UMBC professor of biology Suzanne Ostrand-Rosenberg found a box of faded letters that led her deep into her family’s history–and led scholars to fascinating new findings in Holocaust studies.

By Elizabeth Heubeck ’91

Suzanne Ostrand-Rosenberg’s mother Marianne came of age as a German Jew during the rise of Nazism and the beginnings of the Holocaust. But she said very little to her daughter about her family’s history during that trying period.

“Growing up in a house where you sort of knew something happened, though it was never discussed—it’s as if those years never happened,” says Ostrand-Rosenberg, who is now a professor of biological sciences and the Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Chair of Biochemistry at UMBC. Her voice trails off as she excuses herself to wipe away some tears.

But Marianne Steinberg Ostrand did have a story to tell her daughter (and others) about those difficult years. As Ostrand-Rosenberg cleaned out her parents’ home in Columbia a few years ago, sifting through drawers, cabinets, and closets and taking stock of a lifetime’s worth of family memorabilia, she spotted a worn brown cardboard box emblazoned with old-style German writing.

The box contained a stack of about 200 wartime letters written by family members, many of them from her grandmother, great aunt and great uncle to her mother. Most of them were dated between 1938 and 1941, after Ostrand-Rosenberg’s mother had left Germany and come to the United States.

More discoveries emerged as Ostrand-Rosenberg dug deeper. “Each day I’d find a whole new stash,” she says.

That correspondence and other documents are now seeing the light of day in a new book, Life and Loss in the Shadows of the Holocaust (Cambridge University Press), co-authored by Rebecca Boehling, a UMBC professor of history and director of the James T. and Virginia M. Dresher Center for the Humanities, and Uta Larkey, an associate professor of German Studies at Goucher College.

Though the story of Ostrand-Rosenberg’s family shares a great deal in common with other narratives of the persecution, exile and attempted extermination of Europe’s Jews in that era, it also holds many surprises and adds new shadings and nuances to the historical record of Nazi Germany and its Jewish population. (See “Between the Lines”)

And as the two humanities scholars helped to tease out the rich narrative contained in the biology professor’s family letters (and also in other family letters, diaries, and interviews with living relatives), the three women formed a close and unexpected relationship—with one another, and with the subjects of the book.

“I think [Boehling and Larkey] know more about my family than I do,” observes Ostrand-Rosenberg.

A Box of Letters

The first brown cardboard box of letters that she found held as many questions as answers about Ostrand-Rosenberg’s family history. But her family’s circumstances left her largely in the dark. Her 91-year-old father was preparing to move to a retirement community mere months after her mother had been placed in an Alzheimer’s care facility.

Feeling somewhat overwhelmed by her discovery, Ostrand-Rosenberg shared her findings with colleagues. Phyllis Robinson, a fellow professor of biology, knew Boehling from her work on UMBC’s Gender and Women Studies Coordinating Committee and suggested the historian as a possible resource. Boehling’s areas of academic research include the Holocaust, and she has written a book – A Question of Priorities: Democratic Reforms and Economic Recovery in Postwar Germany (Berghahn) – on the American occupation of Germany.

When Ostrand-Rosenberg and Boehling talked about the letters, it turned out to be fortuitous timing. Deborah Gayle ’02, M.A. historical studies, a trained archivist studying with Boehling, was seeking a meaningful thesis project. Gayle organized the initial set of over 100 letters, photocopied them on acid-free paper and then entered them into a database. To complete her historical studies master’s project, Gayle also prepared a narrative based on the English-language letters and her research on the Holocaust with input from Ostrand-Rosenberg.

Gayle’s work on the letters gave Ostrand-Rosenberg something tangible to share with cousins as far away as Chile and Israel. “When Sue shared the letters with her cousins, they decided they really wanted more,” Boehling recalls.

The cousins also dug out family letters in their possession from the same time period, and the aggregation of family information made Boehling consider writing a book based on the letters. But as she was deeply entrenched in a new study on denazification in postwar Germany, she hesitated to take on another book project by herself.

Enter Uta Larkey. Her husband, Edward Larkey, a professor of modern languages and linguistics at UMBC, had briefly attended graduate school with Boehling. The two scholars lost contact but later found themselves as colleagues at UMBC in 1989, at which point they co-organized a conference on German unification at the university and later team-taught a seminar on culture in Nazi Germany. Occasionally, Boehling socialized with Uta, a native of the former East Germany.

During one of those informal get-togethers, Boehling shared her interest in the letters. “When I talked to Uta about a possible book project, I was thinking out loud. She was starting to do Holocaust storytelling,” Boehling says. “We decided to do it [the book] together.”

Correspondence Course

Co-authorship on the project made sense, given that both women shared a professional interest in the Holocaust. But they did come to the project with different research perspectives and skills.

“Uta came to this project as a non-historian,” recalls Boehling. “She was teaching a Holocaust film and culture course. As a historian, I was learning to be a more creative writer, as she was learning to be more of a historian.”

Blending talents took time, but Boehling and Larkey worked carefully to create a book that would present the family’s personal history within its historical context.

“The voice [of the book] came together through many revisions. After quite a while, we could hear each other’s voice,” Larkey says. The materials from which the authors worked grew significantly as they dove into the project. The authors gleaned information from family diaries and journals; conducted interviews with living relatives; and re-traced the family’s footsteps in Altenessen, the German suburb of Essen where Ostrand-Rosenberg’s mother lived until she immigrated to the United States.

But the letters – personal, eloquent, and hand-written, sometimes several pages long – remained at the heart of the enterprise. “These were not just quick, email-type things. These were real letters,” says Ostrand-Rosenberg.

