UMBC alumni work to preserve and present history for broad audiences in Maryland and beyond.

By Max Cole

UMBC’s history department is the only one in Maryland that offers a graduate track in public history. Students who take courses in public history learn that it is a unique profession that requires a unique approach to research and interpretation. Each course creates opportunities for students to engage in work on real projects with real partners, which in turn helps prepare them to enter the workforce upon graduation.

“Public history is a form of public service,” says Denise Meringolo, an associate professor of history at UMBC and director of the public history program. “Public historians help create historical understanding by sharing authority and inquiry with a variety of partners.”

“At UMBC, graduate students in public history develop a portfolio of work, produced in class and in internships that demonstrates they have a marketable set of skills, most importantly including experience in community-based public history practice.”

UMBC students who go into public history careers understand the importance of rooting their work and research in the communities they serve. They preserve and present history for broad, non-academic audiences, and they strive to relate historic objects, materials, sites and places to everyday people to make them understand their significance and value. Above all, they have an appreciation for what they do and a passion for history that often starts at a young age.

Smelling the Campfire

When Jim Bailey was seven years old, he witnessed his first historical re-enactment at New Market Battlefield in Virginia. He remembers it as the moment he decided he wanted to work in public history.

When Jim Bailey was seven years old, he witnessed his first historical re-enactment at New Market Battlefield in Virginia. He remembers it as the moment he decided he wanted to work in public history.

“A living historian let me try on his coat and hold his musket. I could see the camps and I could smell the campfires,” remembers Bailey. “I remember as a child just being enthralled by everything I was hearing, seeing and smelling.”

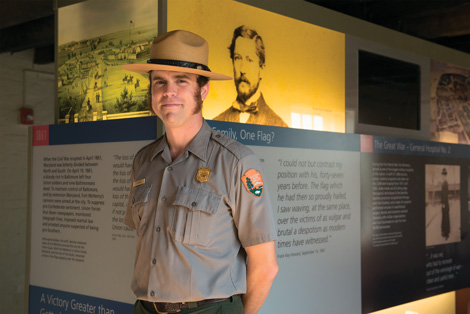

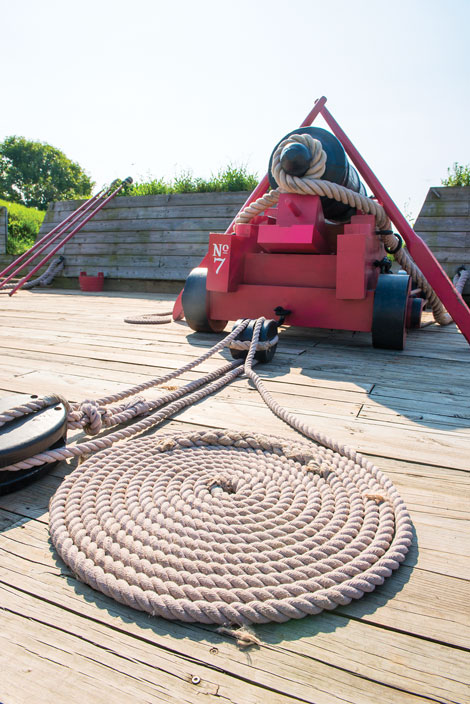

Bailey ’03, history, and ’08 M.A., historical studies, now works as a park ranger and volunteer coordinator at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. As park ranger, Bailey presents interpretive programs, serves as historic weapons supervisor, and coordinates the living history volunteer program with the Fort McHenry Guard.

As a student of history and having grown up in nearby Catonsville, Bailey understands the significance of Fort McHenry to Baltimore and American history, and each day on the job he interacts with visitors from across the globe.

As a student of history and having grown up in nearby Catonsville, Bailey understands the significance of Fort McHenry to Baltimore and American history, and each day on the job he interacts with visitors from across the globe.

“In an age when we are addicted to our smartphones and everything moves so quickly, we have visitors here that don’t necessarily understand the War of 1812, let alone the Battle of Baltimore,” Bailey observes.

