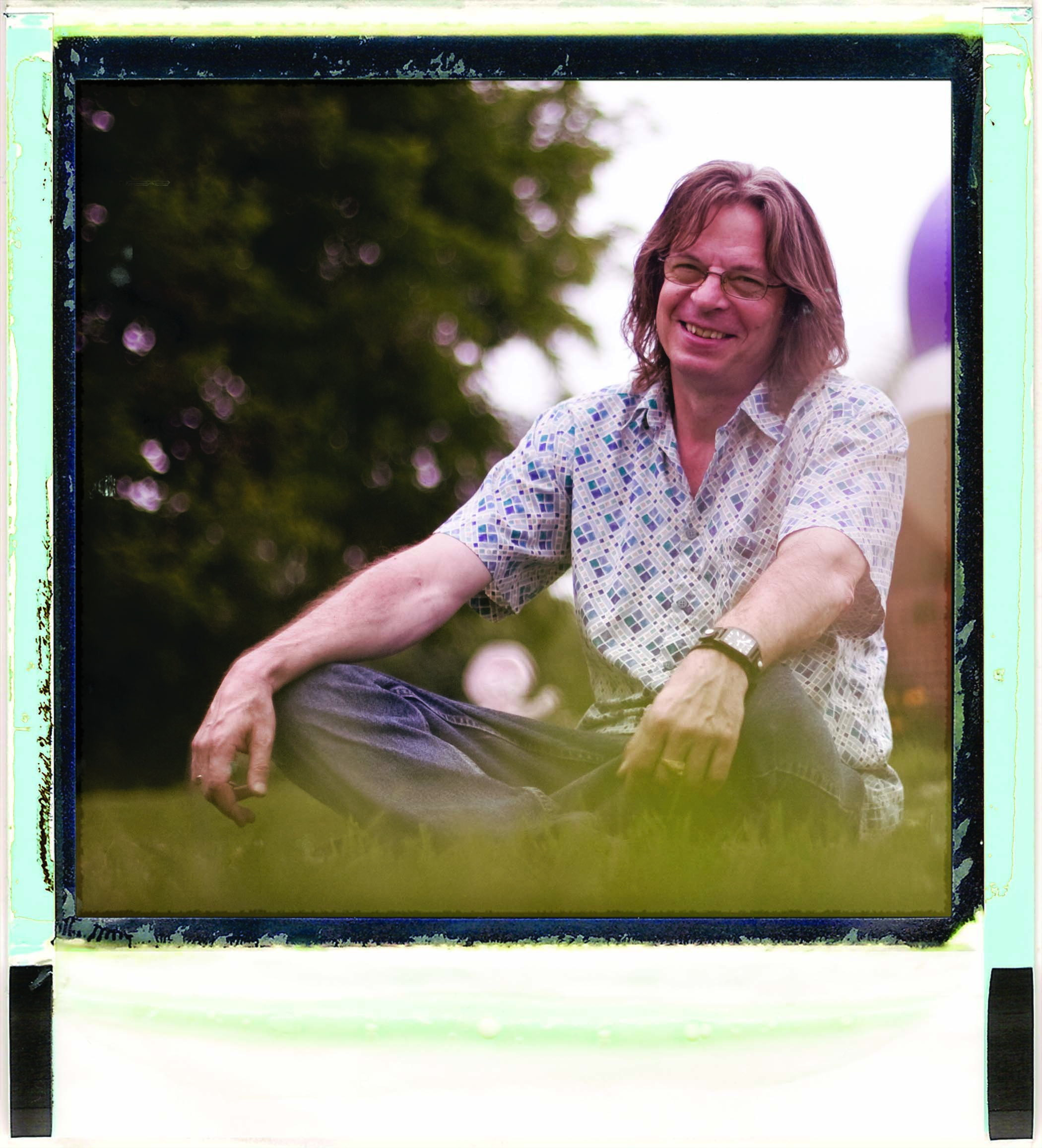

You might know John Strausbaugh ’74, interdisciplinary studies, from the books that he’s written on odd and controversial topics – including Elvis culture (E: Reflections on the Birth of the Elvis Faith), boomer rock (Rock ‘Til You Drop: The Decline From Rebellion to Nostalgia), blackface (Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult & Imitation in American Popular Culture) and the sissification of America (Sissy Nation: How America Became a Culture of Wimps & Stoopits).

But Strausbaugh’s been influential behind the scenes in contemporary journalism as well. As the editor of New York Press in the 1990s and the early part of this decade, Strausbaugh discovered and/or nurtured a wide array of new literary and journalistic talent including Oscar-winning screenwriter William Monahan, and a host of columnists-turned-authors such as Jim Knipfel (Slackjaw, Quitting the Nairobi Trio), Jonathan Ames (What’s Not to Love?: The Adventures of a Mildly Perverted Young Writer), Norah Vincent (Self-Made Man, Voluntary Madness) and Amy Sohn (Run Catch Kiss).

