UMBC at the Universities at Shady Grove finds itself uniquely situated—at home within the country’s third largest biotech hub where the demand for highly skilled workers is growing. These Retrievers are filling specialized roles after graduating with the training they need to succeed in this booming industry.

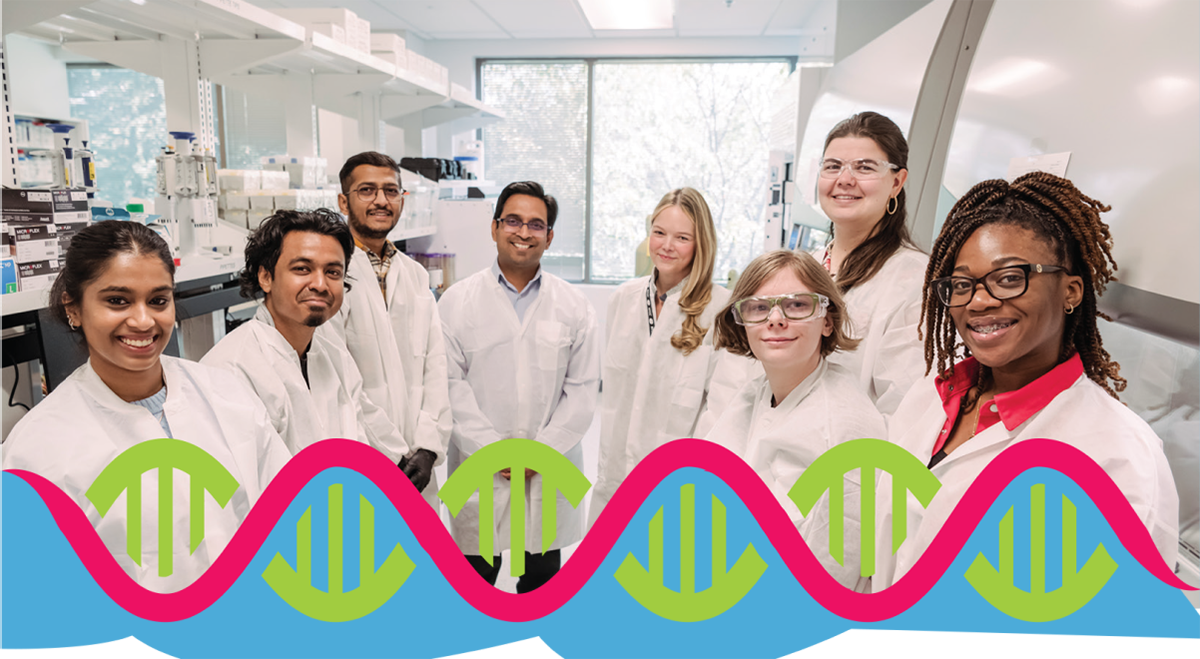

It’s an early Friday morning in the Biological Sciences and Engineering Building and nine students, working in small groups, are bustling back and forth between fume hoods and a large centrifuge. They carefully swish flasks containing cells and growth medium. The smell of sanitizing alcohol pervades the space. Neon orange test tube racks and turquoise tube caps stand out within the sterile white look of the work benches, hoods, and lab coats.

As the cells use oxygen to release energy, they produce carbon dioxide. The CO2 turns the solution yellow, indicating successful cell growth. After the experiment, students sterilize their solution with bleach for disposal; in response to the alkalinity, it blooms to a brilliant magenta. In another room, one student offers tips to her classmate on how to use a pipet more effectively, and the instructor flits between groups, answering questions as needed—but for the most part, the students operate confidently on their own.

This is a regular day in Biotechnology 303: Applied Cell Biology in UMBC’s Translational Life Science Technology (TLST) program. The program, offered by UMBC’s College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences (CNMS) exclusively at the Universities at Shady Grove (USG), a multi-institution education facility in Rockville, Maryland, is designed to offer hands-on training to prepare students for careers in the booming biotech industry in USG’s backyard.

