When UMBC Magazine put a call out for questions about our institution’s history and mysteries, alumni from across our 50+ years of graduating classes responded. Accessing our campus experts, we compiled and addressed the top nine questions below.

What’s the origin of True Grit? Are there really secret campus tunnels? Why don’t we have a UMBC football team? Why is there a silo at the west entrance to campus? Who made the decision about the shape of the loop? Why was the historic Hillcrest Building removed? When did UMBC get its first computer? Who are some of the top performers who’ve played on campus? What was UMBC’s founding class like? What questions do YOU have?

The Hillcrest Building

“Why was the Hillcrest Building torn down? What was the history behind this structure?

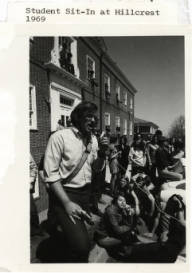

What remains of the Hillcrest Building today is a conspicuously vacant stretch of grass nestled among UMBC’s West Hill and Terrace Apartments. Yet Hillcrest occupies a very important place not only within UMBC’s history, but also in the history of mental health treatment in the United States.

Hillcrest served as the site of the university’s first administration building in 1966. It hosted a variety of university functions, including the housing of student organizations and the operation of the popular basement social club known as The Rattskeller (or “Ratt”) for 34 additional years until its closure in 2000. The building also inspired a great deal of curiosity in the time between its phasing out of campus use and its eventual demolition in 2007.

As curious as many students and faculty and staff may be about Hillcrest as a significant campus site, the building’s history before it was acquired by the University System of Maryland is perhaps even more significant, intriguing, and problematic—and also a probable source of campus fascination with the building.

Hillcrest was the first structure in the history of the United States to be designed and erected specifically for the containment and rehabilitation of “criminally insane” patients. It opened in March 1922 as an extension of Spring Grove State Hospital, and remained in operation until its closure in 1965.

Indeed, the Hillcrest Building’s roots as a locus of pioneering psychiatric care and as the cradle of the planning and early administration of UMBC represent two contrasting historical identities that, when recalled simultaneously, ultimately made preserving the building (and it baggage) an impractical task.

The first facility dedicated to the treatment of the criminally insane in America was founded in 1859 at the Auburn State Penitentiary in Auburn, New York. Similar facilities appeared across the country in the years that followed, and all of them were created as subsidiary components of their respective state penitentiaries rather than as independent medical institutions poised to handle the unique challenges of treating individuals who were then-labeled as “criminally insane.”

J. Percy Wade, the superintendent of Spring Grove State Hospital from 1896 – 1927, pursued the creation of a special building for the criminally insane in 1917, after noticing the inadequate treatment options available, especially for shell-shocked soldiers returning from World War I. Wade sought to both alleviate the burden placed on state penal institutions that were ill-equipped to deal with such patients, and renew the role of the hospital environment as a place of refuge.

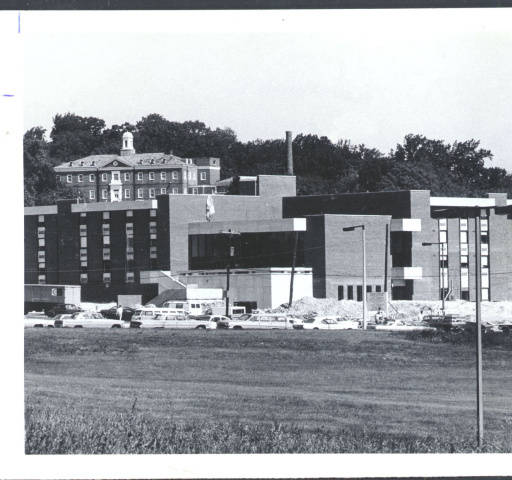

In 1921, the Maryland legislature voted $135,500 in funds to construct Hillcrest. The building stood approximately 40 feet by 120 feet (23,349 sq. ft.), and its brick and sandstone exterior emulated Georgian architectural motifs. Hillcrest was located approximately one mile from the main Spring Grove campus, in an area surrounded mostly by farmland and steep topography. Its location was chosen in an effort to hinder escape attempts (and to ease in the recapturing process should an escape be successful) and to maximize community security while minimizing disruption to the main campus. The quiet surroundings also were thought to be therapeutic to patients.

Unlike patients on the main hospital campus, Hillcrest patients were not allowed to watch motion pictures, dances, or theatrical shows for fear of inciting violence or escape attempts. The prospect of escape was particularly feared by hospital administrators because of the safety risk for patients and potential embarrassment to the hospital.

These fears, along with advances in psychiatric techniques, led to the construction of isolation rooms in 1927 for unruly patients. The carefully selected patients admitted to Hillcrest also engaged in occupational rehabilitation, often sewing their own clothes, growing crops, and tilling the surrounding farmland.

By the mid-1950s, Hillcrest not only faced overcrowding, but also it had declined as the leading facility for the care of criminally insane patients in Maryland after the opening of the new Clifton T. Perkins Hospital in Jessup. Interest by Spring Grove administrators in selling the property coincided with the University System of Maryland’s choice of site to create UMBC, and Hillcrest was part of the 435-acre tract upon which the university was founded.