Strausbaugh is also well-known for an occasional column (and web-video feature) that he writes for the New York Times called “Weekend Explorer.” In each column, he investigates the disappearing legacies and odd tales of various New York City neighborhoods. So UMBC Magazine asked Strausbaugh to do something similar – and more far-reaching – with his own hometown. Here’s what he found….

My twin brother, Richard, and I were born in Baltimore on Halloween, 1951. He was the treat, I was the trick. I went to Loyola High School and UMBC, and lived in and around Baltimore until 1990, when I moved to New York City, where I’ve been since. When I come back to visit, I’m always struck by what’s changed in my absence – some new things I like, some I hate. And I go looking for familiar haunts, remnants of the Baltimore I knew. Old Bawlmer.

Hampden is one of the Baltimore neighborhoods that feels the most changed since I moved away. In my day it was not hip, cute, gentrified or ironically self-aware. You might well have been addressed as “hon” there, or anywhere else in the city, but never in a place called Cafe Hon. Hampden was a bastion of white, working-class Baltimore, mostly urbanized country folk. They spoke some of the purest deep-dish Bawlmerese you ever heard. Outsiders needed a native interpreter. I remember watching a parade on W. 36th Street – maybe it was Fourth of July, 1976 – standing behind a young Hampden dad with his son on his shoulders. The kid pointed to a patriotic balloon going by.

“Wazzat dad?”

“Atza blune, son. See whatzawnit? Atza iggle.”

Hampden was where Santy come dayna chimbley and also, I believe, where I was first stumped by the verb “obble.” As in, “Ah dayn knayow what the problum is, but Ahm gonna obble it and fahnd ayut.”

Frazier’s, the W. 36th Street bar and restaurant, seems to me to do a pretty good job of balancing Old and New Hampden. (The current location is the “new” Frazier’s; the old one, several blocks away and harder to find, was very Old Hampden.) Maybe it works only because Old Hampden tends to have its elbows on the bar in one room, while New Hampden is shooting pool in the larger, loungey other room. Anyway, everybody seems to coexist in peace. It’s not chic, and the waitstaff don’t work too hard at charm-citying you, hon. It’s just a bar where you go for cheap drinks and platters of respectable food.

Besides my friends and family, what I miss most about Baltimore is the crabs. It’s axiomatic that you can’t get steamed crabs in New York or a crabcake worthy of the name. They’re all cake, no crab. And forget about such delicacies as scrapple, pit beef or Taylor Pork Roll.

For steamed crabs, my sister Jane takes me to L. P. Steamers, an old-school, family-run crabhouse on Fort Avenue in Locust Point. Afterward, to wash down the Old Bay, we drive a few blocks farther east to J. Patrick’s Pub on Andre Street, one of the last of the traditional Irish music spots that in my day included Kavanaugh’s and the Gandy Dancer. At J. Patrick’s they pull one of the best pints of Guinness I’ve tasted in the U.S. – neither warm nor chilled but basement-cool, with a creamy head.

Unlike Hampden, Fells Point, Canton or the Inner Harbor, Locust Point looks and feels mostly unchanged to me. Narrow streets lined with small rowhouses run down the gentle slope from Fort Avenue to the waterfront and the Domino sign. Young mothers sit out on their stoops on a summer evening, smoking and gabbing quietly as their kids splash in tiny plastic wading pools on the meticulously swept sidewalks. The buildings are low and the sky is wide and you can watch the weather sweeping over the city from the west and not hear or acknowledge the hubbub over in Camden Yards and Harborplace.

When I was growing up, Bawlmer kids’ three favorite places on earth were Ocean City, Gwynn Oak Amusement Park and Enchanted Forest. (Well, Gwynn Oak was a favorite for white Bawlmer kids: It was segregated, until the early ’60s, as were swimming pools and other recreational places. Old Bawlmer had its nasty side, too.)

