for its own sake. But if a new electronic gadget helps her get through the day more easily, she is all for it.

Take the baby rocker, for instance. She loves this device. On a summer day at home on maternity leave, Tufekci replaces the hulking C batteries of a pendulous crib that gently rocks her seven-week-old boy to sleep. Babies enjoy an easy back-and-forth motion when sleeping – the rhythmic lull reminds the infant of comfort of the womb. This crib creates a few minutes of space for Tufekci to attend to other matters.

The best technology not only solves human problems, but it can actually change our world – sometimes in ways we don’t fully recognize. And Tufekci has become one of the country’s most called-upon academic experts in explaining how new technologies of social networking—such as Facebook and Twitter—are changing the way we live. She has been interviewed by the New York Times, the Philadelphia Inquirer and other media outlets about the topic.

Although the term “social networking” is relatively new, the concept has been around since at least the 1980s, when people found that bulletin-board systems (which were nothing more than personal computers that other computers could dial into) provided a virtual meeting ground for exchanging messages, jokes, photos, recipes and anything else of interest.

From those humble beginnings, such virtual spaces are becoming an increasingly large part of our lives. Facebook alone reports having over 200 million users. And these spaces have impacts on external events. In June, thousands of disgruntled Iranians logged onto Twitter, another popular service that allows users to post 140-character messages for others to see, to protest the outcome of their presidential election. The cumulative effect of the angry and informative bursts of information from Tehran and elsewhere in the country not only brought more global news coverage to the election, but also helped protestors evade disruptions of mobile telephones and other messaging services by the government .

“People wonder why these technologies spread so much,” Tufekci says. “It’s kind of like asking: ‘Why do people like foods that are high in salt and sugar?’ Being deeply social is part of being human. It is part of your biology.”

Limits to the Digital Self

Researchers theorize that the average person can, at most, maintain cognitive relationships with about 150 people. Not surprisingly, then, the average number of the people who are “friended” in a typical Facebook user account is about 120, according to the company that runs the service.

Tufekci studies how social networking blurs the boundaries between public and private spaces, a topic she came across almost by accident, thanks to a group of students who “took a short cut they shouldn’t have,” she says.

In an introduction to a sociology class she taught, five students turned in sheets to a quiz with identical handwriting. When she confronted the students about it, they all swore that they didn’t know each other. She already knew they were acquaintances, however, even if they didn’t sit together in class. Each of their Facebook profiles had listed the others as friends. Eventually, they ’fessed up.

After Tufekci disciplined the students involved in the incident, she reflected at greater length on the interaction. “What got me really interested was the fact that these were very smart students, but they did not figure out that their Facebook profile was public,” she says. “I saw that these students are conceptualizing Facebook as a private place, but it is potentially a very public space.”

