As a journalist and an author, UMBC English professor Christopher Corbett has a knack for finding marvelous and mislaid stories past and present.

Christopher Corbett once chased news for the Central Maine Morning Sentinel, the last daily newspaper in New England to use hot type before computers took the noise out of the business.

It was the final gasp of an epoch, when copy was still lowered down to the composing room in a wire basket to a few old goats who remembered the days of the newsroom telegrapher. “We wrote about bean suppers and lists of new books at the library,” marvels Corbett, a professor of the practice in UMBC’s English department and a connoisseur of the everyday marvel. “Everything was news in Maine.”

It was the final gasp of an epoch, when copy was still lowered down to the composing room in a wire basket to a few old goats who remembered the days of the newsroom telegrapher. “We wrote about bean suppers and lists of new books at the library,” marvels Corbett, a professor of the practice in UMBC’s English department and a connoisseur of the everyday marvel. “Everything was news in Maine.”

Corbett was in his early 20s, a newly-minted penny out of Northwestern University, tossed into the world of Watergate journalism after a stint on the Maine Weekly and a spell in Ireland among his ancestral fabulists.

While the young Turks with reporter’s notebooks in Washington were bringing down hog-jowled presidents, Sentinel readers were bringing dead animals into the Waterville newsroom.

“We had a full-time fish and game columnist,” says Corbett, doing what he does best – spinning yarn – over a plate of lasagna in Little Italy. “They’d come in with turtles as big as manhole covers.”

Stories ripe and hanging low for the picking: Hustlers teaching white water canoeing through the mail! Turtles as big as manhole covers!

And therein is the skeleton key to Corbett’s success: the instinct to know that before you can write a good story, you must be able to tell one. And before you can spin the yarns that he has spun as a reporter – along with books such as Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express – it helps to have lived a few.

Some were tragic – “bad things, terrible things,” he says of his early days on the cops and robbers beat. And others were just breakfast, like his Washington Post assignment to cover the first annual Spam Festival in Austin, Minn.

And sometimes, an especially rascally reporter helps herd a story into print and becomes a part of local lore in the doing, as Corbett did in Farmington, Maine – his first outpost at the Morning Sentinel.

“In my four years in Farmington, I never stopped hearing about the Corbett legend,” says Neil Genzlinger, now a copy editor with The New York Times. “Farmington was the kind of backwater where weird news tends to occur.”

The Farmington “bureau” was a room at the back of Mickey’s Variety Store, recalls Corbett, and it was there that an obscure inventor named Chester Greenwood – who invented the earmuff in the town in 1873 – went from local trivia item to famous native son.

“Corbett’s greatest coup,” Genzlinger says, “was when he and Mickey Maguire – an aged local legend – cooked up the idea that the town should celebrate Greenwood. There would be a Chester Greenwood Day and a local state legislator helped draft and pass a statewide proclamation.”

The first celebration took place in 1977. The national media descended on Farmington to cover it. A parade to celebrate Chester Greenwood (a machinist who also patented a steel tooth rake) has been celebrated each December ever since.

“There was a Chester Greenwood and he did invent the earmuff,” twinkles Corbett. “But I helped him out.”

Anative of the Pine Tree State, Chris Corbett has lived in Baltimore since 1980. He has taught in the English Department of UMBC for the past 20 years. The acting chair of the department in 2006 and 2007, he became a professor of the practice in 2006.

Corbett’s “practice” is the written word. Little else in American life – aside from joining the circus or running away to sea, neither of which are what they used to be – allowed for obtaining such experience as being a rookie reporter at the now-quaint institution known as a daily newspaper.

Many of Corbett’s adventures as a newspaperman in Maine became the source of his first book, the 1986 novel, Vacationland.

“I was riding around in a 1967 Buick LeSabre with a 20-channel Bearcat police scanner on the dashboard, covering news and taking pictures in the town where the earmuff was invented,” remembers Corbett. “I was 22 or 23-years-old taking pictures of car accidents. When you’ve seen someone go through the windshield, you tend to remember it.”

A repast with Corbett, whether a plate of pasta on South High Street or coffee at the Evergreen Café near his home in Roland Park, might persuade one that he’s never forgotten anything, except perhaps to clean out the garage like his wife asked him to do.

“I can see it all when Chris talks. It’s a monologue you can’t interrupt,” says Greg Otto, a Baltimore artist known for his local streetscapes – a territory he regularly walks with Corbett. “When he talks of the Old West, a real love of his, I can see those scattered Pony Express stations.”

“Chris Corbett would never want to write a story that’s been written the same way a hundred times,” says Ann LoLordo, a former Baltimore Sun editorial writer and a poet. “His intellectual curiosity complements his curiosity about the common man. What he finds isn’t always pretty, but it makes for good storytelling.”

Not that the public necessarily wants pretty. “No one cares if you went to Bermuda and had a good time,” says Corbett, a veteran of the travel narrative. “Bad experiences make for good stories. People want a nightmare.”