Elizabeth Friar (left) and Samantha Petros ’23 have stayed in touch since Petros graduated.

A clear direction

It was the promise of experiential work with real-world applications that drew Samantha Petros ’23 to the TLST program. “I really liked the convenience of the USG campus, and a lot of the courses were really focused on hands-on learning,” she says. Without really knowing what the work would look like before she started the program, “I was able to try out a lot of different things in a very low-stakes environment and get an idea as to what I found interesting.”

That turned out to be cell culture work. Applied Cell Biology with Elizabeth Friar, lecturer and undergraduate program director in TLST, “cemented that benchwork is what I enjoy doing,” Petros says. From then on, “There was a clearly defined arrowhead in the direction I wanted to go.”

That was a big shift from where she started, as a film major at Montgomery College (MC). A virology course to meet her science requirement turned her on to MC’s biotech associate degree, and then she transitioned to the TLST program at UMBC. After learning some basic lab techniques in TLST classes, she landed a part-time job, where she carried out entry-level manufacturing tasks for malaria vaccines. Today, Petros is thriving as a cell culture specialist studying malaria at Axle Informatics, a contractor for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The position she’s in now traditionally requires a master’s degree, which she doesn’t have—yet, anyway. “Knowing that I have valuable skill sets from TLST—working in manufacturing, getting good connections with my professors, and going to the networking events that TLST offers—all of that compounds and has got me to where I am now,” Petros says. “I genuinely believe that I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for all of those factors, with TLST obviously being the biggest one.”

Location, location, location

TLST is a young program, but it is growing quickly. The first class—just two students—arrived in fall 2019. Friar joined in summer 2020 and began laying the groundwork for the program’s eventual growth. Today, “It’s humming along,” she says. There are currently 50 students who have declared TLST as their major. “Now we’re thinking about what we can do next. How can we expand?”

TLST is unique as the only undergraduate STEM program at UMBC without a footprint on the main campus. The location choice at USG is intentional. The Capital Biohealth Region, encompassing the District of Columbia, Virginia, and Maryland, is the third most competitive biotech hub in the country—and Montgomery County, Maryland, is the hub of the hub, boasting more than 350 life science companies and located a stone’s throw from the NIH, FDA, and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). For TLST alumni, the employment options are seemingly limitless: 80 percent of American pharmaceutical companies are within a two-hour drive, and they can expect a nearly 23 percent growth rate in the biotech industry over the next 10 years—well above the national average.

As Friar puts it, “Regenxbio is down the street. MacroGenics is down the street. MilliporeSigma is opening their new lab right next door, and they’ve now hired eight of our alumni. Soon we’ll have an NIH vaccine lab right down the street. ATCC is right down the street.” All these biotech companies need qualified workers—and TLST is providing them.

Steven Schaffer (right) and Princess Nyamali work under a biosafety cabinet in Elizabeth Friar’s Applied Cell Biology course.

Training lifetime learners

Jeff Galvin, CEO of American Gene Technologies (AGT), has hired TLST alumni and would hire more. “The TLST program seems to provide a great overview of not just biotechnology techniques,” he says, but it gives students “an understanding of the business in general. I find that UMBC students lean toward being self-motivated problem-solvers. It seems that the administration from the top all the way down promotes that idea of creating value through creative, hard work.”

Titina Sirak ’20, TLST, had a major impact at AGT. She established a brand-new laboratory certified to handle human cells from scratch, Galvin says, “And that’s not easy—there’s a lot of regulations associated with that, even economics.” While she wasn’t an expert at first, “she was able to do enough things right that the project came to life.”

Galvin emphasizes the importance of “learning how to learn,” saying, “Things are changing so fast, that it’s the folks who can adapt and become lifetime learners who are going to be the most successful.And that’s something I saw from the students coming out of TLST.”

A vision fulfilled

So far, TLST has graduated 25 students, and 94 percent of them were employed in the biotech industry within three months of walking across the Commencement stage. “We’ve had a number of really standout students who have gone on to do really great things, so I’m very excited about how it’s going,” Friar says.

