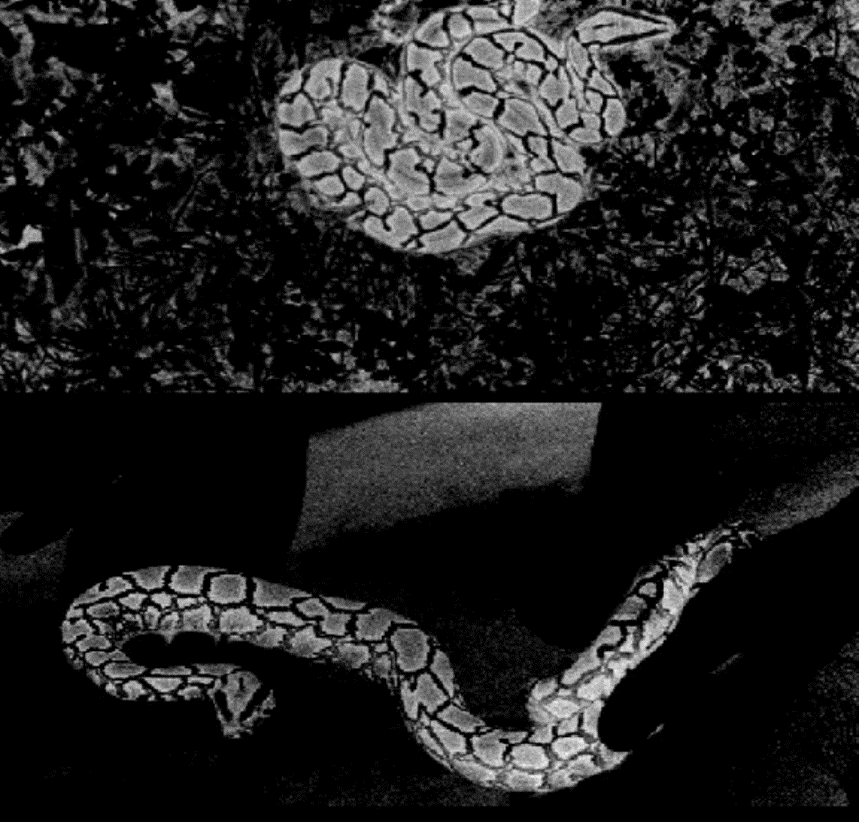

Jennifer Hewitt ’18, physics, didn’t know that her casual interest in reptiles would lead to a one-of-a-kind study that helps snake hunters track down Burmese pythons in the Florida Everglades.

Hewitt, a doctoral candidate at the University of Central Florida (UCF), and fellow researchers at UCF CREOL, The College of Optics and Photonics, are using near-infrared (NIR) cameras to detect and identify Burmese pythons. The snakes, which can reach up to 26 feet in length and 200 pounds, have threatened the native species in the Everglades since they were first introduced into the region in the late 1990s by the hands of irresponsible exotic pet owners and breeders. Since then, previous studies have shown that pythons have caused a drop in the number of common native species—such as raccoons, opossums, and rabbits—by more than 90 percent.

Working around natural camouflage

Hewitt, who is a part of CREOL’s Infrared Systems and Imaging Group, led the python-tracking study, which was published in Applied Optics earlier this year. Her work is paving the way in decreasing the pesky python problem in the Everglades, while further advancing optics research and system design.

The Maryland native joined the project to build off of the work that was already being done in analyzing the spectral reflectivity characterizations of pythons—which would then allow the NIR camera to effectively circumvent the python’s natural camouflage.

“We went to a local zoo and took spectral measurements of the [snake] hide so that we could take a look at their reflectivity,” said Hewitt. “We compared that to similar spectral measurements of plant life, both the living and dead, that are local to the region. We noticed that there is a pretty good contrast between the pythons and the background in the NIR starting at around 750 nanometers and longer.” At lower ranges, said Hewitt, there isn’t very much visible difference between python and plant.

Hewitt collected images of pythons in different locations and with different background scenery. She then conducted a human perception test on volunteers to evaluate the effectiveness of the system she developed.

“For both day and night conditions, volunteers were able to detect the pythons further away with NIR than with visible imagery [basically, the naked eye]. From here, we are continuing to fine tune the camera system to further improve the detection rate,” Hewitt shared in a press release announcing her published study.

The study’s results showed that the enhanced contrast from the NIR enabled participants to detect pythons at 20 percent longer ranges than the use of visible imagery. Hewitt’s research could potentially be later used to develop automated snake detection systems.

Early beginnings in optics

Hewitt is no stranger to capturing and analyzing imaging data. While pursuing her undergraduate degree at UMBC, she worked in Eileen Meyer’s physics lab studying black hole imaging and the structure of jets emitted from the black holes. Meyer, associate professor in UMBC’s Department of Physics, advised Hewitt during her undergraduate career and immediately recognized her aptitude in understanding the physics and mathematics of interferometry, which is used in astronomy for radio-wavelength observations.

“I first noticed [Hewitt’s] aptitude in my junior optical lab course, where she wrote the most beautiful lab reports I ever saw in the course. After she joined the research group, Hewitt very quickly mastered the ‘art’ of analyzing astronomy images made at radio wavelengths,” said Meyer. “She made so many useful images for our archive that we still regularly use them today.”

Even though Hewitt shared that she was initially interested in being an astronomer, Meyer encouraged the young physicist to explore optics graduate programs after taking notice of her success in optics research.

“I knew right away from seeing her work in my optics lab that she had talent for research—conscientiousness, clarity of thought, and an analytical mind. I am beyond happy to see how well Hewitt is doing,” Meyers said. “I am particularly grateful that UMBC supports undergraduate research so well.”

Hewitt was a 2017 – 2018 recipient of UMBC’s Undergraduate Research Award for her work “Characterizing Hotspots of Extragalactic Jets and the Connection Between Jet Speed and Let Power.” While her current research pursuits have gone in a different direction, Hewitt shared that she “liked what I was doing in astronomy, but I very much prefer the field work that I’m doing as a more closer-to-earth scientist.”

Supporting a growing demographic in physics

Hewitt doesn’t take it lightly that she’s among the small percentage of women who have a career in physics. According to the American Institute of Physics, in 2017, women earned 21 percent of physics bachelor’s degrees and 20 percent of physics doctorates. At UCF, Hewitt said women comprised about one-third of the physics classes.

Hewitt’s mother, Jeanne Toussaint, works in systems engineering and shared with her daughter the drastic difference of the number of women currently in physics compared to when she was a student.

“I find myself doing the mental tally of how many of us women there are,” said Hewitt, “and my mother says that’s already far better than what I used to have. She said that maybe one or two women were in her classrooms, and sometimes she was the only one.”

Hewitt’s hoping to add to the growing demographic of women working in her industry. Her snake-tracking research will be used by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission on a project that will possibly assist professional hunters with locating Burmese pythons. Her work has already garnered attention from major research entities. Hewitt was awarded a scholarship by the U.S. Air Force and will work in the Air Force’s research labs after she graduates from UCF.

“It’s going to be a huge change from what I’m currently doing because most of my research has been applied to single band imagery,” Hewitt noted. “I’m hopefully going to be using a lot of the stuff that I’ve learned for overall general system design to assist with some of the research that they’re doing in the labs.”

— Adriana Fraser

Header image: Portrait of a Burmese Python, Python bivittatus curling on a branch.

ID 153913085 © Dwiputra18 | Dreamstime.com