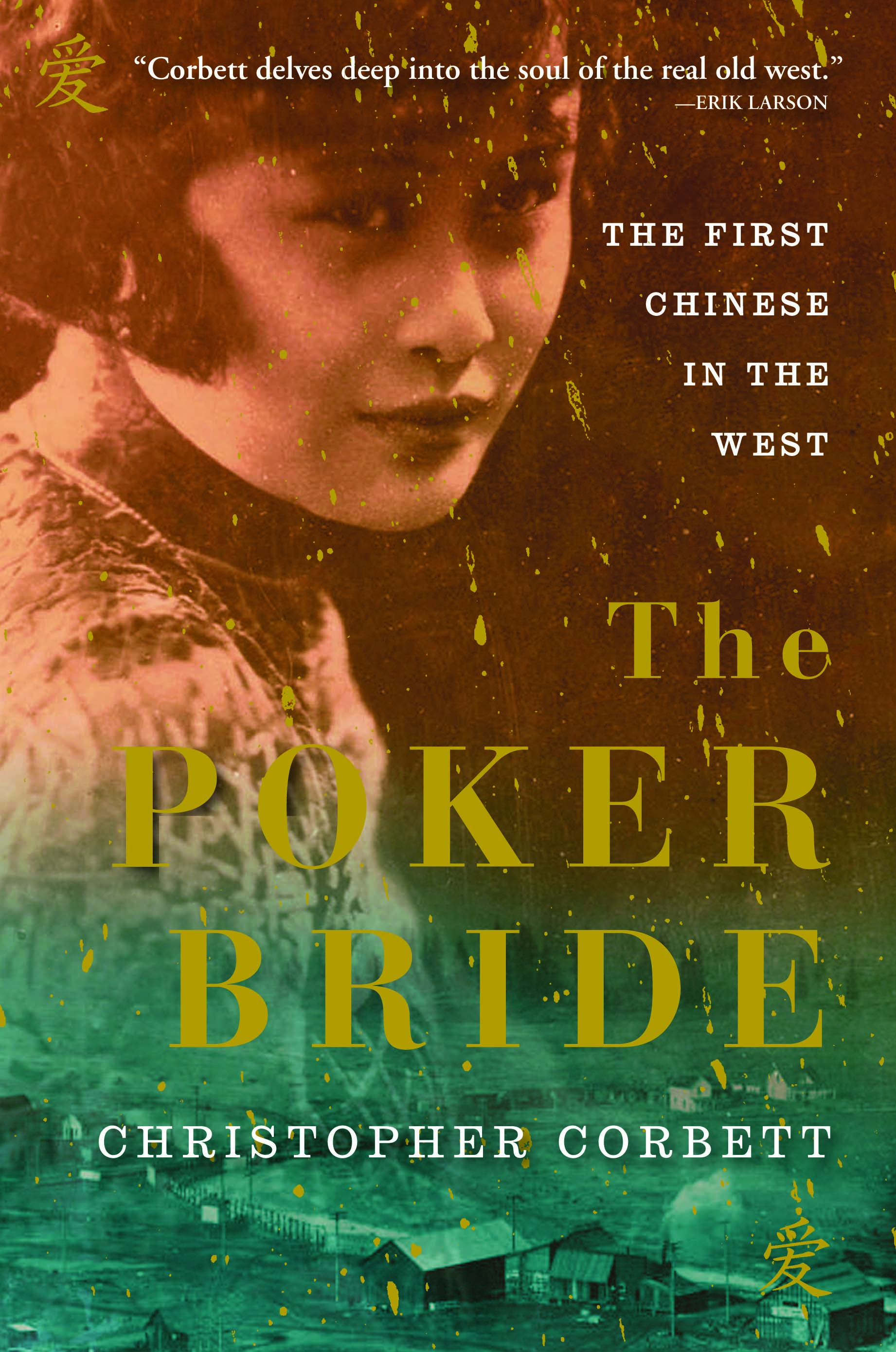

All of Corbett’s skill, considerable charm and skeptic’s love of the Old West are on display in his new book, The Poker Bride: The First Chinese in the Wild West (Atlantic Monthly Press).

The tale, described by Corbett as a “popular narrative,” recounts the legacy of the mid-19th century California Gold Rush, one of mankind’s great migrations. The story is told through the largely dreary and often tragic experiences of Chinese laborers who landed in California to get their piece of the action once the cry of “Eureka!” circled the globe in 1848.

“The welcome wagon was not there to meet them,” says Corbett of the 130,000 or so Chinese – most from the Pearl River delta – who came to the American West through the port of San Francisco. “It was not a particularly jolly episode in American history.”

One of those who landed on the shores of what the Chinese called “the Golden Mountain,” was an illiterate sex slave, a woman who became the winning jackpot of the book’s title, a singular character we only know as Polly Bemis.

Not only was Polly an unlikely survivor whose affable ghost drives the story, but her tale, says Corbett, “put a face on an experience we don’t know a lot about. “The Library of Congress has lamented the lack of primary source material for the Chinese in the American West… Their story has been told from the perspective of this country, and all references to them are either comic or unflattering.”

Edged out of the prime mining claims, the Chinese who arrived in America did domestic work that no one else in the bachelor society of the Old West was willing to do, including laundry and cooking.

