A Date with Darwin

Forgive Sandra Herbert if she’s a bit exhausted as 2009 comes to a close.

Herbert, a professor emerita of history, is one of the world’s foremost authorities on the work of Charles Darwin, whose theorizing on natural selection and evolution revolutionized the course of scientific thought. And 2009 held not one but two significant Darwinian anniversaries: the 200th anniversary of his birth (on the same date, February 12, 1809, that Abraham Lincoln was born) and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his classic text, On the Origin of Species.

The “Darwin Year” saw Herbert giving lectures at venues including the Library of Congress and participating in events from Stockholm to Cambridge – the university where Darwin studied and later taught as a fellow at Christ’s College. Herbert was a distinguished visiting scholar at Christ’s College in the 2006-07 academic year, where she helped plan events for the Cambridge celebration and worked in the Darwin archives.

“The invitations started coming in 2005,” Herbert says. “It really was a bigger deal than we expected.” Herbert has edited groundbreaking scholarly editions of Darwin’s working notebooks – including the famous “Red Notebook,” which he started after his voyage to the Galapagos Islands, and in which he worked through early versions of evolutionary theory.

Her recent work on Darwin has excavated his early work as a geologist. Her book Charles Darwin, Geologist (Cornell University Press, 2005) not only unearthed Darwin’s passion for studying and theorizing about geology, but also drew clear links between that early work and his later revolutionary work in biology.

The biggest connection, says Herbert, was how Darwin and others built theories from the diligent work of 18th and early 19th century geologists to construct a geological record of the planet through analysis of various layers (or “strata”) of the earth’s soil and rock.

“By 1850, it was clear that if you go through the strata of the earth’s crust, you’re seeing the history of life on the planet,” she says. Geologists of that era “became very interested in when different kinds of life enter into the fossil record. And they knew that mammals came in much later than, say, fish…. So quite apart from the theory of evolution, there was already a growing understanding about the history of life on earth. And Darwin just presumed on that. He built on that. And offered an explanation as to why this was so. Why some species had become extinct and why others had replaced them. And he posited that newer species had come from the older ones.”

Herbert says that celebrating a Darwin year not only focused attention on the English scientist’s work, but also helped attract funding for a variety of Darwin-related projects, including an expedition made by Herbert and other American and British scholars – mainly geologists – to the Galapagos Islands to retrace the geological work that Darwin had done there on the voyage that changed science and history.

The journey resulted in a paper published earlier this year in Earth Sciences History, and Herbert says that it demonstrates what historians and geologists could accomplish working together as teams. “It was a lot of fun,” she says. “Lots of the other work I have done was manuscript work. Transcribing. It’s things you do like a monk. This was more congenial. People with different areas of expertise and knowledge coming together to answer each others’ questions.”

The Science of Salt

Hours before a snow storm roars in, trucks hit the road to spread a coarse form of table salt on highways and streets. Salt is a cheap and effective way to keep roads clear. It lowers the freezing point of the water on the road, creating brine which does not crystallize as the snow falls.

Some 20 million tons of sodium chloride are spread on roads every winter. But what happens to all that road salt when the storm passes? It is washed into the soil, the water table and eventually our drinking water. Chris Swan, associate professor of geography and environmental systems, studies the lingering effects of road salt. His preliminary findings are surprising.

The chloride in sodium chloride is the main problem, Swan says. Sodium atoms tend to stick to whatever is around them; chloride goes into the water. Vestiges of chloride from winter deicing can be traced well into the spring in soil samples, in the storm drain system, and in natural bodies of water. Swan’s lab also found increasing amounts in Baltimore’s drinking water. While the amount still is far below dangerous levels, the water eventually may become undrinkable.

To measure possible effects in nature, Swan and a graduate student, Robin Van Meter, put com-mon grey tree frogs into a 500-liter artificial pond and added salt in varying concentrations.

