It’s no secret why first generation college students thrive at UMBC. Our network of first generation staff and faculty make it the center of their work as educators and researchers.

Sometimes, an “aha moment” appears as a bright light bulb. More often than not, though, the spark that fueled it is what really matters.

For Juwon Ajayi, that moment first happened in Nigeria. As a kid, he accidentally stuck his finger in an electrical socket. He laughs about it now, but that somewhat painful experience got his brain ticking. How was the power traveling? Why did it hurt so much?

Like many kids, Ajayi found pleasure and intellectual stimulation in Legos and dreamed of someday building his own car. When his family moved to America, he had an inkling of what he might do with his academic leanings—but college felt a bit like uncharted territory.

“It was hard. There was a big learning curve,” says Ajayi, a senior computer engineering student who started off with three years at Anne Arundel Community College while other members of his family were taking similar paths. “Everything was new. Considering my major, there was really nobody that could help me when I didn’t understand…so I basically had to try to understand it myself.”

Thankfully, when Ajayi transferred to UMBC he found a home first with the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP) program and then with the McNair Scholars community, a nationwide program focused on helping first generation students be successful in college and graduate school. Today, he’s on his way to earning a degree, and also making a difference by helping new McNairs find their way. But for many students, the hardest part is getting in the door in the first place.

“As far as the application process, I was pretty much on my own. I really just kind of winged it, which was not the best, looking back,” says Kaitlynn Lilly, a junior majoring in physics and mathematics. Lilly wound up landing on her feet despite the challenge of writing the dreaded personal essay for her college application. “That was the biggest curveball for me. It was scary—so much depends on how you come off on a piece of paper, right?”

As the first in her family to graduate from high school, Julia del Carmen Aviles-Zavala, a junior psychology major at UMBC at The Universities at Shady Grove, also found the process extremely intimidating at first.

“I was constantly feeling unsure of what class to take, and anxious as to if my classes would transfer to my major once I got to UMBC,” she says. “Honestly I was just not sure how ‘college’ worked, and I did not have a concrete idea of an outline for my next four years.”

UMBC is known for being a champion of students from all backgrounds, so it’s no surprise to find that first generation college students make up approximately 25 percent of the current student body—or that UMBC would be a huge draw for faculty and staff who come from very similar backgrounds. Fueled by their own experiences, they created the First Generation Network, resulting in programming—covering everything from social skills to financial aid to planning for grad school—and research, and a community truly dedicated to the success of first generation students.

IT’S PERSONAL

Amanda Knapp is proud of where she comes from.

As a country girl from rural West Virginia and the daughter of two parents who hadn’t finished high school (her mother later completed a BS in Nursing in 2018), Knapp took joy from the friends and ideas she found in academia. Knowing she’d need to pay her own way to college, but eager to get away, she worked multiple jobs through high school and college—including one as the bumblebee mascot for an Old Country Buffet and another loading tractor trailers with mail and heavy packages until the wee hours of night.

It was tough work, but it gave Knapp the freedom to make important connections at SUNY Buffalo, like managing a 3,000-member ski club and joining the women’s rugby team. There, not only did she find friends and professors who helped guide her, but a pathway to her current work as associate vice provost and assistant dean for Undergraduate Academic Affairs at UMBC.

“Working in this field is a way for me to give back to a profession that literally changed the course of my life,” says Knapp, whose position gives her direct ways of helping students via student success efforts, the Academic Success Center, and the year-old First Generation Network.

“To be able to help someone remove those barriers so they don’t have to face them—or just know that they have someone who cares about them—is what makes our campus so special. There are so many of us on this campus.”

Faculty and staff who are first generation college graduates themselves often can see the issues their students are facing before the students themselves. That means a big part of the work is giving students tools they didn’t even know they yet need, says Michael Hunt ’06, M13, mathematics, director of the UMBC McNair Scholars Program and a current doctoral student in the Language, Literacy & Culture program at UMBC.

Hunt describes a common scenario: A student applies for summer research opportunities all over the country, and is accepted by a second choice location. The student wants to know if they have other options, but the first place is giving them a deadline to respond. The student stresses, not knowing what to do.