Hillcrest’s key role as the university’s first administration building, Residential Life headquarters, and hub for campus Greek organization and social life faded as UMBC developed newer and more functional spaces, including University Center and The Commons. But even after its closure in 2000, Hillcrest retained an outsized place in campus folklore and legend.

Campus tales about the building drew upon from Hillcrest’s psychiatric roots, positing that a patient who served as a model for the character of Hannibal Lector in the novel (and the film) The Silence of the Lambs was once treated within its walls. Others reported seeing ghostly figures in windows or hearing strange sounds emanating from inside. And, of course, Hillcrest’s actual history as a former institution for the most violent and volatile mental health patients of its time certainly stood in stark contrast to its aspirations as an honors university.

In its final years, Hillcrest stood out distinctly from the neo-contemporary architecture of of the rest of the university. Yet the building’s lack of “unique” exterior architectural features (considering the era of its construction) also meant that it had difficulty being placed on state and national historic registers. Local preservationists came to the building’s defense when UMBC announced plans in 2004 to raze Hillcrest to create additional parking and living space on campus. One group—a newly-formed Hillcrest Historical Society—successfully lobbied the Baltimore County Historical Trust to survey the building and resulted in its placement on the trust’s preservation watch list.

Despite the publicized involvement of community watchdog groups, UMBC eventually obtained clearance to demolish Hillcrest in 2006 and did so in July 2007. Yet Hillcrest and its elusive past have not been forgotten, and the building represents a bygone era that remains impressive both for its contributions to medical history and the foundation of the university itself.

– Trevor J. Blank ’05

The Silo

“The silo on UMBC Boulevard suggests a connection between the university and farming. What was that property before it became UMBC?

Former Maryland Comptroller Louis Goldstein’s brainstorm to found the university on land owned by Spring Grove Hospital between Catonsville and Arbutus placed the campus on farmland once worked by students at the Baltimore Manual Labor School—an institution that used agricultural labor as a means to improve and reform impoverished boys.

So why wasn’t the silo demolished when construction on UMBC began in the 1960s? One theory was that the old structure was kept as a remembrance of the site’s history as a farm. Founding chancellor Albin O. Kuhn addressed this very question in 2006, suggesting a more practical reason at the bottom of the question: The silo was too large and heavy to move or demolish. Kuhn reasoned that the old silo “wouldn’t bother anybody.”

The Tunnels

“Does UMBC have secret underground tunnels? Why?

Mention the word “tunnels” to many UMBC alums, and you’re bound to get a story.

Often it’s a second- or third-hand tale. A friend of a friend, who may (or may not) have actually been there. Very often, shenanigans will be involved in the story. There are even conspiracy theories.

Yes, the tunnels do exist. Actually, they are quite extensive. It is a 6,000 foot long system of utility passageways humming beneath the campus. Yet, very few people have actually entered the tunnels.

“Everybody knows they’re there, but they can’t get in, so it’s very easy for stories to get started,” says Rusty Postlewate, assistant vice president for facilities management, one of the few to hold the key that unlocks this campus mystery.

As envisioned in the original blueprints for the UMBC campus, the service tunnels house what can be described as the central nervous system of the university, with large aluminum tubes encasing all of the main utility lines, including hot and cold water, electrical, phone, and fiber optics, for easy maintenance access by facilities workers.

Running directly beneath Academic Row (also known to Facilities Management staff as “196,” or the height above sea level), the tunnels reach from the Administration Building all the way to the Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery. Offshoots connect The Commons, the Public Policy and Physics Buildings, as well as the Central Plant. As the campus has grown, the UMBC tunnels have expanded along with it, most recently to the new Performing Arts & Humanities Building.

Walking beneath the campus feels a bit like entering another world, with concrete and tubing as far as the eye can see. But touches of UMBC filter through. Near an entrance point in The Commons, a hand-painted tag reads “John ’87.” In another section, a “You Are Here” map puts the twists and turns into perspective.

At a lanky 6 foot 4 inches tall, Postlewate ducks his head to avoid metal tubing hanging from the ceiling of one of the connecting passageways—a reminder of one of the main reasons why most people aren’t allowed down here. With pressurized water of 350 degrees and 13,200 volts of electricity running end to end, it’s just not safe for visitors.

