UMBC is so firmly established in the Baltimore region and as the home of over 80,000 Retrievers, it’s hard to believe that only four decades ago, our university was in danger of being permanently shut down.

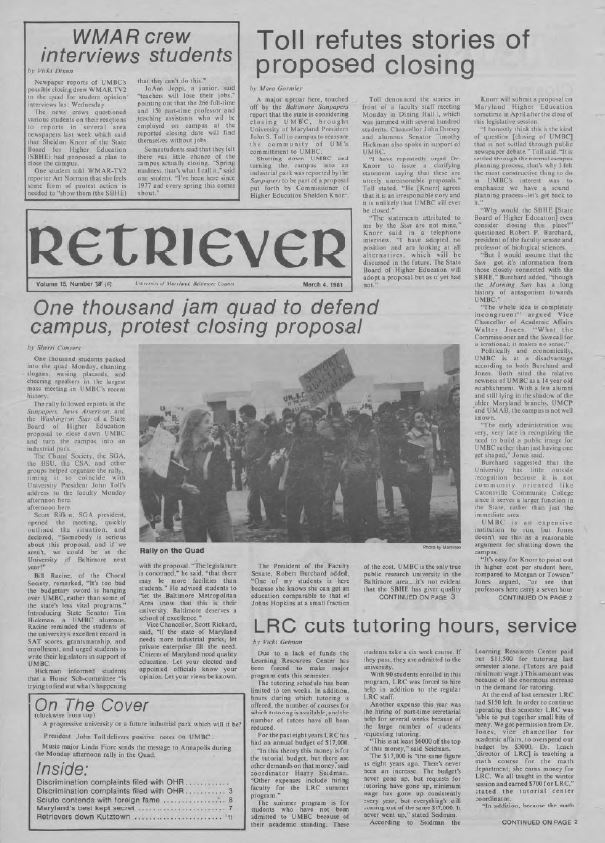

Picture this: On March 2, 1981, a thousand UMBC students and faculty gathered in the Quad chanting into megaphones, shouting cheers, and proudly waving poster exclaiming, “SAVE OUR SCHOOL!” Local TV news crews flocked around the protest gathering footage of UMBC’s largest mass meeting to date. “Up your nose, we won’t close!” students cheered as they marched to the dining hall to await a speech from then-Chancellor John Dorsey and UMBC President John Toll to discover the fate of their beloved university. Was UMBC going to be shut down indefinitely?

One of the largest rallies in UMBC’s history was sparked by controversial reports released by the Baltimore Sun Papers, News American, and the Washington Star stating that the State Board of Higher Education (SBHE) may submit a proposal to turn the Catonsville campus into an industrial park. The proposal was put forth by the commissioner of higher education, Sheldon Knorr.

Toll denied that there was any legitimate threat, but students were unsatisfied with such a simple response and clamored for more answers.

A rally to remember

As reported in the March 4 edition of The Retriever, multiple student groups such as the Student Government Association, Black Student Union, the Chinese Student Association, and others helped organize the rally. SGA President, Scott Rifkin ’81, biological science, shouted his frustrations and roused the crowd of students.

“Somebody is serious about this proposal, and if we aren’t, we could be at the University of Baltimore by next year,” he said followed by deafening roars of approval, according to the student paper.

Students stood on tables, chairs, and each other’s shoulders to get a glimpse of Toll as he delivered his speech to the agitated crowd.

“The newspaper reports were demoralizing and damaging,” Toll said. “If the threat is real, we are prepared to fight it.”

Current UMBC archivist Lindsey Loeper ’04, American studies, created an online archive summarizing the raucous event for the university’s 50th anniversary. While gathering the information for the archive, she noted a certain joy in immersing herself in this historical event.

“There are so many myths and stories about UMBC’s history, and one that I remember hearing was about Chancellor Dorsey standing on the table in the dining hall and addressing the crowd of students—I wish I had a picture of it,” she says. “It was interesting to see the event unfold through the newspaper clippings and administrative records and correspondence. The SBHE proposal really seemed to blindside a lot of people.”

Reason for concern

While the administration denied reports of the university closing at the time, there were many reasons why UMBC may have been on the chopping block. The relatively young 14-year-old university had few alumni and still laid in the shadows of the older Maryland institutional branches. University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland at Baltimore had a combined 300 years on UMBC, leaving the school politically and economically disadvantaged. UMBC also lacked a public image, something that then-Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs Walter Jones asserted, was the early administration’s fault.