“So, what do I do? I say, ‘Well, did you email them? Did you pick up the phone and call them?’ And the student says, ‘We can do that? I’m allowed to do that?’” says Hunt, a graduate of both the McNair and Meyerhoff Scholars Programs. “So you get them to sort of recognize what they are able to do and help them take that to the next level. And that’s what it is for us. It’s okay; I’m going to show you how to play the game.”

Hunt has always been an outgoing person and educator, warm and affirming. In the age of social distancing, he and the McNair team have upped their game in new ways, offering fun and informal ways of socializing, including web-based “hype sessions,” student group chats to provide both academic and social structure.

As a fellow first generation college student, Bill LaCourse, dean of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, loves to see and hear about these projects working for students. Growing up in Connecticut, as the first in his extended family to attend college, LaCourse worked as a bike mechanic, a hospital laundry washer, a cook, and a stock clerk in order to save up for college.

Along the way to his eventual doctorate in chemistry, LaCourse learned how personal relationships and mentorship can really make the difference for students trying to figure out their options.

“We are all mentors for each other,” he says. “We are all role models to somebody whether we are a good role model or a bad role model. That’s something that’s important to have because as I went forward, I had my good ones, but I had my bad ones as well.”

Looking back on his own experiences, LaCourse sees value in what he learned. Today he works to create inclusive environments for underserved students in his college and beyond.

“The whole mission for me is to have people not make the same stupid mistakes I did,” he admits. “They don’t have to waste their time and learn everything the hard way. I’ve done that. I’ve come through the brush and the copses to get where I needed to go. They can have it better because of what I went through.”

LOOKING DEEPLY AT CAUSES, SOLUTIONS

If personal relationships are one side of the student success coin at UMBC, the other is research.

In her work with Knapp in the Academic Success Center (ASC), Delana Gregg, M.S. ’04, instructional development systems, Ph.D. ’19, language, literacy, and culture, hears about student experiences directly. As director of assessment and analysis and a first generation student herself, Gregg’s position also lets her combine her interests and daily work into her research.

Driven by UMBC student data and surveys, Gregg’s recent doctoral dissertation focuses specifically on the experiences of first year and transfer students who are the first in their families to attend college. The goal? To determine which experiences on campus—such as service learning and internships—make the most difference, and why.

“After they had these community-based experiences, what students said was they felt socially connected, they felt like they learned how to work on a team….And they felt academically connected,” says Gregg, feeling like they were using what they learned. “And this gave them a sense of belonging. They understood what their purpose was. It wasn’t just like ‘I’m going to college because I’m supposed to.’ It’s ‘Oh, I see myself in a career that I could do with this degree.’”

As the youngest of 11 children in a low-income family, and a McNair alumna herself, McNair program coordinator Antoinette Newsome works one-on-one with students as they navigate their classes and relationships with professors, as well as plan for a future in graduate school. Because of her background, Newsome feels a deep pull to study the ways this work impacts first generation college students, and the responsibility of institutions in the retention of these students.

“It is imperative for first-generation college students to find faculty and staff who come from similar circumstances because oftentimes we feel alone in navigating this huge higher education system,” says Newsome, who is working toward a Ph.D. in Student Affairs at University of Maryland, College Park.

“Knowing that your professors and/or staff members will understand what it means when you have to miss class due to taking care of a family member or maybe have to be late since you live off campus and work multiple jobs is important,” says Newsome. “Life happens to our students and knowing that faculty understand the reality and can provide some support through it is very comforting for these students.”

At this fall’s Hill-Robinson McNair Lecture, Jasmine Lee, director of Inclusive Excellence & Initiatives for Identity, Inclusion, & Belonging in the Division of Student Affairs at UMBC, reiterated the need for mentors of color for students of color, especially within the first generation community. As a product of the Eastern Michigan University McNair Scholars program, Lee’s doctoral research uses a storytelling-based approach to identify common factors for academic resilience among certain groups of underserved students—Black, first generation, and low income—at predominantly white institutions.