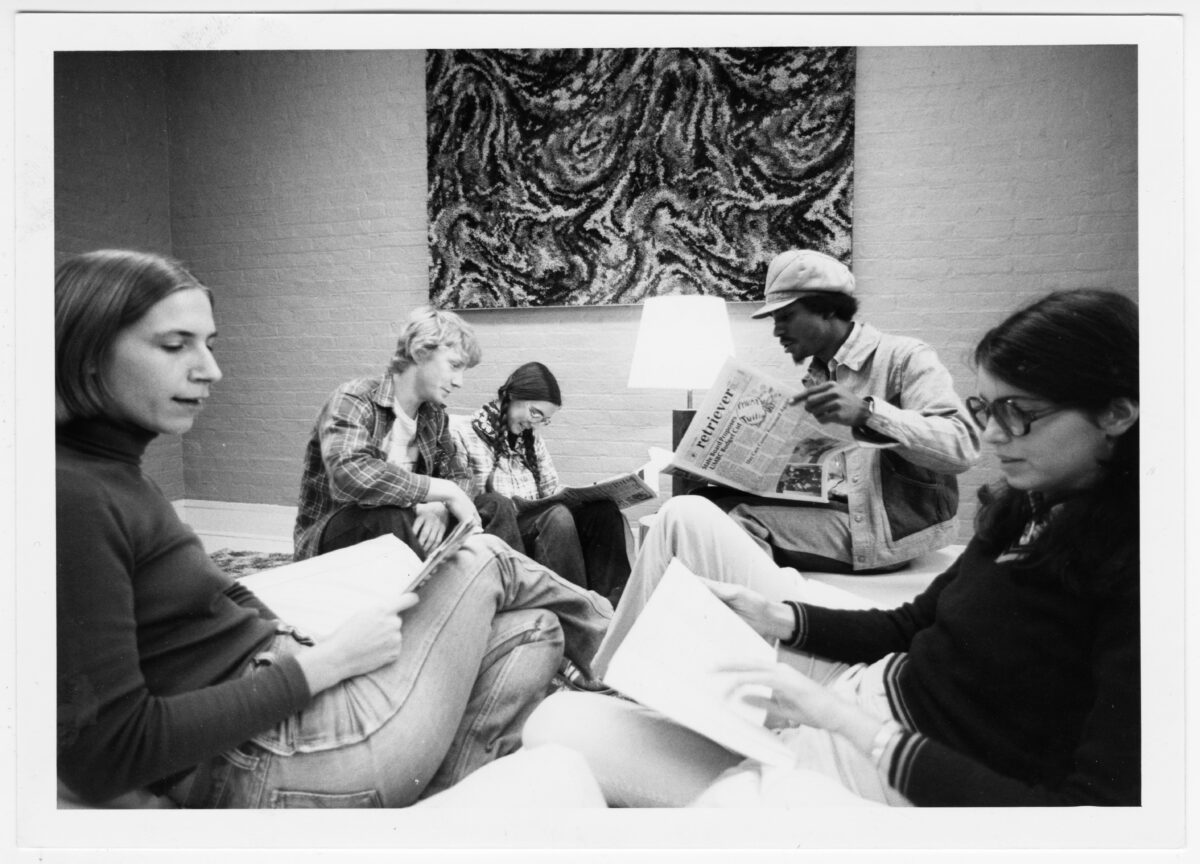

That hasn’t kept generations of alumni from speculating about the tunnels, though. Take a spin through the online archives of The Retriever Weekly, and you’ll find a broad history of student perception of the tunnels—both true and imagined.

An article from the September 25, 1972 issue of the newspaper stated that a “very select group of handicapped students” was allowed to use the tunnel system to travel between buildings located along Academic Row. (This is not currently allowed.) Former UMBC Physical Plant director Guy Chisolm observes that other students were barred from the tunnel area for a rather mundane reason (insurance consideration), but then adds that “we don’t want to give anybody the opportunity to commit any acts of sabotage.”

Why might this have been on Chisolm’s mind in 1972? The interview was conducted a few months after the end of the spring 1972 trial of Catholic anti-war activists (known as the “Harrisburg Seven”) ended with a hung jury that freed the defendants. Among the charges leveled was that the activists wanted to set explosives in steam tunnels under government buildings, and one of the seven defendants was Philip Berrigan, a Catholic priest and the primary organizer of the landmark “Catonsville Nine” action in 1968 where draft files were burned at a Knights of Columbus hall near campus (which also housed the Selective Service).

More often, however, UMBC’s tunnel system has been the object of playful speculation, particularly in several issues of The Retriever Weekly’s annual April Fool’s Day edition. The April 1st issue from 1973 spends the good part of a page mashing up two bits of campus folklore by describing a “Man Discovered in Tunnel” who turns out to be an escapee from the Spring Grove State Mental Hospital. Another parody—in the March 29, 2005, issue of “TEH DECEIVAR” – features the front page headline “Bodies Found In Mysterious Labs Under Hillcrest,” and spins a funny and complicated story involving the police, zombies, and an unidentified man in a tweed jacket.

Otherworldly creatures aside, campus maintenance workers are the primary visitors to the campus tunnels these days. Even UMBC President Freeman A. Hrabowski, III doesn’t have a key, says Postlewate.

Greg Stryker ’97, psychology, recalls his own memories of the tunnels from when he worked as a maintenance assistant for the Office of Residential Life. “We found all sorts of cool stuff on that job. I don’t remember doing anything out of the ordinary… just walking around the tunnels to see where they led,” he said. “Stories were that (the tunnels) were put in so the faculty could escape during a campus riot. [A] funny thought that gained some traction, but they were obviously service tunnels.”