Amphibians are believed to be extremely sensitive to salt, so the researchers expected the frogs would get easily stressed and perhaps sicken, die, or become dwarfed and stunted. The reverse happened, Swan found. They grew from tadpole to adult frog a few days earlier and seemed to be a bit larger.

This finding does not mean the frogs are thriving in salt, Swan emphasizes. “We don’t know what’s going to happen once they are adults,” he says. “There could be less genetic variability; they could produce fewer eggs, natural selection could occur at a faster rate.” Their larger size might make them easier prey for natural predators, for instance.

Swan adds that salt’s effects on other creatures in a salt-tainted pond were more predictable. Tiny invertebrates near the bottom of the food chain called zooplankton die off in the salt, triggering both an increase in algae and a disruption of the food chain for other creatures who dine on them.

Despite these findings, Swan is not yet ready to endorse a ban on road salt. Authorities using it are generally responsible, he observes. But he emphasizes that the long-term effects of road salt are largely unknown.

“I don’t say salt is bad – just yet,” Swan insists. “But if you put value on ecological communities, what you are going to see [as a result of road salt’s use] will be different.”

Does Swan put salt on his own sidewalk at home in Columbia? He does. But he says that he makes sure he doesn’t overdo it.

Sign of the Times

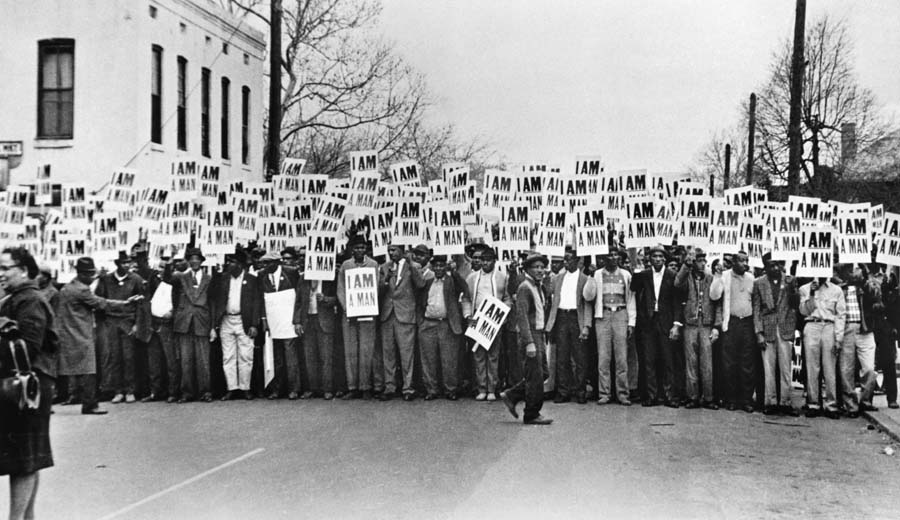

UMBC’s Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture (CADVC) has received a $400,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The grant will fund For All The World To See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights, an exhibit curated by Maurice Berger, a senior research scholar at the CADVC, on the role of visual images in the battle for civil rights in the United States.

The exhibit will appear at New York’s International Center of Photography in May and at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in June 2011 before concluding its tour at the CADVC in fall 2012. Yale University Press will publish a companion book to the exhibit.

Creating a Smarter Web

Imagine entering a conference room for a meeting. Your cell phone exchanges virtual business cards with the phones of everyone else in the room. Your laptop automatically uploads slides for your presentation directly to a projector on the table – without the aid of a thumb drive.