Merryll Kallungal ’24 works under a biosafety cabinet at ATCC. Interns Jason Bose (left) and Tamilore Akinde (second from left) and an ATCC lead scientist observe.

So is William R. LaCourse, CNMS dean, which offers the TLST program. He envisioned the program years before the first two students walked onto the USG campus, and it came together with input from faculty at Montgomery College and five departments at UMBC.

“TLST is an innovative and practical education that combines ‘know-what’ and ‘know-how,’” says LaCourse. “It is a highly flexible program with various pathways to serve the ever-changing needs of a growing industry. TLST is where the silos of disciplines break down and cross-disciplinary knowledge is the goal—both in content and practice.”

The program is shaping up just as LaCourse and Annica Wayman ’99, mechanical engineering, and former associate dean for Shady Grove Affairs in CNMS who led TLST’s launch, had hoped. The state of Maryland is growing its biotech hub while UMBC students are gaining the skills they need to succeed in the workplace and getting well-paying jobs, and the student population is growing.

Connections that build confidence

Just as important as high-demand lab skills, students and alumni value the relationships they’ve formed with faculty. “Every teacher I had was very supportive, very understanding, very willing to work with me,” Petros says. “I think it’s important to get your money’s worth out of college, and I definitely feel like I got that and more in TLST because of the support network that I had there and my teachers.”

Petros is still in touch periodically with Wayman and Friar. “Dr. Wayman was a shining inspiration. She’s just a wonderful person. She’s so knowledgeable and always willing to help,” Petros says. The support she has and the success she’s found now have inspired Petros to look back and help those coming up behind her. In addition to USG resources, as a student Petros attended networking events offered by BioBuzz, a community resource for biotech industry professionals and job seekers in the Capital Biohealth Region. In fact, it’s how she found her current role.

Today Petros is a BioBuzz Ambassador. “I wish I had known about BioBuzz when I first started in biotech,” she says. “Now I want to be that advocate for younger students or people who are just starting in science.”

A strong foundation

“Our students come to us because they want to make a difference in people’s lives, but they don’t necessarily want to go to medical school,” Friar says. It doesn’t hurt that “we have some really spectacular facilities that are a real draw for students,” she adds.

The Biological Sciences and Engineering Building opened at USG in fall 2019 and boasts beautiful modern laboratories and classrooms plus plenty of comfy nooks for meeting with a study group or just relaxing. TLST has also received over $1 million dollars from the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Pharmaceuticals, some of which has supported further upgrades and additions to the teaching laboratories.

A flow cytometer, a machine that can detect properties of interest in up to 10,000 cells per minute, will enable a new mixed undergraduate/graduate course in flow cytometry launching next spring, for example. And equipment to practice skills like protein purification, biomanufacturing processes, and cell culture create rare opportunities for undergraduates. A required TLST course covers the wide range of instrumentation you might find in a modern biotech laboratory.

It’s normal for students to start off nervous when they use complicated and expensive equipment or work with human cells for the first time. “But by the end, they are old hands, and I think they would feel comfortable tackling anything in that lab on their own,” Friar says. “And it’s because the curriculum is really well scaffolded. We add skills as they go along, and then we repeat the old skills. The program is set up to foster growth and independence.”

Princess Nyamali stepped away from the centrifuge for a moment during Biotechnology 303 to share that the TLST coursework “is a really good foundation.” She’s currently completing an internship at NIST, and “everything I’m learning in this cell culture class is stuff I’m doing at NIST.” While it might have been daunting at first, trying so many different things across the TLST curriculum “helps you know that you want to do it,” she says, in addition to showing potential employers that you can.

TLST student Fae Switzer works at the microscope with guidance from her mentor, Emma Todd, at ATCC.

Thinking ahead

Although the two-year program initially targeted transfers from regional community colleges, “we were getting so much interest from students on the Catonsville campus, we went ahead and put it on the list of majors for freshmen applying to UMBC,” Friar says. “That’s been the fastest growing cohort in our major.”