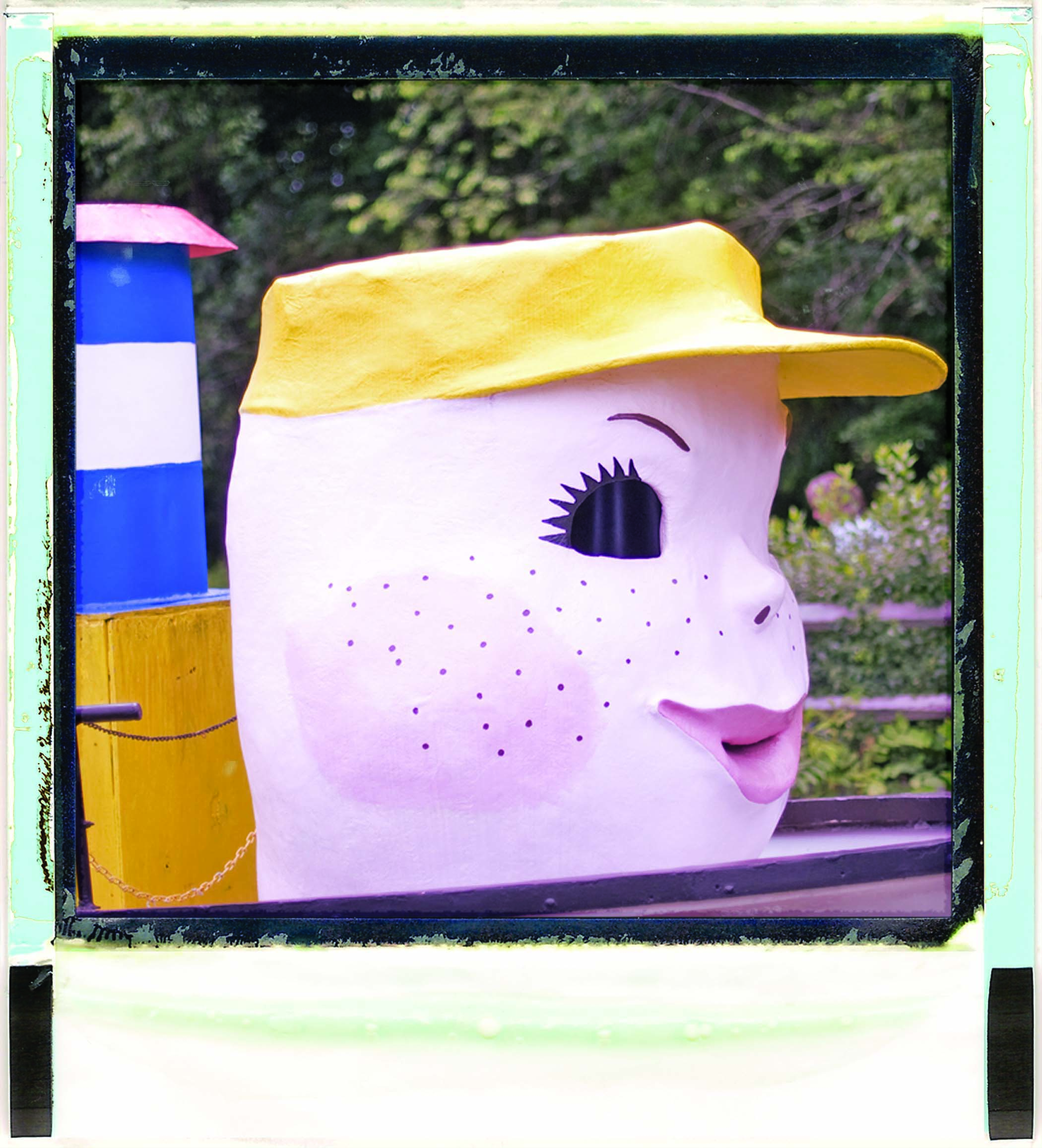

The Ocean City I knew was obliterated by the current metropolis-by-the-sea decades ago. Gwynn Oak closed in the early ’70s. Enchanted Forest, on Route 40 near Ellicott City, lasted into the late ’80s. It was fairytale-themed and magical in a low-rent way.

For a couple of years in the ’70s I rented a woodframe shack on Frederick Road just west of Ellicott City with my friend James Taylor. (Not the folksinger, but the co-founder of the American Dime Museum, another great, lamented Baltimore institution.) We were told the house was built as slave quarters and that it was haunted. We believed both. It was certainly haunted by bees, a giant hive inside one whole wall. If you put your ear to it you could hear them in there humming like fluorescent lights.

Our neighbors to one side were a poor white family, to the other a poor black one. The white family didn’t like us and rarely spoke. Their hound used to stand in the little stream that trickled just behind the houses and bay at the moon all night. The black family was more friendly. The dad used to call both me and James “Cap’n,” as in, “Nice morning, eh Cap’n?” Cows and horses wandered the big green hill across the road. Mornings they’d drift down to the fence and blink at traffic racing by.

Enchanted Forest was still open, and we’d go over there once in a while. It wasn’t doing much business in those days and looking pretty forlorn. I fantasized about buying it and turning it into a private compound for me and my friends. I’d take the Three Little Pigs’ House and put apartments in the Old Lady’s Shoe.

