Once upon a time, Joseph T. Jones, Jr. thought he couldn’t escape the city’s mean streets. Now he’s leading efforts to help reclaim the families broken by urban ills.

By Elizabeth Heubeck ’91

Photos by Bruce Weller

Searing waves of heat already ripple through West Baltimore at 9 a.m. on a Friday in July. The streets around 2201 N. Monroe Street – headquarters of the Baltimore-based nonprofit Center for Urban Families (CFUF) – are all but deserted.

Inside the center’s air-conditioned conference room, 40 or so adults – men and women, black and white, some as young as 18 and others old enough to be grandparents – sit in neat lines of metal folding chairs, sweating a

bout their future. Some look anxious, others bleary-eyed. Most of the men wear ties, pressed pants and dress shoes; the women are in heels, panty hose and skirts. Some are ex-convicts. Many have been involved with the drug trade. Others have held jobs but haven’t been able to keep them.

If the room has the solemn air of a funeral, there’s a good reason. Everyone here is preparing to say goodbye to their old lives and start anew through the CFUF’s signature program, STRIVE, which is modeled after a prototype launched in New York City’s East Harlem.

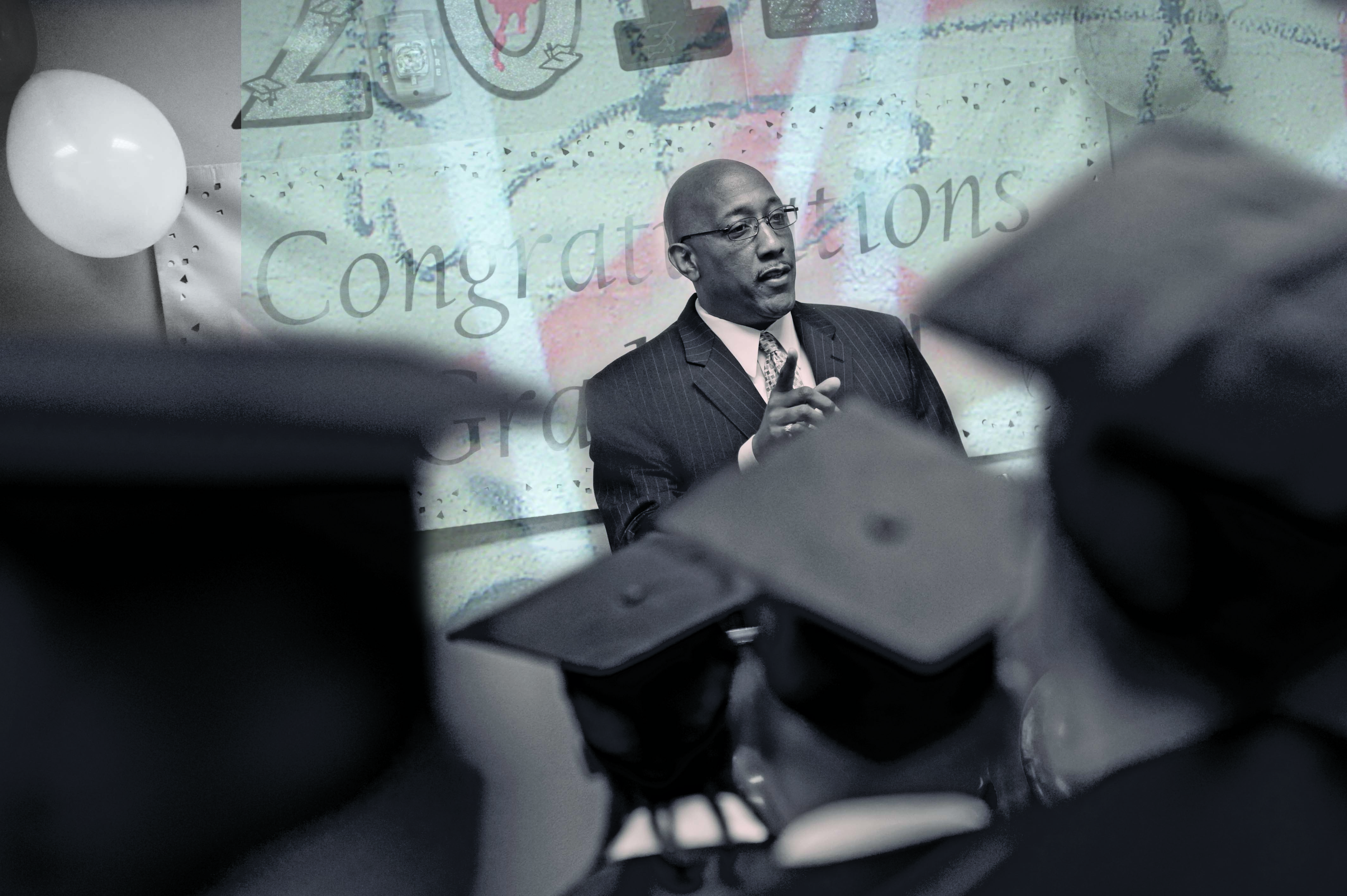

When the center’s founder and CEO, Joseph T. Jones, Jr. ’06, social work, walks to the front of the room, everyone seems to sit up a little straighter. Standing more than six feet tall in a dark blue pin stripe suit, Jones’ imposing stature and deep, authoritative voice command the room. But his story also grabs attention with this audience: He’s walked a remarkably similar path.

“All the things I did suggest I should be dead, incarcerated, or debilitated,” Jones tells the group.

Jones’ path was particularly rocky: He was the product of a broken family. He shot heroin at 13, and was arrested for the first time at 14. He spent more time in Maryland’s juvenile justice system than he did in a high school classroom. And Jones’ career as a drug dealer saw him only narrowly escape a lengthy federal prison sentence.

But Jones is living proof that hard knocks don’t always knock you out. His West Baltimore center promotes stable career paths and rebuilds strong family units among urban residents, and Jones is sharing his successes with national audiences – including meetings with former Vice President Albert Gore, Jr. and a place on President Barack Obama’s Taskforce on Responsible Fatherhood and Healthy Families.