“Two hundred years ago is incredibly remote,” he continues, “so how do you engage people in a meaningful way and make a connection? That’s what interpretation is all about.”

Bailey says if visitors can think of the War of 1812 and its impact on American history, he has done his job.

“When you’re walking up on the fort walls and you begin to contemplate what happened there, it’s powerful. When you start to hear fifes and drums on the parade ground, and see soldiers marching and sergeants shouting out commands and can see them drilling just as they did 200 years ago…the fort becomes alive like it wasn’t 20 minutes ago. Those are things that stay with you for the rest of your life.”

Family Ties

Many UMBC history alumni have their own personal story — something they can point back to as being a stepping-stone for where they are now.

For Robert Bennett, it started with a research paper about a historical aspect of his family he produced as a student at UMBC.

Bennett ’12, history and ancient studies, is executive director of the William Brinton 1704 Historic House in West Chester, Pa. He landed the job through his research paper on the Bennett family, in which he discovered he was descended from English Quakers who helped colonize Pennsylvania in the mid-1680s. In the course of his research, he discovered that the descendants of this family owned and operated a historic house and museum dating back to 1704 in West Chester.

Eventually, Bennett found that his seven times great grandfather built the housewith his brother-in-law in 1704.

“Whenever I come here to the house, it makes me think about my seven times great grandfather and grandmother,” says Bennett. “It’s very personal for me. When I come here, it’s like coming home.”

As executive director, Bennett cleans and maintains historic objects at the home, maintains records, organizes volunteers, presents tours and coordinates events throughout the year. In all his work, he tries to make visitors understand his strong, personal connection to the historic home with the goal of having it resonate in their own lives.

“UMBC taught me that if you can find the personal connection or the human touch in a historical document, object or artifact, then you can relate to it better,” says Bennett. “If you can relate to it, you can relate it to others in that way.”

Bringing History to Life

UMBC’s history department teaches students research, interpretation, communication and writing skills, all of which are necessary to be a successful public historian.

UMBC’s history department teaches students research, interpretation, communication and writing skills, all of which are necessary to be a successful public historian.

Allison Seyler combines all of those skills in the day-to-day work she does as a research archivist at the Maryland State Archives.

Seyler describes her job as having three tiers: data mining, research and education. Seyler ’10, history and French, and ’12 M.A., historical studies, works on the grant-funded Legacy of Slavery in Maryland project. Focusing on five counties on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Seyler researchers newspapers, advertisements and government records from the 19th century to create biographical sketches or case studies on slaves, slave owners and fugitives living on the Eastern Shore.

“It’s all about these individual stories we are rediscovering,” says Seyler. “They didn’t go anywhere. These stories are there. We just have to bring light to them. We illuminate these people’s struggles and their experiences because they’re worthwhile. They have value. They’re important to the American story and the Maryland story.”

In addition to using her research and writing skills to produce case studies, Seyler presents her findings to a variety of audiences: teachers, students at all levels, and even descendants of Eastern Shore families who have lived there for centuries.

“This is the human experience,” explains Seyler. “Who is to say that’s not important?”

When the Light Bulb Goes Off

While many alumni who are now working as public historians thoroughly enjoy their jobs, it is important to understand how much of the work can be a time-consuming challenge, especially in a managerial role at a national museum.

While many alumni who are now working as public historians thoroughly enjoy their jobs, it is important to understand how much of the work can be a time-consuming challenge, especially in a managerial role at a national museum.

When Alice Donahue first started working at the National ElectronicsMuseum in Linthicum, her first job was to project manage the opening of a new gallery about the introduction to concepts and principals of electronics.

“When I came in, I had to literally cut half the words [for interpretive displays],” says Donahue ’05, history, and ’08 M.A., historical studies. “When you take historiography at UMBC, you need to be able to reduce the argument of a 400-page book to one page. That skill definitely translated to exhibit writing.”

“When I came in, I had to literally cut half the words [for interpretive displays],” says Donahue ’05, history, and ’08 M.A., historical studies. “When you take historiography at UMBC, you need to be able to reduce the argument of a 400-page book to one page. That skill definitely translated to exhibit writing.”