Jay Lagorio ’08, computer science, snuck into the tunnels a few times. And he has the pictures to prove it. “At one point, myself and another student made it our mission to map out everything that was down there and be experts on how the whole university connected together,” he recalls. “We had a variety of ways to get in but the one thing we never found, though not for lack of looking, was an outdoor entrance. The best memory I have was hearing maintenance people walking towards us very, very late at night. We were pretty sure they didn’t know we were there, but I don’t think I’ve ever had to run so quickly or quietly before or since. The next day we heard there had been an electrical problem over the previous night so we didn’t think they were looking for us.”

Several years ago, Postlewate’s crew had to stake out a section of the system near The Commons after food started disappearing in the middle of the night. That free meal ticket didn’t last long, he says with a laugh. “Ah, that’s just students being students.”

– Jenny O’Grady

The Shape of the Loop

“Is it true that you have to run around the Loop Road to get rid of the calories in one donut? I heard this when I was a freshman 20 years ago.

The caloric reduction in running the 2.2 miles of Loop Road (officially known as Hilltop Circle) likely depends on your metabolism. But we do know that the road itself was the result of careful planning by Albin O. Kuhn and the team that designed the university before it opened in September 1966.

Kuhn visited many universities before proposing a design for UMBC. “In essence, UMBC became a compilation of the positives and negatives that Kuhn experienced,” says Nichole Zang, a master’s student in UMBC’s historical studies program who also works in the Special Collections department in the university library named after Kuhn.

Kuhn observed in a 1994 interview that his plan for UMBC aimed to compensate for “the mistakes of a campus like College Park.” He believed the circular design, with most of its academic buildings located in the center, and utility wires buried underground, would keep traffic running smoothly, and allow students to walk to classes rather than drive across a sprawling campus or cross busy roads. The loop would also connect seamlessly to major routes near UMBC, including I-95, the Baltimore Beltway, and Wilkens Avenue.

That vision and the loop road have sustained UMBC through its first 50 years—as well as giving members of the university community and neighboring residents a circle to jog or pedal off those donuts.

– Julia Celtnieks ’13

Why the Chesapeake Bay Retrievers?

“What’s the real story behind True Grit? Why was a Chesapeake Bay retriever chosen as the school’s mascot?

In the fall of 1966, a piece in the inaugural issue of UMBC News (later dubbed The Retriever Weekly) announced a contest to choose a mascot for the brand new university. Entreating readers to choose a mascot “that will become the loveable pet of students for years to come,” the article garnered dozens of entries, ranging from whimsical fancies (unicorn, angel) to prosaic suggestions (muskrat, crab).

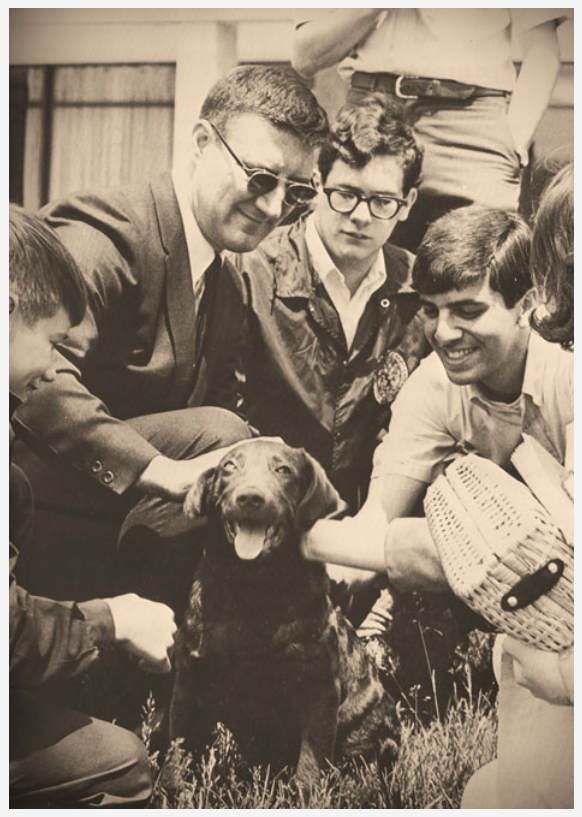

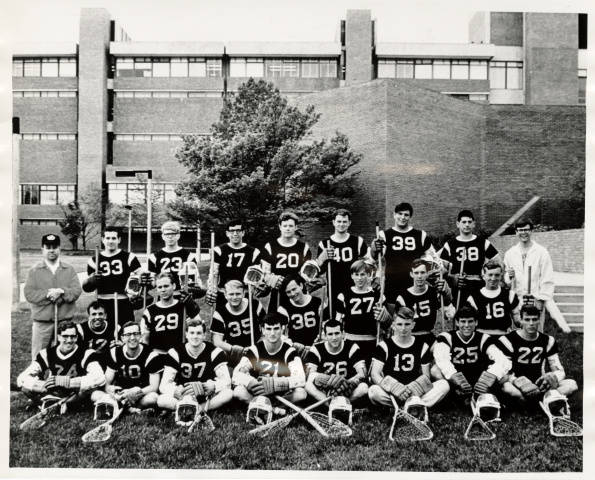

On October 30, 1966, the university announced that student Tom Berlin had won the contest with his nomination of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. And soon after, UMBC received its first live mascot in the form of a spirited Chesapeake Bay Retriever pup with curly brown fur. Dog breeder Claude L. Callegary—whose son attended UMBC and played lacrosse for the Retrievers—donated the dog to the school in the spring of 1967. Another contest failed to yield a name for the puppy, which eventually became known as “Campus Sam.” In the absence of any formal arrangements to care for the dog, Guy Chisolm, UMBC’s first director of physical plant, volunteered to take the retriever to live with his family in their Catonsville home, which was adjacent to the campus.

