|

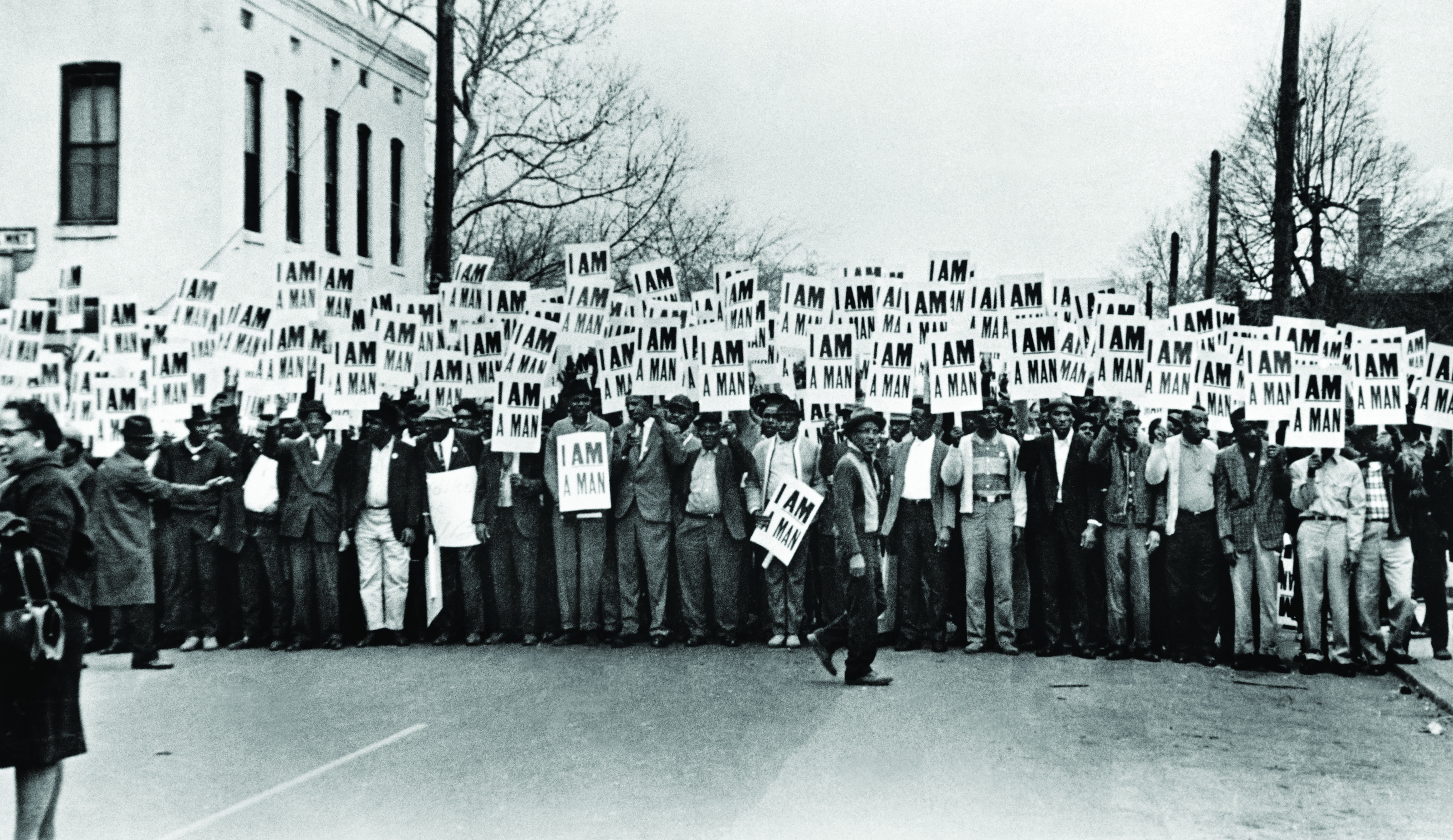

Ernest C. Withers

Sanitation Workers Assembling for a Solidarity March, Memphis, March 28, 1968

Gelatin silver print National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution

