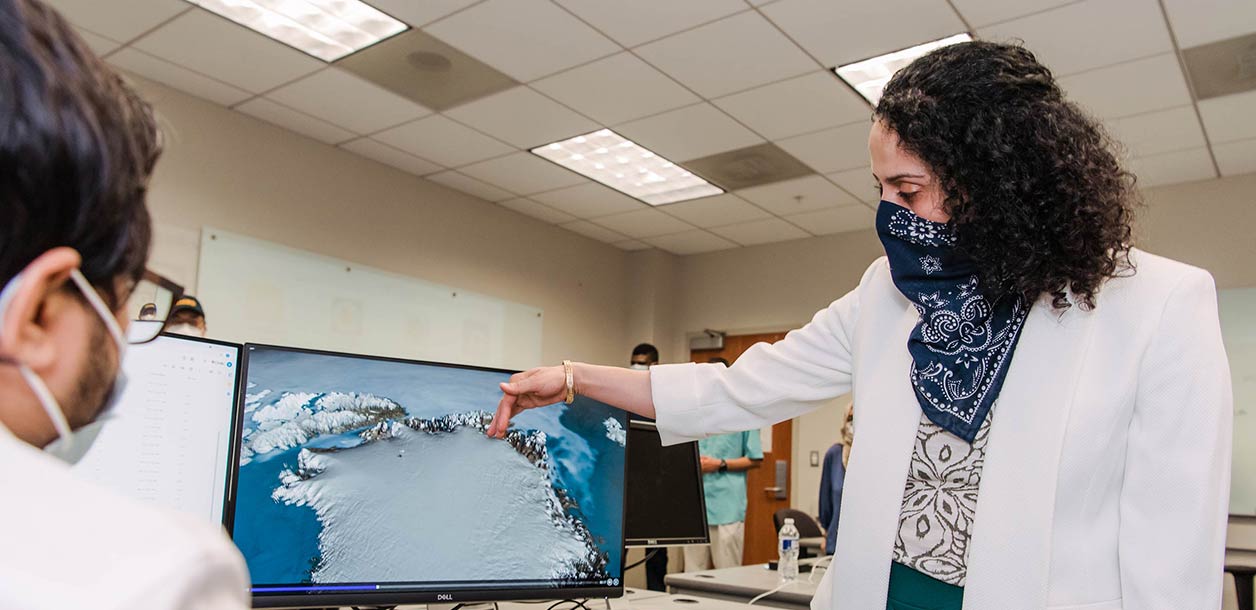

Natural disasters leave layers of industrial and economic damage in their wake—not to mention loss of life. In order to better combat the next unforeseen event, data is collected immediately after floods, hurricanes, and other weather-related tragedies. But when Maryam Rahnemoonfar, associate professor of information systems, was in graduate school, she had to cull through this data manually. Eager to combine her interests in civil engineering, remote sensing, and computer science in a meaningful way, Rahnemoonfar began developing an algorithm that could automatically assess and understand the post-disaster data.

Along with her colleagues, Rahnemoonfar began working with the Humanitarian Robotics and Artificial Intelligence at Texas A&M University, where she was faculty before coming to UMBC. Rahnemoonfar explains that various types of robots including unmanned aerial vehicles and robots on the ground and on water are used to collect data, but the data needed to be analyzed closely.

“The data collected is not AI ready,” Rahnemoonfar explains, noting that in order to make the data about natural disasters more useful, it needs to be annotated and trained. The data helps determine the level of damage caused by these events, including what type of response team is needed and the immediacy of the need.

The next step, she says, is to develop an AI and machine learning algorithm to assess the images collected by the robots. However, this work is not without challenges. The images collected were not of easily-identifiable objects, explains Rahnemoonfar, so it took more time to develop algorithms that could distinguish a damaged building from a road that was washed out, for example.

By applying AI and machine learning techniques to the data collected, Rahnemoonfar explains that it allows people to thoroughly assess damage and issues that need to be addressed such as flooding, destroyed buildings, or to detect debris.

Research with community impact

Over time, Rahnemoonfar worked with collaborators to develop the first high-level data, called FloodNet. As a publicly available data set, it drew the attention of people around the world who were interested in using FloodNet in their cities and towns.