What did happen, inevitably, was the Enchanted Forest Shopping Center, incorporating the park’s Old King Cole sign and its storybook castle entrance, but letting the rest of the site sadly deteriorate. Starting in 2004, the Clark family, whose Clark’s Elioak Farm is on Route 108 between Ellicott City and Columbia, cut a deal with the shopping center to move a lot of Enchanted Forest there. They and volunteers (including Mark Cline, sculptor of the wonderful Foamhenge down near Natural Bridge, Va.) have beautifully restored and re-created the institution. They’ve got the Shoe, and Cinderella’s pumpkin coach, and the Three Bears’ House, and Li’l Toot the Tugboat, and the Easter Bunny’s Easter Egg house, and a bunch more, all spread out nicely on the farm’s fields and through its woods. When I was there this summer there were lots of families, of course, but also some unaccompanied adults like me, wallowing in guilt-free, unself-conscious nostalgia.

Baltimore was always an Elvis town. Old-timers will remember Miss Bonnie’s Elvis bar on Fleet Street. It closed after Miss Bonnie died in the early ’90s. Around the same time, my friend Carole Carroll started the annual Night of 100 Elvises, which will happen for the 16th year this Dec. 4-5. As a big fan of the King, I’ve been honored to come down and help emcee the event a few times. I’ve been to Elvis tributes in Memphis and elsewhere, but the Night is sui generis, featuring dozens of Elvis tribute artists (not “impersonators,” thank you) of all ages, sizes and skills, from little kid Elvii to kung fu Elvii to the fabulously matronly all-Canadian-ladies revue, the Graceliners.

Working the stage at an Elvii event is a treat. True Elvii are the King’s ministers here on earth, and they take Elvis’ code of behavior seriously. I’ve never been around more polite entertainers. Meanwhile, the crowd that stuffs the hulking old Lithuanian Hall in the ghetto of Sowebo is always an interesting mix of the real Elvis faithful and curious hipsters. On the Sunday after, Carole and some of the Elvii participate in the Hampden Christmas parade, another excellent Baltimore tradition, even if the weather always seems to be viciously cold. Carole and the Elvii ride in beautiful vintage cars provided by the Karb Kings club (klub?). It’s a hoot.

For a relatively small city, Baltimore is rich in museums. I’ve been to a lot of museums around this country and a few others, and two of my favorite are in Baltimore: the Walters, which I’d say is a world-class museum of its type, and the American Visionary Art Museum, which I believe is pretty nearly unique. Being an entire museum devoted to art by visionaries, outsiders, loners, the untrained and the institutionalized, it makes great sense that it’s in Baltimore, too.

The big group show that opens at AVAM in October of this year, “The Marriage of Art, Science & Philosophy,” curated by the outsider art expert Roger Manley, will include work by an amazing artist I met earlier this year in Raleigh, N.C., Renaldo Kuhler. Over decades, Renaldo created a private fantasy world, Rocaterrania, which he conceived in stupendous detail – the people, their political history, their language and alphabet, architecture, clothing, cinema, music. When I met him, it was clear that Renaldo, a man as funny and courteous as he is eccentric, lives with one foot in this world and the other in that one. Brett Ingram, a North Carolina filmmaker, made a fascinating documentary about him, Rocaterrania.

This summer Jane took me to a bit of Old Bawlmer that was new to me: North Point State Park, out at the tip of Sparrows Point. It’s a mix of beach, farmland and untrammeled marshland, on a peninsula jutting into the Chesapeake. In September 1814, British invaders slogged through it and many perished of the heat and humidity. A hundred years ago it was an amusement park that folks from the city reached by streetcar. The old trolley pavilion has been restored.

There’s also a long, narrow pier from that era, poking well out into the water, where shirtless, tattooed fishermen dropped their lines against a sweeping vista of the bay, the low blue smudge of the Kent County shoreline across the way, the bluish tracery of the Bay Bridge in the distance.

Beside the pier is a small crescent of beach, not fancy, where white, black and hispanic families, whom I judged to be mostly working-class, lay around or stood laughing up to their hips in the bathtub-warm bay. Back from the beach are tree-shaded picnic groves where charcoal smoke rose from grills and dragonflies bobbed in breezes that tasted of hot dogs and hamburgers. In one grove a group of Russian men in Speedos kicked around a soccer ball.

Behind the beach there are trails through back-bay woodlands and out along the fringes of wide, wet marshlands where egrets crank their long wings and muskrats build “sheds,” like down-market beaver lodges. Except for an occasional jet high overhead it got very quiet out there, just the sound of breezes sifting the heads of the marsh grasses. I’d never been there in my life, but it made me pine fiercely for Chester Peake and The Land of Pleasant Living and the lazily, languidly beguiling city where I grew up.

Tags: Fall 2009