Healthy families are the building block for any American renaissance, argues Jones. “Twenty-five million children live in households where their fathers are not present. As a society, we can’t have that number of children not having a relationship with their fathers.”

Rough Beginnings

Rough Beginnings

Jones remembers the breakup of his own family at age nine with chilling clarity.

“My father, he was ex-military,” Jones recalls. “I remember him packing his [military] duffel bag one day.” Jones watched from the living room window, which overlooked the entrance to East Baltimore’s Lafayette Courts projects, as his father put his duffel bag in the car and drove away. Life with a single mother left Jones “crossing boundaries,” as he puts it. He became friends with a crowd that plunged him into heroin use and selling drugs. And his first drug-related arrest and sentence to 30 days in a juvenile detention facility didn’t exactly scare him straight. “One of my best friends from the street was there. He created a seamless pathway

for me to have no trouble in that system,” Jones recalls. As Jones cycled in and out of the juvenile justice system and grew ever-deeper roots to drugs and crime, a part of him remained open to a different path. Ironically, it was Jones’ father, barely present in his life since leaving with his duffel bag, who planted the seed on a visit to his son in juvenile detention.

Jones’ father brought him Manchild in the Promised Land, a book by Claude Brown which tells the story of the author’s coming of age (and escaping) poverty-stricken and drug-filled 1960s Harlem. The book led Jones to other influential autobiographies, including those of Martin Luther King, Jr. and John F. Kennedy.

“I was preparing myself for now, but not intentionally,” Jones says. “I was always attracted to stories about people who were making change in society.”

Almost Lost

Jones says he had a talent for masking problems under a façade of normality. He managed to earn his GED, attend community college, and was even admitted to a management training program with the Social Security Administration.

Under that surface, however, Jones remained unchanged. Indeed, he was brazen enough to sell drugs out of the Social Security Administration building.