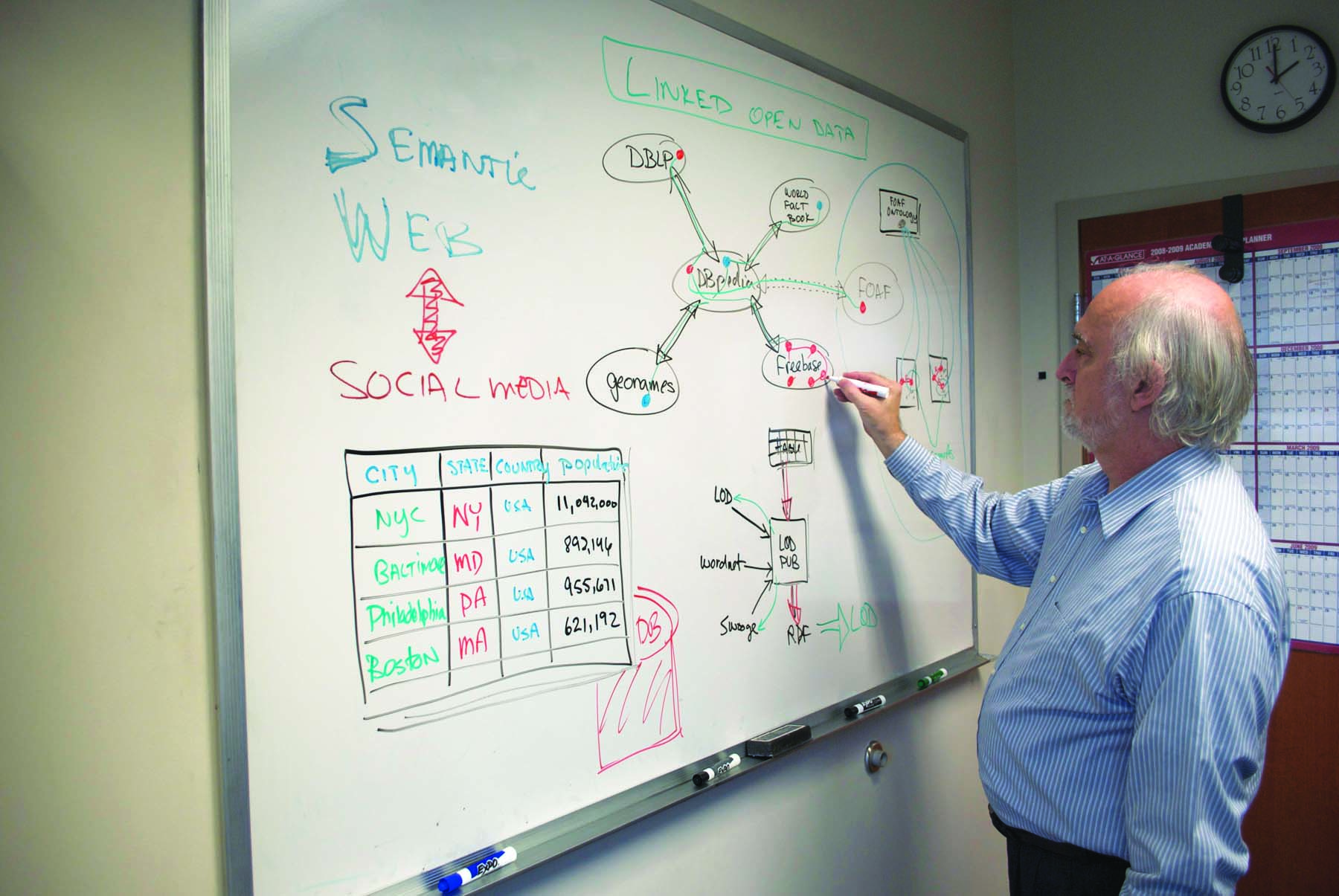

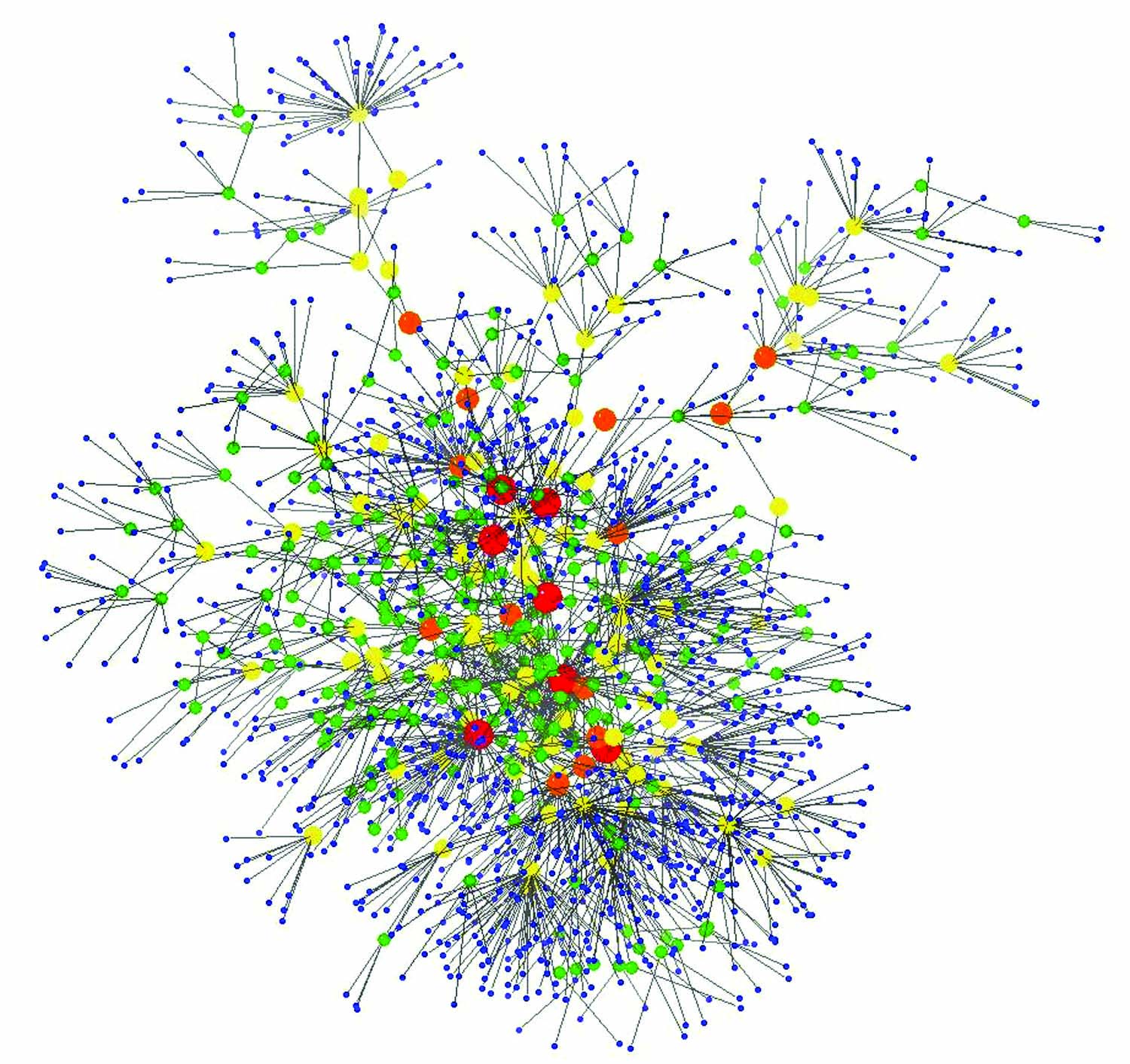

If UMBC computer science professor Tim Finin gets his way, a concept dubbed the “Semantic Web” will make such meetings a staple of the future.

A professor at UMBC since 1991, Finin has long been an esteemed researcher in the field of computerized artificial intelligence. Last year, the Computer Society of The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers selected him to receive its esteemed Technical Achievement Award.

He began his explorations into artificial intelligence, or AI, as a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the late 1960s, when asking computers to recognize human speech and play chess were the frontiers. Those challenges have long since been conquered, but the search for smarter and better artificial intelligence continues. The newest frontier of AI seems to be in better harnessing the power of computer networks.

“When the Web happened in the mid 1990s it surprised everyone at how profoundly this changed the way we could exchange information,” Finin says. “There seems to be something special about the way the Web works and the way people connect to it.”