Officials in Germany connected with Rahnemoonfar because they were interested in utilizing the FloodNet dataset to train their algorithms to recognize natural disasters throughout the country. “For any future natural disaster, you need similar data sets to train your algorithms,” she explains. “This is the importance of the data set that we prepared.”

“For me, it’s important to know that the research I do has value and impacts the communities after natural disasters,” Rahnemoonfar says, noting that she is eager to continue to analyze large data sets so that the data available more widely.

The next generation of experts

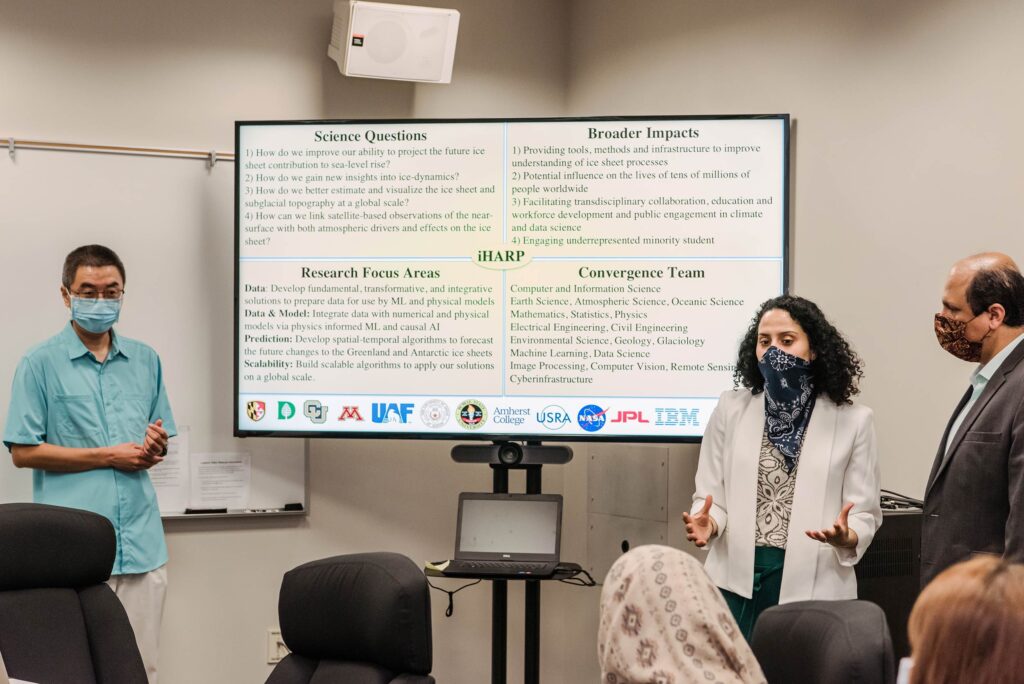

Rahnemoonfar’s commitment to helping communities recently expanded when she received a significant grant from the National Science Foundation, which allows her to make a bigger impact around the world. In September 2021, NSF announced the launch of the NSF HDR Institute for Harnessing Data and Model Revolution in the Polar Regions (iHARP), which Rahnemoonfar is leading as the principal investigator. She and her collaborators will use similar tools from creating FloodNet like data science, machine learning, and AI to analyze enormous volumes of climate data, along with Arctic and Antarctic observations, in ways that could help populations prepare for and respond to climate change risks.

Climate scientists rely on data that are incredibly challenging to disentangle, she explains, and AI offers solutions to analyzing these large datasets. “It is so exciting to be selected as one of the five HDR institutes in the nation, however, this comes with huge responsibility,” she says. “We are the first data science and machine learning institute in the world that is dedicated to research in polar regions.”

The researchers involved with this grant will reduce uncertainties in projecting sea level rise by combining physics modeling, machine learning techniques, and data analysis. The results of their work will inform policymaking to address national and global priorities related to the climate crisis, explains Rahnemoonfar.

The solutions that are developed through the iHARP work will have applications beyond environmental issues. Rahnemoonfar anticipates the team’s research will impact the future of medicine, autonomous driving, and remote sensing, and that the students working on the project will become the next generation of experts addressing these global issues.

*****

All photos by Marlayna Demond ’11.

Tags: COEIT, Fall 2021, Information Systems