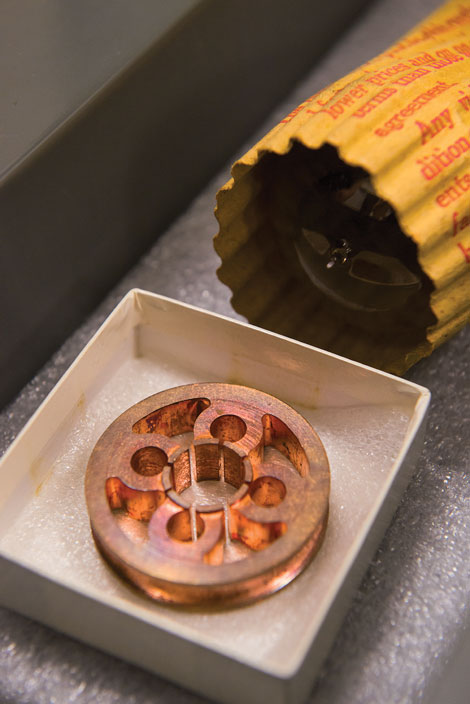

As the museum’s assistant director, Donahue manages the museum’s collection and volunteer program. She brings in new objects, organizes and cleans objects on display, and maintains mountains of paperwork on them noting where they came from and why they are important.

The museum helps people understand how electronics and communications have evolved, which makes the job worthwhile for Donahue.

“Public history is about making history that people care about. How do I pick which words people are going to care about and what about this history makes them understand themselves and their experience better?” says Donahue, describing the challenges of her job.

“When the light bulb goes off and people realize they knew more than they thought they did and the world is suddenly bigger and their role in it is bigger…it cements their place in history and that is what I really enjoy.”

It’s Not Just About the History

As demonstrated by several UMBC alumni working at International Mapping Company in Ellicott City, one doesn’t necessarily need to major in history to pursue a career in the public history field.

International Mapping creates interactive maps, applications, signage, videos andother materials to enhance the user’s experience while visiting historic sites, national parks or even studying history in the classroom.

“We specialize in displaying geographic information for people so they can better understand it,” explains Dan Przywara ’94, geography, and director of sales and marketing at the company. “It’s one thing to read a word and try to visualize what happened. It’s another thing to actually see something and be able to comprehend it from that image.”

International Mapping has worked on projects from Maine’s Acadia National Park to Harpers Ferry National Historic Park and beyond. Twelve employees of the company are UMBC alumni representing majors from geography and visual arts to computer science. While much of the work involves advanced technical skills, employees still need to have strong research, writing and analytical skills, all of which are the foundation of what goes into producing compelling public history.

“With a historical map video, I have to research historical events in order to map them properly, so it combines a lot of other skills – both technology and general research knowledge,” says Kevin Lear ’85, geography, who is senior project manager at International Mapping and recently completed a video history project on the Korean War.

“We know the skills that UMBC alumni have when they get here can transfer to our company,” explains Przywara. “With the range of skills that we require, UMBC provides that.”

People and Community

Graduates of UMBC’s public history program and other related majors are prepared to enter the workforce with a full complement of skills that will enable them to contribute to preserving and presenting history for decades to come.

Whether it’s creating digital maps, presenting re-enactments or leading tours, alumni are prepared for a variety of jobs in public history. However, there is one common thread that is taught at UMBC that carries over into the everyday work: it’s all about people and community.

“It is truly crucial for public historians to understand that the questions guiding their research and the interpretive products they produce must be rooted in the communities they serve,” says Denise Meringolo. “Otherwise, they will be insignificant and unimportant.”

The desire to serve the community is evident with public history alumni, and perhaps more powerful is the fact that many of them wish to continue giving back.

“As a graduate of the program, I thought it was so enriching and well put together, I want to stay involved in that community,” says Alice Donahue. “We want to keep giving back. We got so much from the program, and we want to continue to help the next generation to keep getting that.”

Tags: Fall 2014