This image from the African American photographer Ernest Withers—one of the most famous pictures of the civil rights era— stands as a tribute to the slain leader Martin Luther King, Jr. and a poignant reminder of the continued urgency of the struggle he died for. The photograph also reminds us of how important visual culture was to the epic battle against racism and segregation, depicting as it does not just protestors but the placards carried by black sanitation workers in the strike that brought the civil rights leader to Memphis, Tennessee on the day of his murder in April 1968 – an event immortalized in this now iconic photograph. |

|

Negro Baseball Pictorial Yearbook, 1945

Collection of Civil Rights Archive/ CADVC-UMBC, Baltimore, MD

For more than 75 years, black players were banned from major league baseball. In response to this unwritten policy, the Negro leagues were formed in the late nineteenth century, a collection of professional baseball associations made up of predominantly African-American teams. The Negro leagues issued posters and handbills for distribution to black audiences, typified by this Negro Leagues yearbook from 1945. Its players were routinely covered in African-American periodicals, but remained invisible in the mainstream media. |

|

Sepia,November, 1959

Collection of Civil Rights Archive/ CADVC-UMBC, Baltimore, MD

The birth of the black pictorial magazine was an important event in civil rights history. Publications such as Ebony, Jet, and Tan (the first black women’s magazine), Our World, Say, and Sepia – the magazine illustrated here – played a major role in promoting affirmative black imagery in a popular culture awash with negative depictions. These publications emphasized photo-essays about African-American achievement and celebrity but also reported on the harsh reality of racism. The magazines’ upbeat content catered to subscribers and sponsors alike, providing readers with pictures that defied stereotypes and advertisers with stories that sold the idea of black success, stability, and affluence. |

|

Screen Capture from The Ed Sullivan Show, c. 1966

(Ed Sullivan, The Supremes: Diana Ross, Florence Ballard, Mary Wilson) Courtesy The Ed Sullivan Show/SOFA Entertainment

While simultaneously entertaining Americans of all races, The Ed Sullivan Show (which ran from 1948 to 1971) did much to advance the cause of civil rights. If prime-time dramas and situation comedies of the civil rights era rarely featured African-American actors or subject matter, the program actively showcased black acts, making it a civil rights trailblazer. By depicting black and white performers interacting as equals, and by bringing these entertainers into the homes of millions of Americans, black and white, on a weekly basis, the program set an example of racial acceptance and integration, not just for the entertainment industry but for the nation at large. |

|

Lunchbox and Thermos: Julia, 1969

Collection Civil Rights Archive, CADVC

Julia (NBC, 1968-1971) was one of the earliest weekly, nationally broadcast built around a contemporary black character. The series centered on the everyday life of Julia Baker, a recently widowed nurse—played by Diahann Carroll—and her young son. Many critics viewed the show as groundbreaking, because of its refusal to promote racial stereotypes: Julia was intelligent, self-sufficient, well dressed, and beautiful, a far cry from the black servants and buffoons of 1950s television. If Julia broke ground, though, it did so in ways that would not intimidate white viewers: the main character rarely interacted with black friends or associates; she readily excused white people’s bad behavior; and she never demonstrated racial awareness or pride. |

