Diana Zeiger ’01, biochemistry is an editor and writer for the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. She is also a published poet. UMBC Magazine asked her to reflect on the areas in which her two passions overlap.

A poet and a scientist walk into a bar. Sounds like the setup for a terrible joke, doesn’t it?

I can tell you, however, that they’d actually have a lot in common.

Exploring these commonalities has been at the center of my professional life. I took a bachelor’s degree in creative writing at Johns Hopkins University, where my main interest was poetry. After graduating, I worked as an editor at a small poetry press for a few years. I enjoyed my job but eventually began to find it increasingly unfulfilling.

As a child, I was interested in science but set that interest aside as an undergraduate. So I attended UMBC to start on the path to medical school, but the opportunity to do undergraduate research led me to switch directions and pursue a doctorate in oral and craniofacial sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. (Think of it as a Ph.D. from a dental school.)

Even though I chose to pursue a career in science, my interest in writing never disappeared. In fact, my love of research somewhat naturally led me to seek out what the two disciplines share in common.

One thing poetry and science have in common is a love of questions. Specifically, both ask small questions that explore larger, deeper issues.

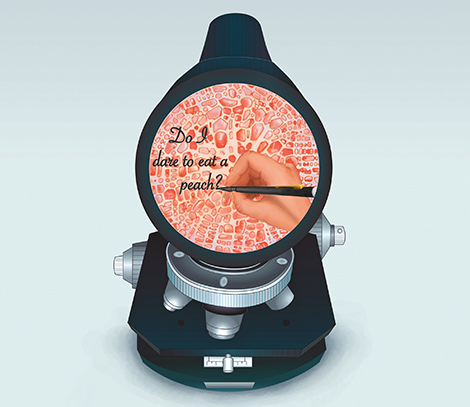

Take one of the most famous questions in modern poetry: “Do I dare to eat a peach?” The narrator of T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” isn’t simply pondering his choice of snack. This timid fellow is contemplating the loss of his youth and the inevitable decline of his vitality and questioning whether he is capable of expanding his ever-diminishing world. Similarly, when a biochemist asks whether a particular molecule interrupts a given signaling pathway, the impact of the answer may be as large as: “Can this drug stop the progression of cancer?” Both poetry and science embrace small questions to unlock grander concepts.

Precision is another shared quality of poetry and science. Poetry is nothing if not economical; when writing poetry in forms as exacting as a sonnet or a villanelle, not a syllable can be wasted. Each word must be chosen carefully for qualities of sound and its meaning. Precision is equally essential to any scientific endeavor. Instruments must be used with meticulous care, quantities measured exactly, and actions performed and recorded in such a way that they can be perfectly duplicated. Without precision in the laboratory, science could not advance.

Precision is another shared quality of poetry and science. Poetry is nothing if not economical; when writing poetry in forms as exacting as a sonnet or a villanelle, not a syllable can be wasted. Each word must be chosen carefully for qualities of sound and its meaning. Precision is equally essential to any scientific endeavor. Instruments must be used with meticulous care, quantities measured exactly, and actions performed and recorded in such a way that they can be perfectly duplicated. Without precision in the laboratory, science could not advance.

Once I completed my introductory science classes and began performing more advanced research, I became aware of another parallel between poetry and science less obvious to those people outside the laboratory: both disciplines require interpretation.

As early as middle school, students are taught that poems can be appreciated in multiple ways, and that the words and phrases comprising them can have layers of meaning. The language of a poem may be melodious and tell an interesting story, but there is often more to learn by digging a little deeper. Enjoyment of poems can be enhanced by knowing – or even investigating – a poet’s biography or a poem’s historical context. Efforts to identify the “Dark Lady” of Shakespeare’s sonnets has led to seemingly endless hours of debate, yet this investigation has also enriched our knowledge about – and deepened our appreciation of – these extraordinary poems.

Debate is also an important part of doing science, though this aspect is not something taught in most schools at an early stage. In primary and secondary schools, the main thrust of science education is learning facts. Even laboratory classes typically center around tried-and-true experiments where in which the aim is to achieve preordained results. However, this early education is merely intended to lay a foundation, as I found out when I embarked upon my own research career.

Professional researchers gather all the available knowledge on a topic and then interpret it to generate new hypotheses. Once tested, the new information yielded must then be interpreted again in order to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis. Facts are an indispensable part of science, but pursuing the meaning of these facts within the context of what is already known is what truly enables us to move science forward.

Neuroscience researchers have used poetry as a tool to explore how the brain processes language and sounds; the composition of poetry has also been studied in an attempt to discover the source of creativity itself. Conversely, thanks to their complex, often abstract use of words, poems about scientists and science reveal facets of their subjects that the straightforward language of essays and encyclopedias cannot do. Ultimately, it seems that science and poetry not only have a great deal in common, they also can serve to illuminate the best aspects of each other.

Tags: Diana Zeiger, Summer 2016