When Sir Tim Berners-Lee first thought up the idea of a Web of hyperlinked pages, he had computers, as well as people, in mind. Why couldn’t computers share their information as easily as cooks sharing recipes on Facebook? Berners-Lee called this concept the “Semantic Web.”

People view Web sites with computers, and can understand and differentiate between the sorts of data that these sites display. Computers do not. The text of a name and the text of an address, for a computer, are simply strings of data. The Semantic Web is the effort to annotate all data in a consistent way, so it can be understood by computers in such a way without additional boxes or schematic frames.

“Just as the Web made people more intelligent, the Semantic Web would make our computer programs more intelligent, because they would find the same information in a form that they could ingest and understand,” Finin says.

Finin has led a number of different projects at UMBC that demonstrate how the Semantic Web would work in real life, including a concept called “intelligent spaces” that would allow direct information sharing via portable devices. “The idea with these intelligent spaces is to have the devices be active in trying to understand who is in the room, and why they might be there,” he says.

Will the Semantic Web snowball catch on like the first Web did? “It’s totally impossible to predict how these things unfold,” he says. But if it does, we’ll have Finin’s work to thank.

Let it Snow

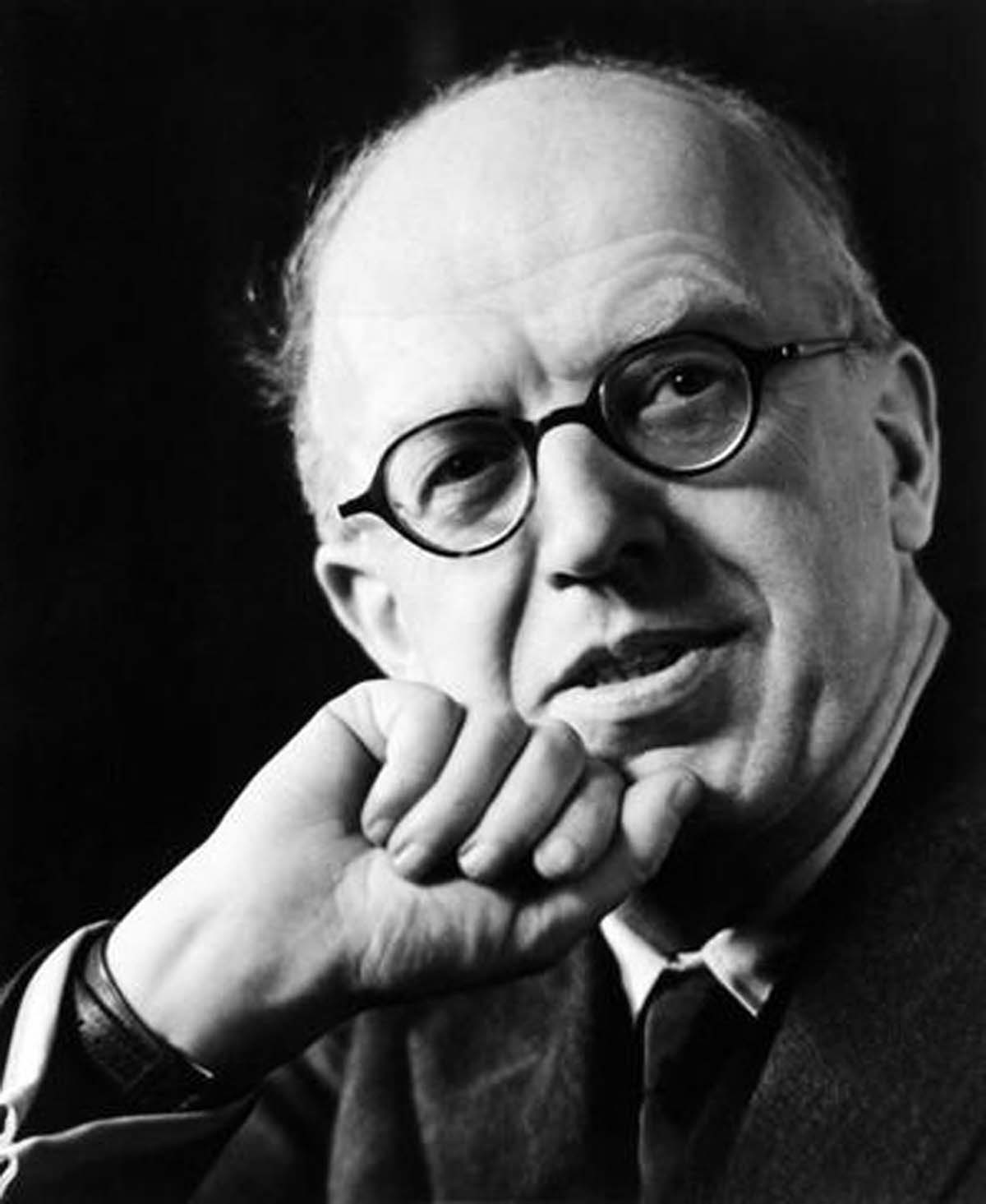

On May 7, 1959, English novelist C.P. Snow (left) gave a lecture at Cambridge University, “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution,” that has helped define debate on the relationship between branches of human knowledge – especially the sciences and literature – for five decades.

As Stefan Collini notes in his introduction to a new edition of the lecture published by Cambridge University Press to celebrate its 50th anniversary, Snow’s essay was a limited and imperfect formulation of the two cultures he described. His definition of “literary intellectuals” was narrowly drawn and quite specific to England. And Snow’s optimism in science’s ability to solve human problems has been undermined by a multiplicity of ethical concerns.