|

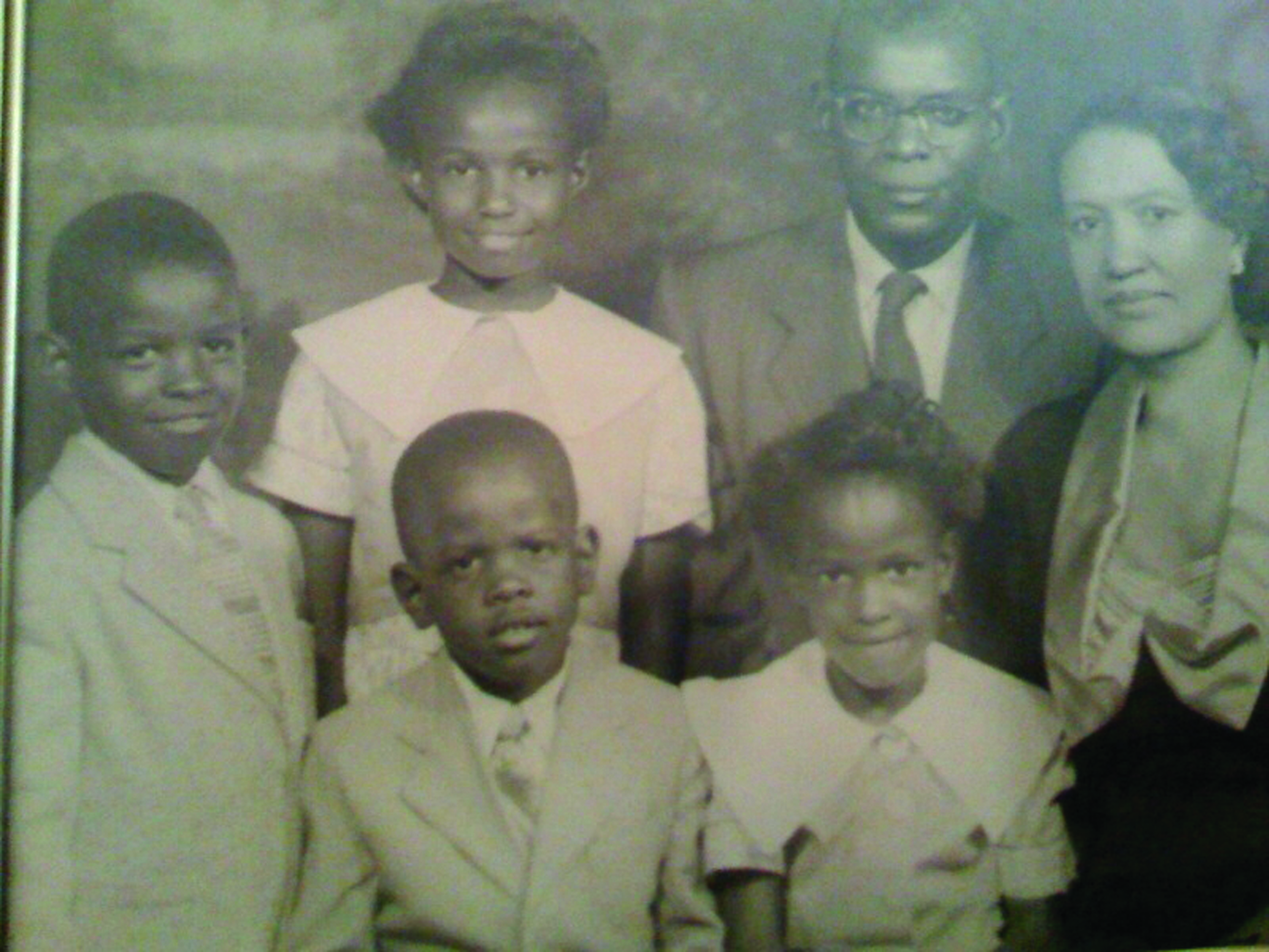

Childs Family, Washington, D.C., 1958

Collection of Faith Childs, New York

The most powerful and sustained vehicle for black self-representation and celebration did not require the cooperation of the media. Far from the stage sets of Hollywood and the advertising agencies of Madison Avenue, a simple, ever-present device was stoking a quiet visual revolution: the snapshot camera. As the popularity of increasingly inexpensive and easily accessible cameras swept across the nation in the early twentieth century, the images created by these cameras did for African Americans what a century and half of mainstream representation often could not: made visible the complexity of a people too often ignored by or erased from mainstream culture. |