Richard Chisolm ’82, interdisciplinary studies, who has made a notable career as a documentary filmmaker, recalls that “Sammy” (as he and his siblings Mac and Susie called the puppy that their father brought home) grew into a large dog with a fierce bark who loved to swim in the family’s swimming pool. He and his siblings were responsible for training and walking Sammy. From time to time, coaches or faculty members from UMBC would borrow Sammy for games or campus events, where he would be adorned for the occasion with a black and gold UMBC scarf.

Richard Chisholm adds that Campus Sam’s life, though largely peaceful, was nearly cut short one day when he escaped the family’s fenced yard to chase after a deer. Leash in hand, Richard ran after Sammy and witnessed the determined dog crash headfirst into a moving car. Thankfully, Sammy survived with little more than a permanent bump on his head.

UMBC has had a number of subsequent live Chesapeake Bay Retriever mascots—as well as mascot images to represent the university. (Two of these images, including the most recent, have been created by Jim Lord ’99, design director of UMBC’s Creative Services.)

But perhaps the most prominent symbol of the university is a 500 pound bronze cast sculpture of the mascot, dubbed “True Grit,” which graces the plaza between the Administration Building and the Retriever Athletic Center (RAC).

UMBC commissioned artist and alumna Paulette Raye ’87, who had graduated summa cum laude from the university with a degree in philosophy, to create the sculpture. Raye created the work in a studio at Towson University, using “Nitty Gritty”—a champion Chesapeake Bay Retriever owned by Howard County residents and veterinarians James and Brenda Stewart—as her model.

In an email to UMBC Magazine, Raye recalls that “the mascot was the first dog I had ever sculpted—of any size. It was the only large size sculpture that I had ever done.”

Raye relates that a number of setback delayed the completion of the project. In fact, she writes, the project almost literally melted down.

“The wax casting was made and then sat in the foundry—very warm in there—for a full year before [UMBC President Michael] Hooker released the funds to complete the casting in bronze,” she recalls. “In the meantime, the wax casting had distorted—not terribly, but it did not cast nearly as detailed and beautiful as it had been sculpted because of some warping from the heat that it had sat in for a year.”

Raye also helped UMBC Magazine solve on enduring mystery about UMBC’s mascot that an extensive search for details about the project in the university archives did not reveal: The model’s name was “Nitty Gritty,” so what was the origin of the name “True Grit?”

“‘True Grit’ was the name of the Nitty Gritty’s father,” writes Raye. “Exactly why the mascot received that name, I am not sure, other than it sounded bold and strong—like the team.”

Hooker and UMBC director of athletics Rick Hartzell oversaw an unveiling of the statue—with a tug from model Nitty Gritty himself—at a ceremony on December 7, 1987. In a a letter to Hoke Smith, then president of Towson University, Hooker lauded the statue’s creation at Towson’s art studios as an historic truce in the “traditional Retriever-Tiger” rivalry, and graciously invited Towson’s president to stop by and “see us, and True Grit, when you can.”

True Grit remains a steadfast and enduring campus presence—greeting new students and visitors on their arrival to campus, and bidding a fond farewell to UMBC’s proud new alumni with cap on his head and diploma in his teeth as they graduate. And that shine on his nose? UMBC students have developed a tradition of rubbing True Grit’s nose for luck in their exams.

– Theresa Donnelley ’13 and Richard Byrne ’86

Performances for the History Books

“Who was the most famous performer or group to play a concert at UMBC?

UMBC has had many amazing musical acts play at various venues on campus, including the

now-vanished Gym I, the University Ballroom, the Quad, and the Retriever Activities Center.

But if we had to narrow it down to five performers or groups that have achieved worldwide

fame, cultural influence, and super-sized records (in some cases, all three), and played on our

campus during their respective heydays, here are our answers to this question:

1. Otis Redding: The legendary soul singer, who died so tragically at the height of his fame in

December 1967, played UMBC’s Gym I during the university’s inaugural “Spring Week” in

April of that same year. Redding’s UMBC show was less than two months before his electrifying

performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967—a concert that made him a crossover

superstar in the few months before he died.

The Retriever Weekly enthused that the performance by Redding “was without a doubt the

highlight of the social year at UMBC,” though strangely took more note of the decorations for

the occasion than the music itself.