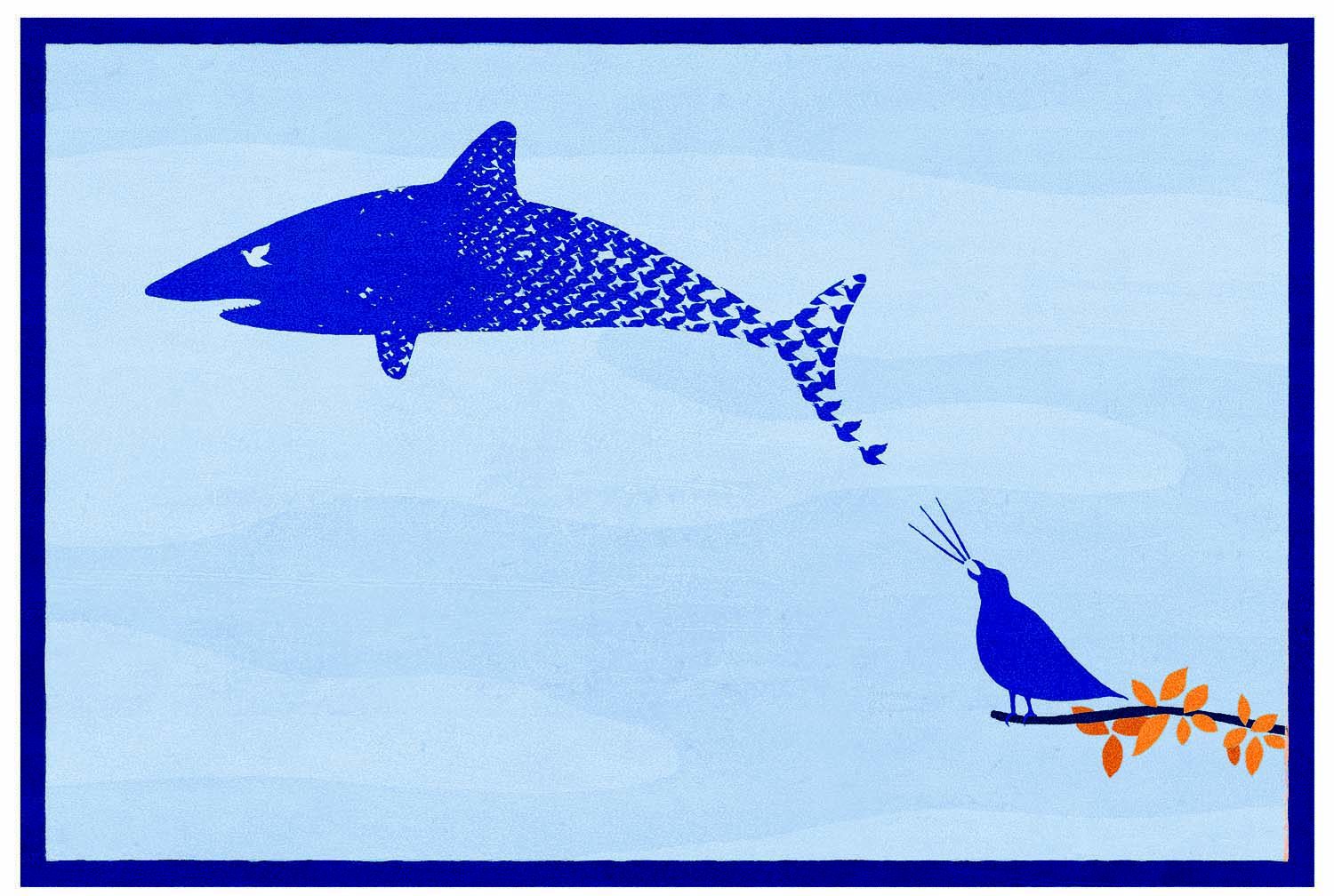

Tufekci found this peculiar conflation of private and public in digital space revealing. She argues that social networks are a natural extension of our social lives – albeit with some subtle but important differences. When the use of the Internet first became widespread in the mid-1990s, many assumed that users would adopt new roles online, expanding beyond the confines of their physical selves. “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog,” was the caption of a famous New Yorker cartoon of the time.

But this perception that one has the ability to create a new self online largely hasn’t turned out to be the case. Most people use the Internet in general, and social networks in particular, as an extension of their lives, rather than as an alternative to them. “They want to do mundane things. They want to do people things,” she says.

Sam Gosling, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Texas at Austin who also studies social media, agrees with Tufekci. Social media, he observes, “is kind of like the telephone. It’s a new technology for expressing the sorts of things we need to do anyway.”

A Slippery Space

Nonetheless, such online social gathering spots can differ from our normal meeting places, such as a friend’s house or a restaurant, in subtle ways that most users don’t fully appreciate. This disparity in perceptions is what Tufekci’s work centers upon.

In a study published last year in the Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, Tufekci examined the actions and perceptions of 704 college students who used Facebook. A peculiar conundrum emerged: Many students expressed privacy concerns about posting information in a public forum. Yet their concerns did not inhibit them from posting a great deal of revealing information about themselves – including their relationship status, their birth date and their cellular telephone numbers.

What are the dangers of having such information out there? In the real world, two individuals may meet and have a conversation. Both people see each other and the conversation fades into their memories. We traditionally think of this interaction as a private conversation. With social-networking sites, however, those same words can be preserved for the ages, and they are available for others to see.

“Usually intimate interactions are in closed space, and public spaces are civic stuff and they are not intimate. Here we have intimate stuff that is public,” Tufekci says. This “collapsing of the boundaries and conflating of characteristics of private and public spaces” can muddy the way people think about how to use such spaces, such as underestimating how many people will actually see that photo of late-night merriment that you posted only for a few friends.

