Making assumptions is a habit of life, a way to speed up decisions. Sometimes these mental short-cuts, however, lead us astray.

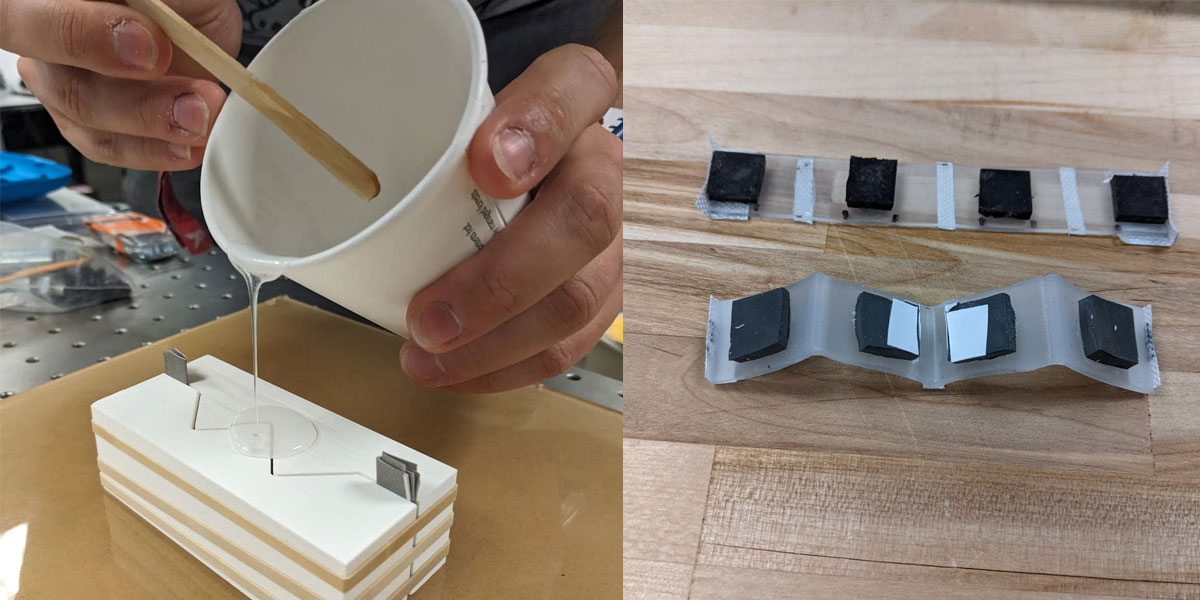

Such was the situation when Lorenz Kopp, an engineering master’s student at Germany’s Regensburg University of Applied Sciences who was visiting UMBC this fall for a 50-day exchange project, assumed the ovens in the U.S. lab he was working in would use the Fahrenheit temperature scale. He filled a mold with a plastic-like gel the group was using to make flexible accordion-shaped structures, put it in the oven to set, and sat back.

“And then I started to smell burning,” he says, with a smile. The ovens were in fact operating in Celsius, and he had set the temperature too high.

Kopp came to the U.S. with fellow Regensburg student Björn Michelmann to work with mechanical engineering professor Paris von Lockette. Their project was part of a bigger assumption-questioning enterprise—in particular probing the behavior of materials called soft magnets.

Soft magnetic materials tend to be metals that easily respond to (become magnetized in) the presence of a magnetic field, but go back to “normal” when the field is removed. This is in contrast to hard magnetic materials, which can be permanently magnetized. A typical fridge magnet is an example of a hard magnetic material, while a piece of iron is an example of a soft magnetic material.

Engineers are interested in magnets as a way to wirelessly control robots, but soft magnets are often assumed to offer a less versatile range of movements for these applications than hard magnets.

For about seven weeks during the fall semester, Kopp and Michelmann set up and ran a series of experiments putting some of these assumptions to the test. They designed accordion structures made from a flexible plastic-like material and embedded either soft or hard magnets in the accordions’ pleats. They then recorded how the structures folded or unfolded when exposed to magnetic fields. Early analysis of the results hints that the soft magnets may offer more versatility than initially assumed.

“It was great working with Lorenz and Björn. They were exceptionally productive,” von Lockette says. “We got interesting results and we’re working to write them up in a paper.”

Soft magnetic materials are appealing to engineers because they are cheaper and more biocompatible than hard magnetic materials, and also require less energy to be magnetized and demagnetized. If the group can demonstrate novel ways to get extra degrees of control over their movement, it could open a host of new applications, including in robots that assist in surgery or devices that are implanted in the human body to deliver drugs, monitor diseases, or substitute for the function of lost or damaged organs.

An international collaboration

Kopp and Michelmann got the opportunity to visit UMBC through funding by the German Academic Exchange Service. Their advisor at Regensburg University of Applied Sciences—Mikhail Chamonine—knew von Lockette through the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and together they arranged the details of the visit with the help of the Office of International Students and Scholars at UMBC. Chamonine specializes in the physics of electromagnetic fields, and his lab in Germany performs many experiments with rubber-based soft magnetic materials. Von Lockette has developed his career around turning science insights about magnetically active soft materials into new applications and devices. The area of magnetic control of robots was a natural overlap.

While Kopp and Michelmann spent plenty of time in the lab during their visit, they also had chances to explore the areas surrounding UMBC on weekends. They visited the National Aquarium in Baltimore, took in a Raven’s football game, and drove to Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. They also enjoyed campus life, attending Homecoming weekend in October and regularly visiting the Retriever Activity Center to work out.

Michelmann says it was eye-opening to experience life on a U.S. university campus. “In a lot of U.S. films, there are fraternities and sororities with houses where they party every night. But I learned that stereotype doesn’t apply to UMBC.” He says he was pleasantly surprised by the variety of activities on campus, from sporting events, to tabletop games, to events such as bingo and craft nights organized by the Student Events Board.

Advancing science and technology

Von Lockette says he hopes to continue the collaboration with Regensburg University of Applied Sciences, and to arrange trips for UMBC students to visit Germany in the future.

Kopp, Michelmann, von Lockette, and Chamonine remain in touch as they write up the results of their experiments. When they noticed some unexpected behavior of the soft magnet accordions, von Lockette says he found himself thinking back to discussions he had with Chamonine about the importance of what are called demagnetizing terms in equations describing the magnetization of materials. The terms are affected by the geometry of the material and explain, for example, why when you put an iron nail in a magnetic field, it is easier for the nail to magnetize along its length, rather than perpendicular to it.

The researchers are testing whether they can explain the behavior of the soft magnets they tested—and the difference from the hard magnets—using demagnetizing field calculations. A better understanding of the behavior could guide future experiments trying to demonstrate greater versatility of movements and finer control.

“We’ll experiment with different materials and different geometries. We’re wondering: If we apply this field, what can we make it do that we didn’t think it could do?” von Lockette says.

Von Lockette has a history of getting fellow researchers to consider the usefulness of materials they may have overlooked. Earlier in his career, he published a paper demonstrating the potential of a new type of magnetically active material—in that case made with hard magnets.

“That was my first big splash,” he says. Now he’s happy to give soft magnets their due too, while also encouraging a new generation of researchers, including Kopp and Michelmann.

Chamonine is also pleased with the work of his students. “They are working to get the results published, which is not typical for a short project,” he says.

Beyond pushing the assumptions of what could get done in the lab in seven weeks, Kopp and Michelmann also enjoyed the typical world-expanding experience of international travel. “It was not only the science,” Chamonine says, “but they also had a chance to stay in the United States. I think for them it was absolutely an exciting moment in life.”

Tags: COEIT, International, MechE