2. Quadmania 2004: A double bonus for UMBC students. Kanye West may be a globe-

trotting, always in the news, stadium-headliner now, but back in 2004 when he played at

UMBC’s Quadmania, Kanye was still an up-and-coming rapper who’d literally just rocketed to

stardom (and the top of the Billboard charts) with his first record The College Dropout and its

breakout hits “Through the Wire” and “Slow Jamz.” John Ellis ’06, history, who reviewed the

show for The Retriever Weekly, wondered if West could reproduce his layered and sophisticated

sound in concert, but concluded that “all in all, Kanye put on the best hip hop show I’ve seen in a

long time…”

Ellis also caught another performer at the same Quadmania who has had just as much subsequent musical and cultural acclaim (but perhaps not the notoriety of marrying a Kardashian), writing that renowned hit maker Pharell Williams (“Happy”) – along with his crew N.E.R.D.—“making the RAC glow with the neon greens and blues of hundreds of cell phones (the poor man’s lighter”).

3. The Velvet Underground: The musical and cultural influence of the Velvet Underground is

immense. Not only were they the first rock band to truly immerse themselves—via the

interventions of Andy Warhol and actor/singer Nico—in the world of avant garde graphic art, performance and filmmaking, but their impact on dissident writers and politicians (most notably Vaclav Havel) continues to this day.

The version of the band that played at UMBC on September 20, 1969 was without Nico and co-

founder John Cale, but main songwriter Lou Reed was playing new songs from the band’s

eponymous third record, The Velvet Underground—an LP that features classics including “Pale

Blue Eyes,” “Beginning to See the Light,” and “I’m Set Free.”

4. Snoop Dogg: Since his debut on Dr. Dre’s The Chronic in 1992, few American hip hop artists have exerted the gravitational force of Snoop Dogg. So his April 29, 2011 show at UMBC ranks as one of the biggest shows in university history. Snoop sported a Washington Capitals jersey at the show.

The Snoop Dogg was also a special event for UMBC students because of a campus-wide step show competition that offered a chance to open the show as a prize. UMBC’s Kappa Alpha Psi walked away with the honors and had a chance to perform on the same stage as one of the godfathers of rap.

5. Chicago Transit Authority (later “Chicago”): Long before their jazzy and slow dance radio hits of the 1970s (“Saturday in the Park,” “Colour My World”) and later easy listening earworms of the 1980s (“You’re the Inspiration”), Chicago was a rock band that went by the name Chicago Transit Authority—and they played two shows at UMBC behind their million-selling debut album of that name on October 19, 1969.

Chicago Transit Authority already had a smoother and more melodic sound than other jazz-inflected rock bands of that era (such as Traffic), but they also had strong countercultural bona fides. That may be a reason why a full page ad for the show appeared not in The Retriever Weekly (which did not review the show) but in the radical campus newspaper The Red Brick.

– Richard Byrne ’86

UMBC Football: Undefeated

“Why does UMBC not have a football team? Did the university ever consider having one?

The fact that UMBC does not have an intercollegiate football team is one of the defining elements for the university (and, perhaps, its social life) since its founding in 1966. The UMBC Bookstore even sells t-shirts with a Retriever paw inside a football that proudly proclaims “UMBC FOOTBALL: UNDEFEATED.” Records of various discussions of a possible intercollegiate football program are scattered throughout the university archives. While there has always been an undercurrent of interest, funding is the number one reason football never found a foothold at UMBC.

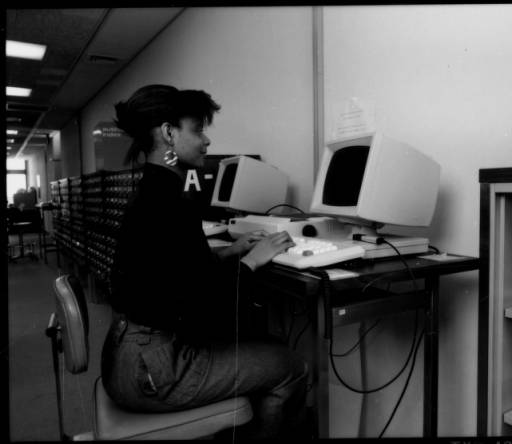

UMBC’s First Computer

“What was the first computer on campus? How did UMBC create a nationally-known reputation in the field?