“Separately, any of these challenges or barriers can feel overwhelming. They can lead to hopelessness and can lead to academic disengagement. Take them together, and it is absolutely no surprise that the fourth, fifth, and sixth year graduation rate of these populations continues to fall well below the national average,” says Lee.

However, she found, when educators take an anti deficit approach to their work, seeing the value in cultural wealth and personal stories, they can begin to face a number of common barriers to success: business continuity challenges, lack of nurturing supportive resources, and lack of representation. For Lee, the research plays into her everyday work at UMBC.

“Students need affirmation, support, and advocacy,” she says. “Affirmation shows up in our micro-affirmations. Seeing them, the sense of mattering, that they belong, that when I see you across the hallway, I smile. That I remember things about you because you matter to me.”

All of these findings help our students, these researchers say. That’s a goal and an imperative, says LaCourse.

“We need to scour the data to look for the people who have excelled without anybody’s help and give them some reward for that,” he says. “And then in the meantime, we can focus our attention on those who need it—and my thing is that everyone has potential. We let them through the door at UMBC, however we do that, we are morally and ethically committed to give them the best education possible. That’s our job.”

NETWORKS OF SUPPORT

Finding the right people in college is so important, just as much for guidance and lifting one’s spirits as for having a community to cheer you on when you’ve succeeded. That’s why UMBC offers a variety of groups for new first generation students, no matter what their background or where they hope to go.

In addition to the McNair Scholars, for 30 years, UMBC—now within the scope of the Office of Academic Opportunity Programs—has run several federally-funded programs offering services and mentorship to underrepresented minority students, as well as low income and first generation students. Educational Talent Search covers grades six through twelve, and Upward Bound focuses on high schoolers.

Corris Davis ’98, biological sciences, M.P.P. ’19, M6, who oversees the office, intentionally hires first generation students as staff because it helps the pipeline of support overall.

“My office sits in a really unique place,” says Davis, who is also pursuing a doctorate in public policy at UMBC. “We’re able to see what goes wrong in K-12, and we’re able to try to correct those things in some of our participants before they get to higher ed.”

Similarly, via the Achieving Collegiate Excellence and Success, or ACES Montgomery, program, senior del Carmen Aviles-Zavala received assistance en route from high school, and through her two years each at Montgomery College and UMBC at Shady Grove, respectively. Through the program, she also made friends with other first generation students, she explains.

“Any question I had about FAFSA, registering for classes, or keeping track of my credits, ACES was always there to guide me,” she says. “Although their profession is to help students, I always felt such genuine interest in my academic wellbeing. I truly have felt that my coaches want me to succeed, and I have been able to do just that because of them.”

Knowing that there are plenty of first generation college students beyond the ones directly affiliated with McNair and the other programs, Davis and others on campus started a First Generation Network to open up mentorship opportunities and connect faculty, staff, and students on campus. Even during the pandemic, the group has offered monthly virtual brown bag sessions, and a virtual First Gen Day celebration.

“We’re starting out small, but we’re always thinking, ‘What can we do to serve more?’” says Davis. “We’re growing into something we hope will be more structured. The goal is to just help build this community…when students can find people who are willing to go out of their way to make sure they’re successful, that’s a wonderful thing.”

SIGHTS SET ON SUCCESS

Once computer engineering student Juwon Ajayi got himself on track with the McNair program, his focus went from his own needs to those of others. As the lead McNair Student Ambassador, he checks on fellow scholars at least once a week. He’s even created detailed spreadsheets to help his friends track their grades and applications to graduate school—something he had to figure out on his own.

“When I was at my community college, that’s when I started developing an idea of trying to help other students mainly because if I am struggling at it, there’s a 100 percent chance they are probably struggling at it, too,” he says. “We’re kind of like a community helping together. So as an ambassador, if it’s something that I can help with, I will help with it.”

Senior psychology major Ting Huang has found assistance from the Shady Grove community as well as the McNair program, even from afar.