Yet the essay deftly captured a specific and continuing rupture between researchers in the so-called natural and physical sciences and their colleagues in the arts and humanities – as well as the awkward straddle of those in the social sciences between that divide. Snow’s notion of two cultures has been used to help explain the decline in the prestige of the humanities and the increasing corporate and governmental presence in research universities. But Snow’s most enduring and useful concept is that of a mutual linguistic and conceptual incomprehension across the lines he drew 50 years ago.

This past autumn, UMBC’s Human Context of Science & Technology Program (HCST) and the university’s Dresher Center for the Humanities created a series of five lectures – and an introductory level class – celebrating and critiquing Snow’s essay. The lectures drew prestigious scholars from as far afield as the United Kingdom (Cardiff University and the University of Warwick) to discuss and debate the influence of Snow and his ideas on the history of knowledge, cultural politics and climate change.

The result of the lecture series, says Joseph N. Tatarewicz, director of the university’s HCST program, was the stimulation of a campus-wide discussion that was “beyond my expectations.” He observes that “competition for scholars during this 50th anniversary year was intense, and we managed to attract some of the best scholars from a variety of disciplines and institutions to visit UMBC. Also gratifying was the diversity of the audience – humanists, social scientists, physical and natural scientists from on-and-off campus were there for all the events.”

Rebecca Boehling, director of the Dresher Center, says that the lecture series “seemed a good way to address head-on both differences between the humanities and the sciences with regard to the visibility of their research, as well as to reach out to the sciences – so that UMBC faculty and students outside the humanities might become more aware of both the historical dimension of these tensions.”

“Ideally,” continues Boehling, “neither faculty in the sciences and technology nor those in the humanities work in ways that are immune to the approaches of the others’ field. We share many similar concerns and goals in our research.”

Tatarewicz concurs, and notes his current work interviewing founding faculty for a history of UMBC has pointed to a convergence of ideas and disciplines in the university’s first years. “There wasn’t enough faculty for full departments of everything,” he observes, “so the university began in an atmosphere of interdisciplinarity and extreme collegiality. During this series, it felt like we had resurrected some of that early spirit.”

****

Header image: Sanitation workers assemble in front of Clayborn Temple for a Solidarity March in Memphis, TN.

Tags: Winter 2010