He believed he was successfully evading police detection until one day he was asked to attend a meeting during work hours in the organization’s auditorium. When he arrived, he was greeted by members of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency.

Jones recalls the arrest was “a complete embarrassment.” His mother and grandmother also worked at Social Security Administration, and dealing in that building brought a federal drug charge. He was also suspended without pay and removed from the management training program.

Eventually Jones pled guilty to a misdemeanor and avoided jail time. But even that humiliating arrest did not create a final break with his addiction to heroin and cocaine and his drug crimes. For years, he observes, “faith and fate” allowed him to narrowly avoid lengthy jail sentences.

Jones started to weary of the game, however. On October 3, 1986, he knocked on the door of Spring Grove’s residential drug treatment program. “Part of me wanted to stop doing drugs,” Jones recalls. But the real motivation was to avoid a jail sentence for five new criminal charges. The choice was simple: drug treatment or jail.

A year in drug rehabilitation helped Jones finally make a break with his former life. For the first time since he could remember, he was sleeping and eating well and exercising regularly. At year’s end, Jones was ready to commit to the “phase out” stage of the treatment program, which required him to have a plan to continue his recovery. Jones decided on the community college degree he’d started but never finished.

Now in his thirties, his experience at Baltimore City Community College (BCCC) was decidedly different after rehab. Jones became the top student in the college’s accounting program. He also met his future wife, Debra Scovens, who was an assistant to BCCC’s dean of admissions.

They have now been married for 21 years and have three children. Armed with a new family and newfound confidence and stability, Jones was ready to pursue helping others change their lives as he had changed his own.

Making Waves in Public Policy

Jones took several part-time jobs to make ends meet during community college. One job involved working with a community-based organization that provided health and HIV/AIDS education, where his primary role was negotiating contracts with drug treatment centers and providing health and HIV education to their clients.

Jones parlayed that job into a grant-funded position with the Baltimore City Health Department to ensure that pregnant women in the city received prenatal care. As he worked with these women, he had an epiphany about the connections between their challenges and his own upbringing. “I’m dragging these women from crack houses to prenatal care,” he recalls, “then they’re going home to these guys who were saying, ‘We need help, too…. Public policy wasn’t addressing the issue of fatherhood.”

Health officials urged Jones to take up the cause on his own. And he did. Using the federal government’s Healthy Start Initiative, Jones developed and implemented a “Men’s Services” program within the city health department’s Healthy Start program.

His success with that initiative provided Jones with invitations to high-level conferences on urban families, including one hosted by Vice President Gore and his former wife, Tipper Gore. At that conference, Jones chose to make a splash when he was asked to comment.

“I went off on a tirade about the surface level of the conversation, and how it didn’t meet the needs of the people in the communities where I come from,” Jones recalls. And though he received a round of applause for his outburst, he felt compelled to apologize to Gore for his strong words. That day allowed Jones not only to establish a personal relationship with Gore, but it also garnered him more invitations to discuss the obstacles facing urban families.

Back to School

Jones’ persuasiveness about the importance of jobs and reconnecting families to create an urban renaissance also found an audience closer to home. UMBC president Freeman A. Hrabowski, III, attended one of Jones’ speeches and was impressed.

“It was clear he was a masterful communicator,” says Hrabowski. “He was analytical, used his own story and was able to talk about intervention strategies. Most importantly, he spoke with great authenticity.”

When Hrabowski queried Jones about his education and learned that he had an associate’s degree, he didn’t withhold his opinion. “My first reaction was that he had to go back,” Hrabowski recalls. “I knew it would open more doors for him.”

Jones demurred at first, telling UMBC’s president that he was too old, that he had a young family, and that he didn’t qualify for scholarships. But Hrabowski eventually won out, serving as Jones’ mentor as he took his degree at UMBC. In 2006, at the age of 50, Jones graduated cum laude from the university.

“His standard of excellence is so incredibly high,” Jones says of Hrabowski. “He uplifts you just being in his space.”