“The administration was very, very late recognizing the need to build a public image for UMBC rather than just have one shaped,” Jones said in The Retriever article.

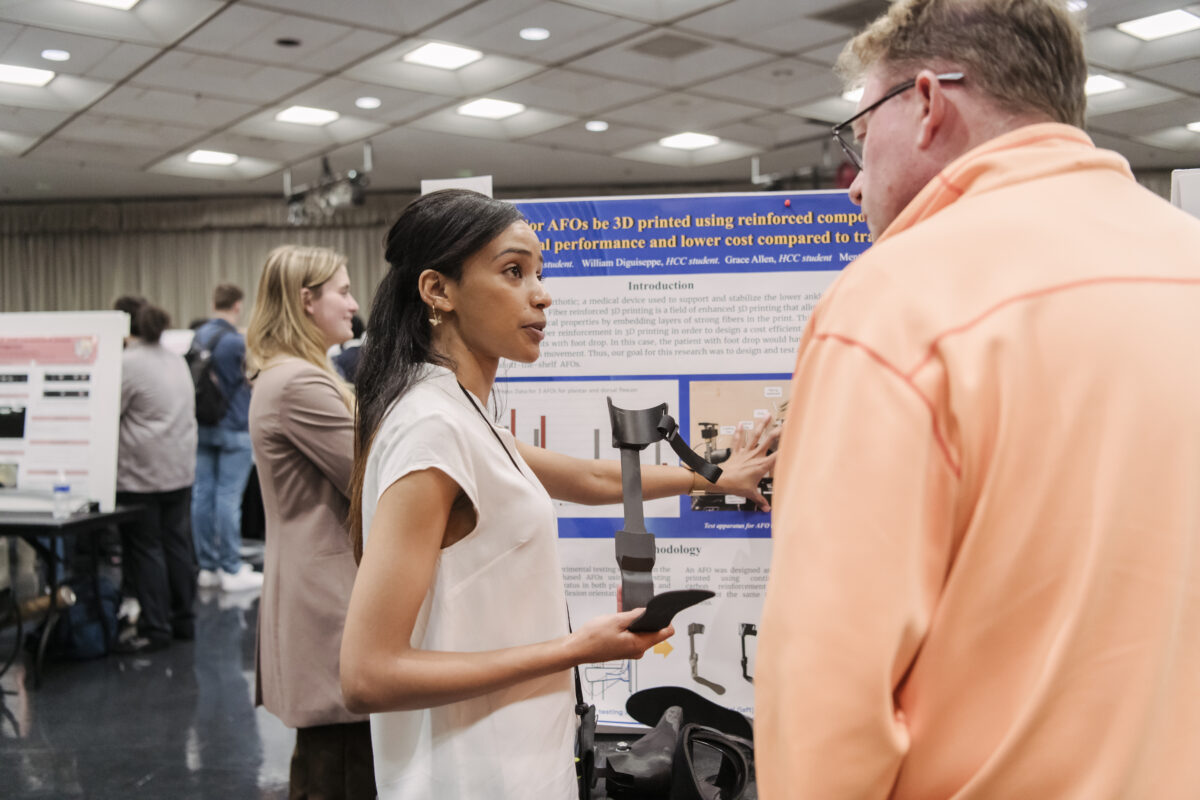

The fundamental problem was that the SBHE failed to understand the purpose of a “research-based” university, noted Jones, who asserted that UMBC required a closer student-teacher ratio and that a specialized laboratory open year-round was necessary to the growth of the university. He stressed the importance of a higher education public research institution in the Baltimore area.

The research-based vision continues to guide the development of UMBC, and also defines the current reputation of the institution. UMBC is regularly recognized for its teaching and innovation as well as faculty research.

“This event was one of a number in the 1980s that shows how UMBC was trying to figure out where it fit in the academic community in Baltimore, in Maryland, and in the larger national scope,” Loeper asserts. “I think it shows that universities continually go through periods of stability and periods of change.”

Where would we be without UMBC?

The SBHE would eventually adopt a proposal in April 1981 that left UMBC untouched and allowed the campus to remain open. Nearly 40 years later, UMBC and its alumni have changed the trajectory of countless lives through the years—students have gone on to serve as the U.S. Surgeon General and be voted in as the first African American and first female Speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates; they also work behind the scenes to create the sounds and ambiance that so many of us enjoy in the Star War franchise. Yet none of this would’ve been possible had campus been turned into a bleak industrial park.