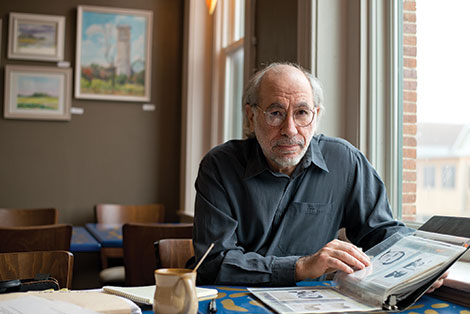

Catonsville resident Gus Russo ’72, political science, is married to the mob. And to U.S. history. He is a writer and investigative reporter specializing in the shadowy netherworld of American crime and politics. Russo has worked on 15 television documentaries for major networks in the United States and elsewhere, and he is the author of seven books – including “Where Were You? America Remembers the JFK Assassination” (Lyons Press, 2013).

The 1960s and 1970s (when I was a student at UMBC) were not just defined by musical  revolutions, but also by the tumult of politics and conspiracy – and the frantic efforts by public officials to keep secrets: Who killed JFK, MLK and RFK? Why were we in a senseless and seemingly endless war in Vietnam? Who ordered the Watergate break-in and what were the burglars after in the Democratic National Committee headquarters? What were all those silver discs people thought they saw in the sky?

revolutions, but also by the tumult of politics and conspiracy – and the frantic efforts by public officials to keep secrets: Who killed JFK, MLK and RFK? Why were we in a senseless and seemingly endless war in Vietnam? Who ordered the Watergate break-in and what were the burglars after in the Democratic National Committee headquarters? What were all those silver discs people thought they saw in the sky?

In the 1980s, I gave up work as a musician to embark upon a journey to find answers to those sorts of questions as an investigative journalist. While it’s often portrayed as a glamorous profession, the skills and tools I employ are the same mundane ones that previous generations of gumshoes have relied upon: developing and working sources, skip-tracing (locating subjects), and obtaining documentary records from courts, real estate transactions, federal archives and law enforcement agencies.

Other than giving faster access to a small percentage of available records, the digital revolution hasn’t changed the work much. Investigative reporters rarely find their best stories online. The real truth (or as close as we can get to it) often lies buried in undigitized repositories of primary source documents, or in the closely guarded memories of the first-hand players and witnesses.

It’s often hard to win the trust of those actors and witnesses to history. It requires patience and perseverance, especially in the areas that most interest me: organized crime and intelligence agencies domestic and foreign. Old school wiseguys and retired spies don’t open up their vaults (or memories) just because you sent a nice email or even snail mail. I’ve sent Christmas presents, birthday presents, get-well cards, and funeral floral arrangements. (When I’m in the middle of a project, I have “Edible Arrangements” on speed dial.) I’ve hopped on countless planes, trains and autos to take someone out to dinner and slowly gain their trust. It often takes many months. In some cases, years.

But more often than not, determination pays off. When I flew to Chicago in 2000 to take ten members of former boss Sam Giancana’s family to dinner in a suburban restaurant infamous for its parking lot whackings, I thought I must have lost my mind. But it worked. The clan introduced me to many of Sam’s still-living friends and associates – a treasure trove of information for my then work-in-progress, The Outfit.

Then there is the paper trail – and the elusive “smoking gun” that everybody wants to find. But the truth is that document trolling is painstaking and boring 99 percent of the time. (I should know: Staff members at the National Archives have told me I’ve spent more hours there over the last 20 years than any other researcher.) And for every useful page, I’ve discarded a thousand others.

It’s also difficult to find the best documents. They certainly aren’t all at the National Archives. I’ve pulled FBI files from garages and attics of retired agents. My eyes have gone blurry pouring over faded real estate quitclaim deeds. I’ve begged Congressional committee chairmen to open up investigative files stored in the Library of Congress before the traditional 50-year lockdown date expires, and appealed FBI and CIA denials more times than I can count. When the FBI tried to tell me they only held 275 pages on the mob’s longtime fixer, Sidney Korshak, I hounded them for two years to obtain the rest of what I intuited they must possess. Eventually I was rewarded with 7,500 pages delivered to my doorstep at no charge. Maybe they felt guilty about the two-year runaround.

There was gold in those files, but there were no “smoking guns.” In fact, that concept should be erased from the minds of budding and seasoned journalists alike. The only “smoking gun” proof is the literal kind: a perpetrator caught holding one of them over the body of a victim. Nothing that dispositive can ever be found after the fact. Any document can be forged, any picture Photoshopped, and any witness mistaken or corrupted.

The seasoned investigative reporter knows that the more sensational the information you have, the more corroboration is needed so that one can arrive, at best, at an approximate truth based on a preponderance of evidence. If you require concrete proofs in your life, I suggest majoring in math. Otherwise you’ll be in for one major disappointment after another.

Serious investigative work – pounding the pavement, working the phones, and poring through over documents – can max out your stamina and your credit card. But it’s the only way I have been able to find answers to the questions that dog me about the shadow powers in our country.

Plus, you make some lasting human connections along the way. (What a concept!) In the week that I wrote this piece, I had phone calls from Sam Giancana’s daughter, Carlos Marcello’s son, the man who found Lee Harvey Oswald hiding in a Dallas theater after the Kennedy assassination, and two members of JFK’s Secret Service detail.

Often when these friends call or we visit in person, I feel sad for a generation that has been led to believe that all information, knowledge and wisdom reside inside in an invisible digital server or the “cloud.” It is a failure of my generation, which created and sold the myth, and it certainly doesn’t bode well for the future of my profession.

Read the full issue of the Winter 2014 UMBC Magazine.

Tags: JFK, lyons press, Political Science, where were you: america remembers the JFK assassination