Success and Standards

Jones’ dynamic presence provides a similar uplift for the men and women he’s working hard to help at the Center for Urban Families.

Take STRIVE. On its surface, the program is a boot camp for coping with the challenges of the contemporary workplace: being on time, dressing appropriately and managing office hierarchies. But it’s also a “reboot” camp to help clients gain self-assurance and self-reliance in all areas of their lives.

“When you see people who come in here, and you look in their eyes,” Jones observes, “there’s almost no hope. You have to convince them that if they follow the structure we have established, they can be successful, regardless of their background,” he says.

At the first day of the STRIVE training on this July morning, most participants come dressed in their best clothing. But one young man, dressed in baggy black pants and untucked shirt, didn’t get the message. Jones summons him to the front of the room.

“Did they explain to you what you had to do to prepare for today, including the dress code?” Jones barks. “Do you want to go through this program?”

The young man’s response is barely audible.

“You’ve got ten minutes to get dressed like this guy,” says Jones, pointing to a man in the front row wearing a dress shirt and slacks, wing tips, and tie. The young man saunters to the back of the room and out the door.

Jones tells those who remain: “We’re going to raise the standard real high, and some of people are going to fall off…. Twenty percent of you won’t be back on Monday.”

When Jones worked for the Baltimore City Health Department, he designed and oversaw innovative programs like STRIVE. But the bureaucracy of working within a government agency frustrated him. “If I wanted to grow beyond now, I knew I couldn’t do it at the health department,” he says. With a nod from his then-boss and former Baltimore City Health Commissioner Peter Beilenson – and financial support from the Abell Foundation and its longtime president, Robert C. Embry, Jr. – Jones was able to strike out on his own.

In 1999, Jones opened the doors to the Center for Urban Families. In the attractive new building in which the nonprofit is housed today, Jones has also started a program to help fathers: Men’s Services Responsible Fatherhood program. The center also launched its first national initiative, Baltimore Building Strong Families, in 2005. The program aims to support new low-income parents with financial know-how and relationship skill building.

Tough Love

Jones attributes the success of the center’s initiatives to a tough-love approach that provides structure and demands discipline. It’s this approach that attracted longtime supporter David L. Warnock, CEO of a Baltimore-based investment firm. He’s been the chairman of the 12-year old nonprofit for more than eight years.

“I like the tough love approach to STRIVE,” says Warnock. “I also like how the model of STRIVE aims to create a sense of accomplishment among a group of people that doesn’t feel much in the way of accomplishment.”

The number of lives touched by STRIVE is also impressive. As of August 2011, more than 4,000 men and women in Baltimore have graduated from the program. And the center has been able to place more than 3,900 of its graduates in jobs with an average starting wage of $8.80 an hour.

Jones relishes telling personal success stories about STRIVE graduates, including La’Roy Charles Alston, Jr., a former gang member in Baltimore City. Two of Alston’s friends were shot within a week. Then Alston himself was shot twelve times and lost a leg. Though he thought about retaliating, Alston decided instead to give STRIVE a try.

“He was saying that he wanted to do something different. Now, he’s getting ready to graduate from Sojourner-Douglass College. He has one of the most infectious personalities, despite living with chronic pain,” says Jones.

Checking back in with Jones on a sunny Friday in August, he’s busily preparing new federal grants for the center and addressing a new class of STRIVE graduates, who enter to strains of “Pomp and Circumstance” decked out in blue caps and gowns.

Jones acknowledges that these graduates are facing some of the toughest economic times in recent memory, but he underscores that their commitment holds the key to success in surmounting it: “Remember when I told you on the first day that we were looking for a few good men and a few good women? You are the few good men and few good women.”

Jones also urges the new graduates not to get complacent. He wants to see them all back at the center bright and early on Monday morning, starting the job hunt.

“We’re going to have your back,” Jones says. “As long as you stay connected.”

Tags: Arts, Baltimore, East Harlem, Fall 2011, Folding chair, Jones, Joseph T. Jones Jr., Shopping, West Baltimore