“I’m a big fan of her work,” says Timothy Finin, a professor in UMBC’s Computer Science and Electrical Engineering Department who studies ways to bridge machine languages and human languages. “We’ve developed an understanding about information-sharing based on the physical world. And a lot of those same intuitions don’t apply to the virtual world, and that’s where people can run into problems.”

Talking about Tufekci’s work, Finin is reminded of something called the Wason Selection Task, in which sociologist Peter Wason showed that people may use a different part of their brains for thinking about social rules than they do for solving abstract problems. “Maybe, while on the Internet, you do most of the thinking with your [logical] part of the brain you use with the computers, and not the social part,” Finin says.

Computer Science to Social Science

Tufekci is no stranger to large, sprawling communities. She grew up in Istanbul, which, with about 12 million residents, is the fourth largest city in the world by most estimates. She actually started her career not in sociology, but in computer programming. But she found herself more fascinated by the social effects of technology than with the minutiae of the C programming language.

After taking a Ph.D. at the University of Texas at Austin in 2004, Tufekci studied the effects of technology on low-income people. As part of her research, she followed a group of people going through a computer-skills training program that held out the promise of high-paying jobs upon the completion of the courses.

“That was a time when people were saying that the Internet would solve everything for everyone,” Tufekci says. “I found it was not so great for people, especially if you are low-income and available jobs are being automated and outsourced.”

Tufekci’s work spans multiple disciplines – sociology, social psychology, computer science, psychology, anthropology and communications. “My work doesn’t fit into an existing discipline. It’s fairly grounded in sociology, but it has been very interdisciplinary,” she says.

Gosling observes that Tufekci’s work is “dispersed over many disciplines, many of which have difficulty talking with each other.”

UMBC has been instrumental in helping Tufekci follow this emerging field of study. When she was in the academic job market, she wanted to find a university that was open to her pursuit of a multi-disciplinary approach.

Surprisingly, such schools were hard to locate. While many hiring committees voiced appreciation for the benefits of studying across departmental lines, they were shyer about hiring such a wandering academic.

At UMBC, however, Tufekci says that she found kindred spirits.

“They hired me knowing that I would be cutting across different disciplines,” she says.

It would be a mistake to dismiss social-networking services as a fad. MySpace and Facebook are this year’s popular virtual destinations for many, and their influence may fade within a few years, but chances are they will replaced by other services. Social-networking services have gained their present popularity by reflecting both innate human behaviors and contemporary trends.

By and large, the Internet started out as a male-dominated domain. But in another 2008 study, published in Information, Communication & Society, Tufekci found that the gap has closed. More women than men whom she studied used Facebook, by a slim margin. “What this showed was that if you have the kind of application that is appealing to women, then they are perfectly willing to adopt it,” she says.

In the same study, Tufekci also found that the difference of how men and women used social-networking services reflected traditional gender roles. Men would use services as a search mechanism for finding things on the Internet. (“What they were searching for, we never found out,” Tufekci jokes.)

Women, by contrast, use such services to connect with existing friends. “I thought this is so stereotypical. You think we’re past that – but apparently not,” she says.

At present, Tufekci is working up an academic review that she hopes will explain how social networks fit in the larger picture of how people have traditionally related to one another. For Tufekci, the use of social-networking services represents a return, in at least some aspects, to a time when we lived in smaller and more close-knit communities.

Only in the past 150 years or so have the vast majority of people left their villages to live and work in larger cities, she notes. Such moves to larger urban centers have brought about a sense of isolation and even alienation, to judge from popular analysis from books such as 1950’s Lonely in the Crowd (written by David Riesman, Nathan Glazer and Reuel Denney) and 1956’s The Organization Man (William Whyte). In many ways, the social-networking sites are returning elements of this older way of living to us, for better and for worse.

“That is the kind of environment our species has lived in for the past 100,000 years,” Tufekci says. “We’re not going back to the village, but we’re bringing back some of its aspects. I want to explain why this is an important development in human history. The questions on the table are not trivial.”

Find UMBC Alumni On Facebook.

Tags: Fall 2009