“There isn’t a flyblown town from Grangeville, Idaho down to Nevada that doesn’t have a Chinese restaurant” that harkens back to the Old West, said Corbett. “The more I poked around, the more Chinese I found.”

As the decades wore on after the California Gold Rush, fewer Chinese were admitted into the United States. Legislation was passed in 1882 prohibiting their entry for a decade, a law that was then renewed.

The racist phrase “a Chinaman’s chance” – an epithet applied to the fate of a Chinese immigrant whether in a court of law or an argument over a pig – represents the odds the entire group had in a white man’s world.

Says Corbett: “The Chinaman’s chance is no chance at all.”

Polly Bemis survived an era of fatal fights over sex slaves imported from China (with the Chinese favoring hatchets over six-shooters) that appeared in newspapers as late as World War I.

Corbett claims she outlived the hate that labeled her and her brethren a “yellow peril.”

Polly beat the odds.

If Corbett’s instincts for the tales told in The Poker Bride and Orphans Preferred (released this year in paperback to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Pony Express) were nurtured at the Morning Sentinel, they were honed in his seven years as a reporter and editor for the Associated Press (AP).

At the storied wire service, he says, “You were taught to be careful, to ask questions.”

Corbett first shoveled AP copy in Hartford, Conn., the one-time home of Mark Twain, that rare American writer, he points out, who wrote passionate defenses of the immigrant Chinese in the Old West, particularly in the 1872 classic, Roughing It.

From Hartford, Corbett landed in Baltimore when his wife, the Pulitzer Prize-winning editor Rebecca Corbett (now with The New York Times), took a job with the Sun.

If “everything” was news in Maine, the characters behind bizarre tales along the Patapsco knocked on a reporter’s door to introduce themselves in Crabtown.

“Baltimore is ground zero for man-bites-dog stories,” he says. “More men bite dogs here than anywhere on the Eastern seaboard. I have interviewed many a lady who’d taught her parrot how to sing ‘Home on the Range.’”

Reporting for a wire service, Corbett said, was “like being a short order cook in a mental hospital. You learn to work quickly because all of the patients wanted something different and they wanted it right now!”

It was a life, he said, about as far removed from the mood of a college campus as the plates of noodles shared among Chinese mule packers during the California Gold Rush were from the salons that nurtured Edith Wharton’s society intrigues.

The life of kings, to quote H.L. Mencken, if the monarchs happened to reign over people who talked funny, dressed funny and had absolutely no idea how funny they were. “My first AP office was at 210 North Calvert Street,” he recalls. ‘The other tenant was some operation that dealt with junkies. The mounted police used to tie their horses up at the back door.”

Now something of a vanished world, it bore “no resemblance to the world of UMBC. I might as well have come off a spaceship,” says Corbett, under whose mentorship The Retriever Weekly student newspaper won national awards in 1995 and 1996.

Trying to get a young writer’s radar to pick up the presence of other worldly characters who crowd the shores of the Chesapeake is somewhat more difficult than teaching the five Ws of news gathering, says Corbett.

“I tell my students to find a good story and then let the story carry them,” he says. “I use the annual ‘Night of 100 Elvises’ as an example. How can you not get a base hit out of 100 fat guys who think they look like Elvis?”

Though no one can recall Elvis stopping by the Baltimore AP office in the years that Corbett was there (1980-1984), a frequent source of news was the late John Kafka, founding legend of “Polock Johnny’s” polish sausage, once promoted as the “un-burger.”

Kafka was an ironclad original who made his bones and a boatload of shekels around the corner from the AP office on “The Block” before a heart attack took him in 1986. “Here is a big difference between now and then,” says Corbett. “Polock Johnny would not stop at UMBC to discuss metaphysics with us. I suppose it was all a long, long time ago.” But not quite as long ago was the day the woman who would be known as Polly Bemis landed on the crowded wharves of San Francisco in 1872 to work the sex trade, having been sold for bags of seed in China by her impoverished parents and resold in California for $2,500.

Polly was later won in a poker game by a borderline cad and deadbeat gambler named Charlie Bemis who – in a move that kept her in a New World that so many of her countrymen abandoned in time – made her his wife.

It is Polly, a true pioneer of the Idaho Territory who died in 1933 at the age of 80, who shadows The Poker Bride as the California Gold Rush and its aftermath drive the story.

“We do not have anyone else like Polly – period. Hers is as much of a story as we have that is also true about someone who survived the Chinese sex slave trade,” says Corbett. While kicking around the Western United States on another story, Corbett kept coming across deep veins of memories and remnants about the first Chinese communities there. And he was intrigued to discover that while “the whole world is buried” in Old West cemeteries, there was scant trace of any Chinese interred there.

Bone collectors had come from China to take the corpses home.

But not Polly.

She is buried near the home that friends built for her along the Salmon River, her cabin a museum on the National Register of Historic Places.

“Polly shines a light on a sad and little-explored experience about the way the Chinese were treated in the West,” says Corbett. “In the end, it was all a melancholy tale.”

Tags: Summer 2010