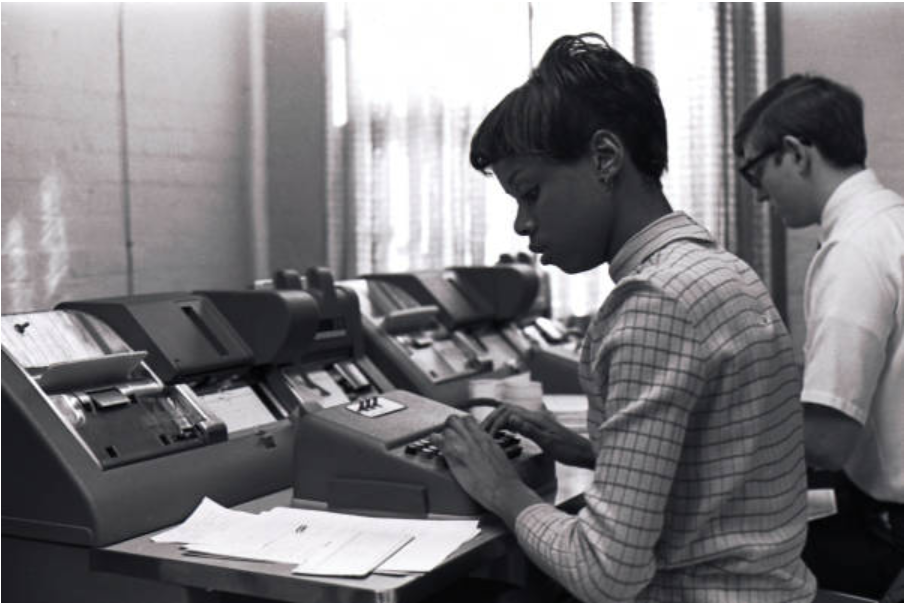

Remember punch cards? Room-sized computers? Computing centers where students would input data and wait—up to a full day—for the results? Even a university with a widely-acclaimed reputation in computer science and information technology had to get its start somewhere.

At UMBC, that beginning had roots across the university in departments including mathematics

psychology, biology, and also in the business operations of the school.

In the early years of UMBC, students didn’t major in computer science. Instead, students who pushed the boundaries of computer science were biology majors using technology to study fruit flies, psychology majors crunching numbers from their experiments, and budding mathematicians working out complex equations.

It’s also important to note that some of the roots of UMBC’s reputation as a place that encourages undergraduate research are also located in those early years of information technology at the university. Students were doing a lot of computing tasks in UMBC’s early years—keeping key elements of UMBC’s administration up to date, as well as running student projects on the first mainframe computers.

“We were all students,” says Mike Petry ’78, mathematics. “It was all students doing the computing.”

Frank Elmore ’73, biological sciences, remembers vividly the arrival on campus of a room-sized Univac 9400 computer in 1972. “The computer ran one job at a time,” Elmore recalls, adding that it could take a day to get the data processed.

As a biology major, Elmore took UMBC’s first programming class, in Fortran, that same year. He also took all the new programming courses on offer at UMBC as they were introduced during his years as an undergraduate, and then later as a graduate student and a university employee.

It was an era before students could harness individual computing power via their own personal computers and laptops, says Jack Suess ’81, mathematics, and M.S. ’85, operations analysis, who is now UMBC’s vice president of information technology.

The same big campus computers served the needs of every student, whether they were science students running experiments, or economics and accounting students studying Cobol. And everyone counted on a computer operator who would run the programs punched on stacks of cards, recalls Petry, who is now assistant director of network infrastructure at the University of Maryland, College Park.

“Students would show up with decks of these things,” observes Brian Cuthie ’84, M.S. ’94, computer science, who was one of UMBC’s earliest computer science graduates. Far from the isolation that being locked into one’s screen can bring today, the UMBC computing lab was a busy place, in that era, filled with students who had to bring their work in person.

“It had the effect of making the computer center a very social place,” says Cuthie.

Progress came at leaps and bounds. Between 1974 and 1984, computers got smaller and faster. Punch cards gave way to CRT screens. Apple computers appeared in the mid-1980s. “That’s the point where you hoped to own your own computer,” says Charles Nicholas, a professor of computer science since 1988.

Networking became more than standing around waiting for your turn. A comprehensive system called “Control Data Cyber” was installed in the library’s lower level in 1982. With 60 terminals around campus, it was the first computer generally available for use by all faculty and staff.

“That computer also had the first email system, though it could only send to people who had accounts on that system. It was the first use of email on the campus,” Suess recalls. (UMBC joined a pre-internet National Science Foundation network connecting campuses in late 1985.)

The growth also meant that the university was ready for a computer science department. Professor of mathematics A. Brooke Stephens noticed many young faculty members in other disciplines who were really computer scientists. “I could tell that they weren’t happy and they were likely to move on,” Stephens recalls.

Richard Neville, who was the dean of UMBC’s College of Arts and Sciences, was convinced, and a department formed in August 1985. Samuel Lomonaco, who was engaged in a career with the U.S. army performing lab work, arrived at UMBC and became the department’s founding chairman for its first six years.

“I looked at UMBC and I saw the tremendous potential of the institution.” Lomanoco says. “It was the wild west. The first year we were frantically trying to hire people.”

The growth of UMBC’s programs in these disciplines was cemented by the opening of a dedicated Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Building in 1992. Tim Finan, who succeeded Lomonaco as chair in 1991, called the building a “milestone” in the program’s history.

By the 1990s, Finan adds, “UMBC had more computer science graduates than any other research university in the country.”

UMBC also led in finding ways to increase diversity in an increasingly male-dominated field. Joan Korenman, a professor of English and the director of UMBC’s women’s program, was instrumental in establishing the Center for Women and Information Technology (CWIT) in 1998.

“I was very excited with the internet and what it was about. It was clear this was going to be a tremendous resource,” recalls Korenman. The center, now the Center for Women in Technology, continues to offer support and scholarships for women in these disciplines.

Today, the department of computer science and electrical engineering has grown to 1,100 undergraduate and 600 graduate students with 72 full-time and part-time faculty.

