The ways that universities physically store knowledge – and allow the community to access it –are at the heart of the enterprise of learning and research. What is a university without its library – and its mainframes?

build the university’s library.

The UMBC story usually begins with its doors opening for classes in September 1966. But, that’s skipping ahead a chapter. Or 25,000 chapters, to be precise.

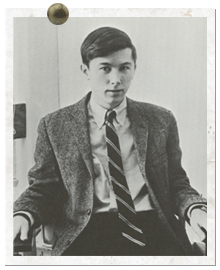

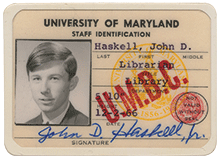

On February 1, 1965, UMBC’s very first employee arrived on campus. Fresh out of graduate school and six months of active duty in the Army Reserves, 24-year-old John Haskell was hired to build what we know today as the Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery.

Haskell, now 74, recalls UMBC at its beginnings: “There was literally nothing. It was just [the] Hillcrest [Building], which at that point was virtually abandoned by the state.”

Indeed, Haskell spent his first months working in the basement of McKeldin Library at the University of Maryland, College Park, tackling the daunting work of ordering thousands of books and journal subscriptions – as well as the shelves to store them.

He also met his future wife, Mary, who happened to sit a desk over in the McKeldin basement. “My wife and I kid about this,” he says, “but when we were dating, sometimes we would spend our time alphabetizing cards” in Hillcrest, where he eventually moved his office.

“One thing I remember,” he adds. “We didn’t have to worry about how much things cost, because the university’s philosophy was we’ve got to get this library going, and we’re going to do it right.”

Haskell pulled titles from a “New Campus” list created by the University of California system, and created an ordering system based on conversations with the faculty. He also decided to dispense with the standard somber black binding for the periodicals – instead opting for a “less stuffy” rainbow of colors to distinguish between subjects.

When the doors opened for class, Haskell had amassed 25,000 volumes, hired several employees – and a well-earned sense of accomplishment. He loved seeing students in the space.

He remembers vividly a moment during the Vietnam War, when a group of students who called themselves the Gorilla Band asked him if they could “march through the library with trashcan lids…and get people to come out on the front lawn for a rally? And I said sure,” he recalls. “Most librarians in that day would be horrified by that. That’s not how I approached things.”

Haskell left UMBC in 1969 to earn a doctorate and subsequently worked in special collections at the College of William and Mary. Today, the library he founded boasts more than a million bound volumes, nearly two million photographs and slides and other resources, as well as a year-round gallery.

“The best part of it all was nobody ever said ‘We’ve always done it that way,’” Haskell recalls. “Since you didn’t have anything, you could just decide how you wanted to do things,” he said. “It was fun.”

Computers and the information that pulses through their networks are just as crucial as books for a university – if not more so, since they also power the administration of the institution.

The story of how UMBC’s information systems infrastructure was built is also a story of people with the foresight to explore new territory, and the educators whose positive examples helped others blaze trails after them.

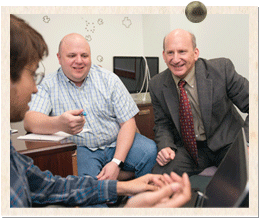

That is why Jack Suess ’81, mathematics, and M.S. ’95, information systems, says that experiences from his student days still greatly influence the way he leads UMBC’s Division of Information Technology (DOIT).

Suess’ journey started in 1976, his freshman year at UMBC. He recalls that a geography professor, John Starr, sensed that he was holding back academically. “He had this booming voice and he was just an amazing teacher,” says Suess. “And one day he said, ‘Are you really giving it your best effort?’ And I said no…and he goes, ‘Well, why don’t you try giving it your best effort? I really think you could do it.’”

The conversation struck a chord with Suess, who also took a chance on a programming class because a friend told him “the computer might be helpful someday.”

Suess excelled in that class and others, and leapt into the world of information technology, later taking jobs in the computer center and as a teaching assistant. Those positions opened his eyes, brought him out of his shell, and unlocked a long career at UMBC.

Shortly after graduating in 1981, Suess took a job as programmer analyst on UMBC’s very first mainframe computer, a 2,000-square-foot behemoth housed in the basement of the library. Until 1982, all of UMBC’s computing had come from College Park, so this was the first of many big moments in computing both for the university and for Suess.

“This was really sort of the start of UMBC building out into its computing identity,” he recalls. In the years that followed, Suess continued to help shape the university’s information structure, from the implementation of early networking and Internet in the mid-80s, to the launch of the first campus website in 1994, and the very first campus portal combining business and academic services in the late 90s.

Suess did it all while nurturing a growing team of student and alumni talent – just as he had been nurtured.

“[Suess] has always been supportive of students, giving them opportunities to explore and try new things; and offering leadership opportunities, also,” says Kevin Joseph ’87, computer science, a longtime employee of DOIT. “The culture Jack has built…provides a place that the students see themselves fitting in and being valued, [and] as a place to work after they graduate.”

That dedicated and entrepreneurial base allows DOIT to remain nimble in the face of growing demands.

“What’s always been amazing about UMBC is we were trying and usually succeeding at doing things we had no – well, things we should never have thought we could do because it’s insane,” explains Suess. “All along, we were doing stuff that very few places were doing. And it a great group of people who were really innovative and doing fun stuff.”

— Jenny O’Grady

Tags: Winter 2016