“At Shady Grove, many of the faculty and staff helped promote a diverse environment that made me feel comfortable reaching out for help. I think that that was the most important support I have gotten as a first-gen student because I remember being very afraid to reach out when I was in Montgomery College and I felt so afraid applying for transfer to UMBC,” she says. “But now, with the help of McNair, my mentors, and other campus resources, I’ve built confidence and I’m applying to graduate school in December.

While classes were happening in person physics major Kaitlynn Lilly found a special way of passing along the help she’s received – by tutoring students at Arbutus Middle School. The four hours a week she spends working on math with sixth graders is good practice; someday, she hopes to be a professor.

“I really like having an impact on somebody. And so I think it’s really – I think it’s a fun challenge to be able to take what you know and explain it in a way that somebody else will be able to understand. And just seeing the change in students as you work with them for a long time is really, really important to me,” she says. “And … means more than any accomplishment that I could have for myself, just seeing somebody else be able to go through those same things.”

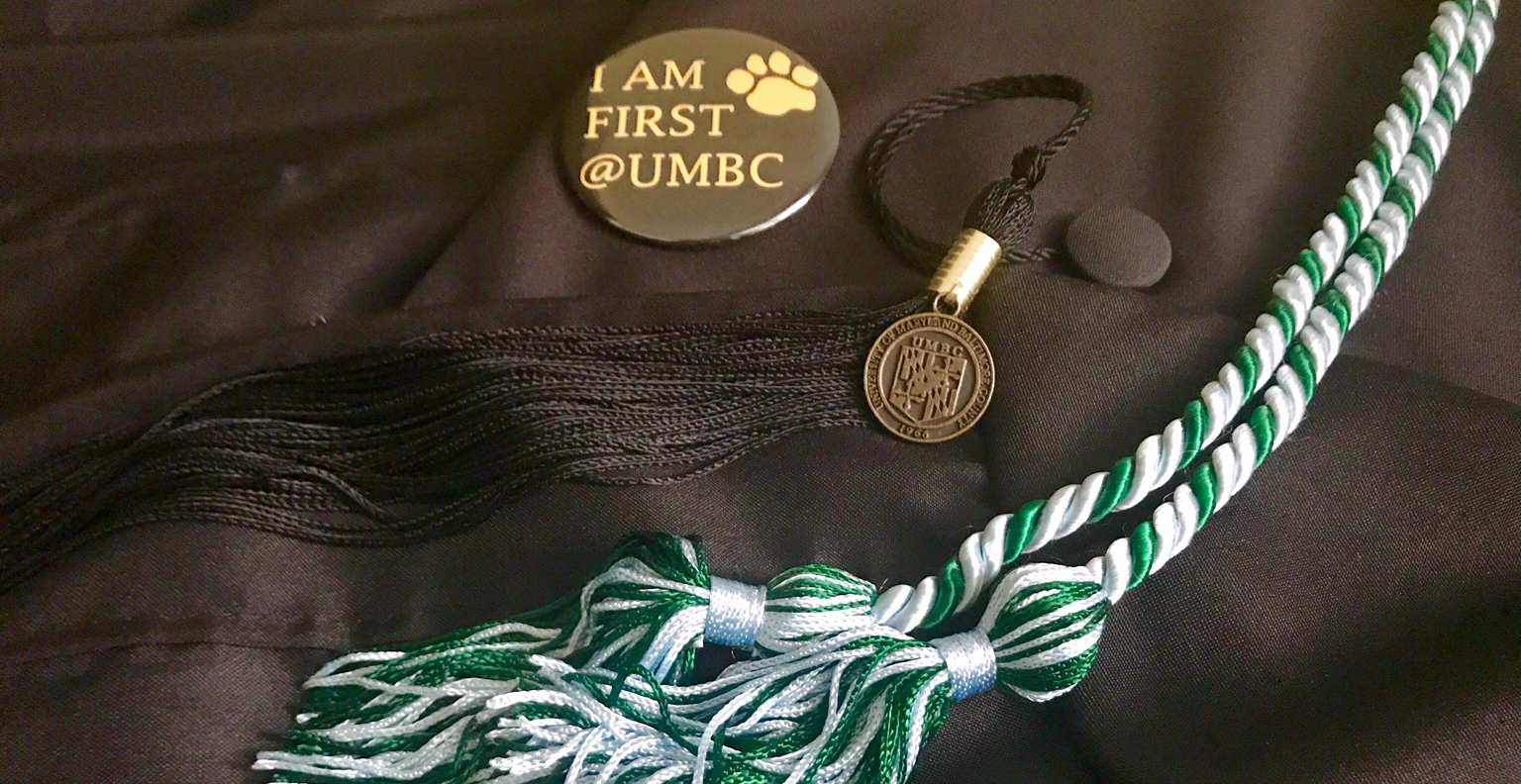

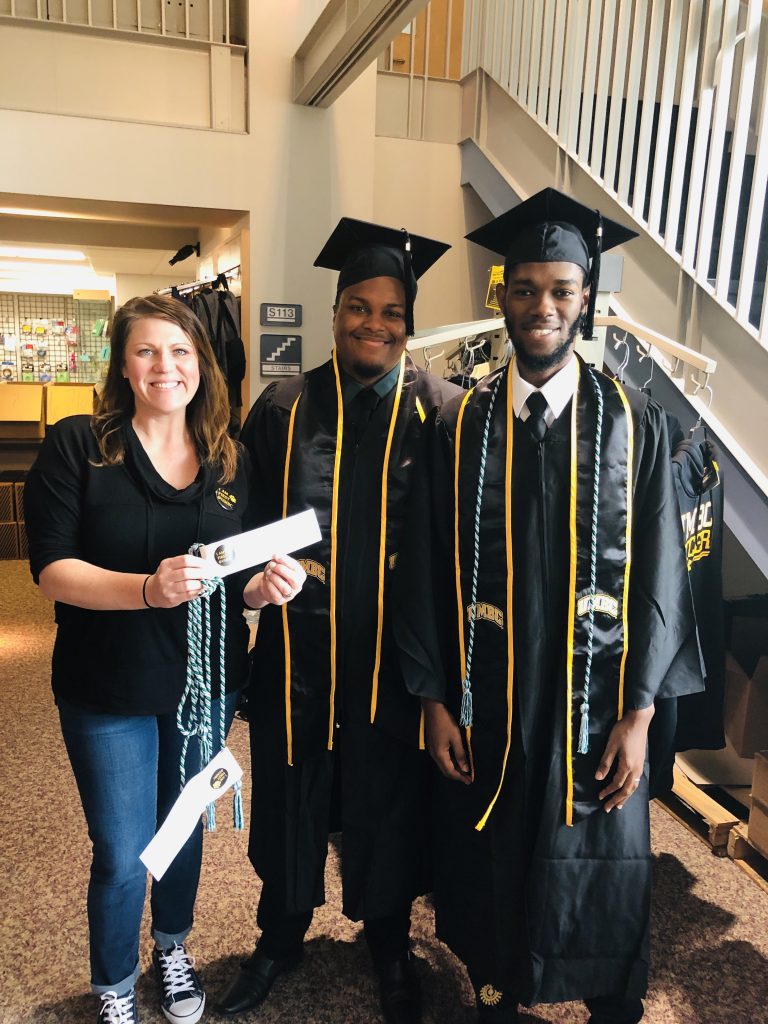

Making it into college is one thing for first gens; finishing is quite another. So, when commencement day comes, UMBC’s first generation community likes to make a big deal of it. In December 2019, the last in-person commencement before the pandemic forced the ceremony to go virtual, Knapp posed with a group of graduating seniors wearing special green and white cords and “I am First Gen” pins.

Knapp gets a bit verklempt just thinking about it. Maybe that’s because she can see herself—and the journey—in those students.

“It’s just such a special moment for everyone,” says Knapp. “They’re so excited, like ‘Wow, you’re honoring me.’ And then we get to tell them how proud we are of them.”

Learn more about the First Generation Network here.

Tags: McNair, professorsnottomiss, ShadyGrove