“There’s always been an incentive to hire the very best people we could,” Stephens said. “That’s one of the reasons we’re strong today. It is a good department, well balanced in various departments—artificial intelligence, cyber security, software development—and that’s another strength. No area has been overlooked or neglected.”

The growth, however, had firm roots in the earliest days of the university. “I think we were very good,” Lomanaco says. “We were teaching the real thing.”

– Mary K. Tilghman ‘79

The Founding Class

“Who was the first student to register for classes at UMBC? How many students were in the first graduating class in 1970?

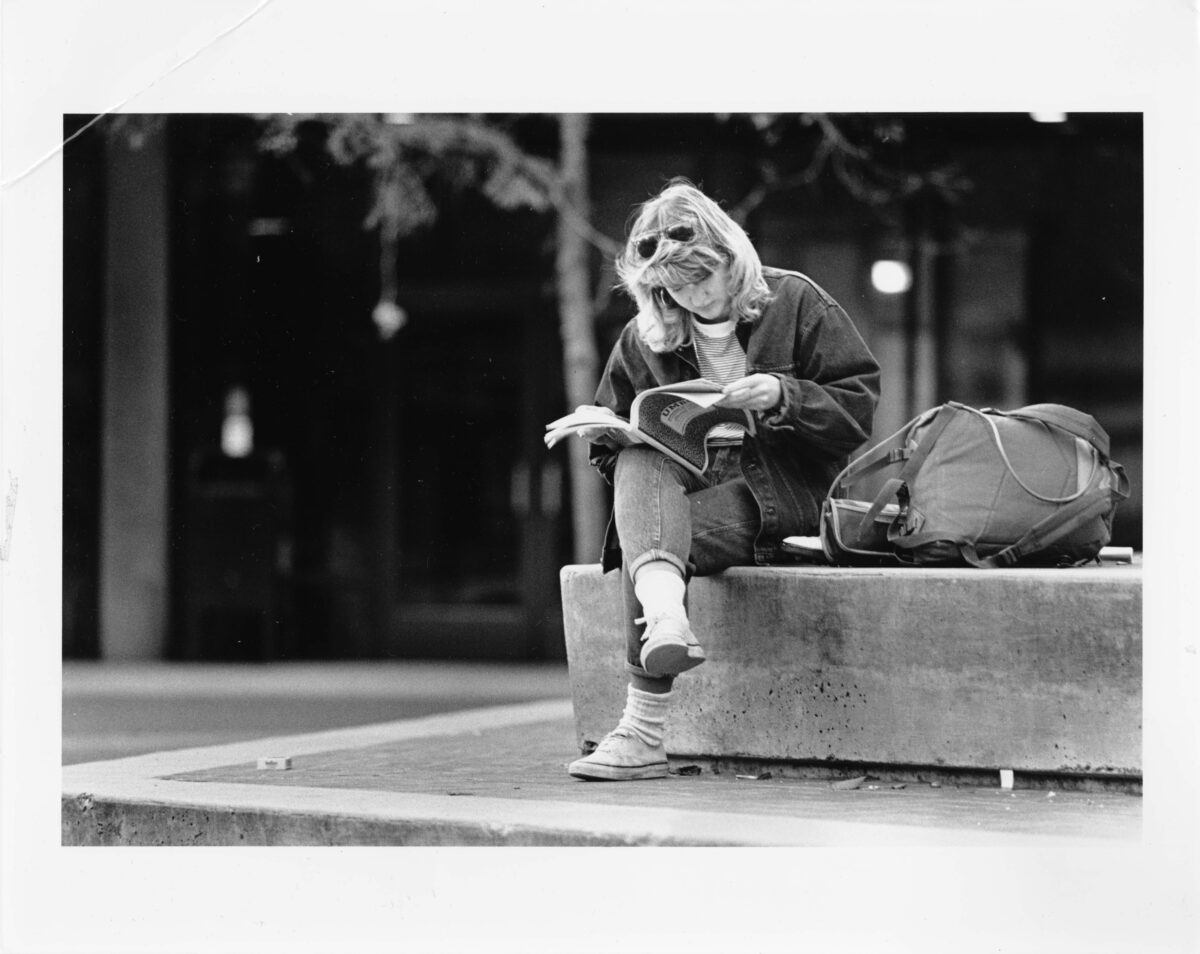

The first students at UMBC were 750 pioneers who arrived on September 19, 1966, and found three academic buildings, a campus still under construction, and a lot of mud. Some of the pathways they found were wooden boards. The Loop Road that would eventually encircle campus was years from completion yet. Who knew they would lay a foundation of hard work and determination that continues almost 50 years later?

According to the second issue of UMBC News (the student newspaper that was later renamed The Retriever Weekly), Gabija Brasauskas Blotzer ’70, English was the first student to register for classes and obtain her student identification card.

Blotzer told the newspaper that she liked the “smaller campus,” and quipped: “And to think I wanted to go to College Park.”

The first UMBC graduate was Robin Keller Mayne ’69, American studies. She received her degree one year earlier than the 239 UMBC students who graduated on June 7, 1970.

– Arooj Rana ’06

Tags: Histories & Mysteries