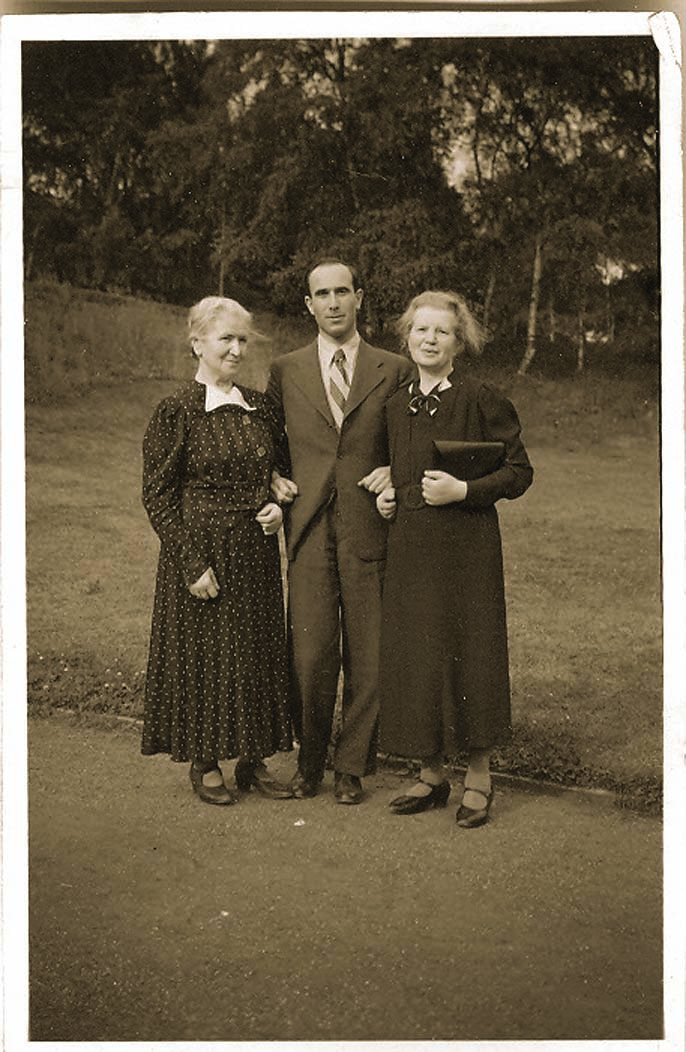

The vast majority of the letters were written between 1938, when Ostrand-Rosenberg’s mother emigrated from Germany, and 1947. There were scores of letters between her parents and correspondence between Ostrand-Rosenberg’s mother and her grandmother, Selma Kaufmann, her grandmother’s sister, Henny Kaufmann, and with her mother’s siblings: Lotti and Kurt.

The letters provide first-hand accounts of how the family was affected by the political unrest that entered their lives with the rise of the Nazi regime. They also detail the family’s fears about World War II and urgent negotiations over obtaining visas for family members to emigrate from Germany during the war. The letters also give insight into Selma and Henny’s experience as two of the first female business owners in a suburb of Essen (it was highly unusual in that era for women to own businesses), as well as the eventual closure of their business as the Nazi regime passed more and more laws discriminating against Germany’s Jews.

Sorting through the massive amount of correspondence was an enormous task. Ostrand-Rosenberg, Boehling, and Larkey copied the letters together, and collectively built upon the database that Deborah Gayle had begun.

“We had some 600 letters to work with,” Boehling recalls. “One spring break, (Uta and I) spent the whole time going through the letters.”

“We stood at the copy machine at UMBC for hours, copying letters,” Larkey recalls.

Not an Ordinary Research Project

The grunt work of collecting, sorting and copying letters – and pursuing their context through other avenues – yielded a useful and unique contribution to Holocaust scholarship. But it also became a richly personal and moving experience for the researchers and for the woman who first set them on the trail of her family history.

“When I would read a particularly emotional letter, I would find myself in tears,” acknowledges Boehling, who grew so close to the book project she said she began having dreams about its subjects.

A number of the letters are indeed heartbreaking, such as this one that Ostrand-Rosenberg’s grandmother Selma wrote to a friend from a so-called “communal camp” in Cologne in 1942:

Now our fate has also been decided. We will have to move into the barracks on 18 February. I am hoping for a little reprieve (Galgenfrist), but all living quarters have to be vacated by the end of the month. You can imagine our mood, I don’t want to say more about that, but hope that now one won’t lose the nerve to survive this time. Only the hope that it will get better for us…

The research project also galvanized and inspired Ostrand-Rosenberg’s family. Gideon Sella, Ostrand-Rosenberg’s first cousin and a photographer in Tel Aviv, photographed Selma’s letters, then ripped them apart and artistically arranged them into an oversized collage.

Larkey felt “overwhelmed” when Sella shared his artwork—both by the powerful statement it made, and by seeing the handwriting that she had worked with so extensively. Fittingly, the cover of the book contains a piece of Sella’s collage.

Ostrand-Rosenberg feels gratitude at having the story that began with a brown cardboard box told at last. “I will be forever indebted to Rebecca and Uta for giving me what happened,” she says. “I never would have known it otherwise.”

Boehling also sees the book not only as a scholarly endeavor, but as a recovery of family memory. “I think the book won’t be just for her [Ostrand-Rosenberg], but for her children and grandchildren, as a way of getting to know that part of the family that none of them ever shared.”

Tags: Summer 2011