Steven Schaffer transferred to TLST after starting on the main campus in bioinformatics. Now he is in the bioinformatics track within TLST; the other option is a biomanufacturing track. Schaffer likes that there is a strong cohort connection because everyone takes mostly the same classes together. “I would recommend TLST. It’s a growing field and the skills you learn are very versatile,” Schaffer adds.

Schaffer hopes to eventually take on a role that leans into engineering at a place like Northrop Grumman. But before that, he’s eyeing UMBC’s Master of Professional Studies in biotechnology. The M.P.S. degree offers advanced instruction in the life sciences, plus coursework in regulatory affairs, leadership, management, and financial management. Friar describes it as “a cross between a science master’s and an M.B.A.”

Academic decathletes

Soon, the confident students in Friar’s cell biology class will arrive in labs across Montgomery County, the capital region, and beyond. They will contribute to drug discovery and production, design manufacturing processes, and, eventually, lead teams and make strategic decisions for major biotech companies.

Jeff Galvin, the ATG CEO, referred to TLST alumni as “academic decathletes.” Like decathletes, they have an array of skills and perform all of them admirably. But rather than medals, they’re seeking an opportunity to contribute to positive change through their work. They’ll translate basic science into diagnostic tests, treatments for disease, and more to improve the lives of their neighbors in Maryland and those in need around the world.

ATCC’s SPARC internship program offers opportunities for TLST students to conduct meaningful work in the biotech industry. Merryll Kallungal (far left) transitioned from her internship to a full-time role at ATCC this summer.

SPARC-ing Rewarding Careers

Just 10 minutes from USG in Gaithersburg, Maryland, biotech company ATCC has capitalized on the TLST talent pipeline. Their Student Partnership and Research Collaboration (SPARC) Program requires USG enrollment and offers qualified students paid, part-time career opportunities throughout the academic year at ATCC’s research facility. As the leading developer and supplier of authenticated cell lines, microorganisms, and associated data for academia, industry, and government, a successful internship at ATCC is a feather in the cap for students pursuing a TLST degree.

Of the seven interns selected for the SPARC program this year, four are TLST students—and they are thriving. The interns praised their SPARC experience while donning lab coats, shoe booties, safety glasses, and gloves in one of ATCC’s labs—where keeping employees safe and protecting lab samples and products from contamination is mission critical.

“I love the TLST program!” exclaimed Fae Switzer, who has wanted to pursue a career in biotech since she learned about CRISPR, the gene-editing platform, as a child. Switzer, a SPARC associate biologist in the microphysiological unit, notes that things she learned in her UMBC classes prepared her for the internship, and things she’s learning at ATCC now are helping her in her classes.

Jason Bose, a SPARC associate biologist on the microbiology team, knew he was interested in biologybut not medical school. When Bose learned about TLST, he thought, “Wow, this aligns with what I want to do,” he says. “It’s been really great so far.” He even uses the basic coding skills and tricks for Excel spreadsheets that he learned in class—which at the time he wasn’t so sure about. “Yep, I use them all the time at ATCC,” he says.

Tamilore Akinde completed an internship last summer at ATCC’s headquarters in Manassas, Virginia, and now she is a SPARC intern. “I like that TLST teaches multidisciplinary skills,” she says. Being able to pivot toward different opportunities that come her way is valuable, she adds.

“The hands-on lab training provided by the TLST program has prepared students for impactful careers at ATCC,” shares Ruth Cheng, general manager and senior vice president for research and industrial solutions at ATCC. “Witnessing students like Merryll Kallungal transition from the SPARC program to a full-time role in cryobiology R&D is a testament to the power of this collaboration.”

After interning at ATCC, Kallungal graduated from TLST in May and assumed a full-time associate biologist role in the cryobiology group in June. The lab techniques she learned in TLST came in handy at ATCC, and she has already learned a lot of new things, too. “I absolutely love what I do,” she says.

Tags: cfr, CNMS, Fall 2024, Feature, MechE, shady grove, TLST