Everyone who’s ever met Kizzmekia Corbett ’08, M16, biological sciences and sociology, gets it.

Sue Florence, one of the few Black teachers in the Hillsborough, North Carolina, school district where Corbett went to elementary and middle school, got it. Rhonda Brooks, Corbett’s mother, remembers Florence saying, when Corbett was in third grade, “She’s got a gift. You’d better seek into it.”

Florence’s comments pushed Brooks to make sure expectations were high for Corbett in school, and to encourage—no, require—15-year-old “Kizzy” to find a scholarly internship rather than a position in retail when she wanted a summer job in high school.

So, at her mother’s behest, Corbett got involved in Project SEED, a program that offers research experiences to talented high school students from underrepresented groups in STEM. Her first program mentor was James Morken, who was on the chemistry faculty at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill at the time.

He got it, too.

“When Kizzy started in my laboratory, she didn’t have much hands-on research experience, but she had loads of curiosity, a drive to learn what she didn’t know, and a very strong work ethic,” Morken says. “It was abundantly clear she would be successful in whatever she chose to do.”

Today, Corbett is an assistant professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, after leading the team behind the successful effort to create a vaccine for COVID-19 at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Working with the pharmaceutical company Moderna, Corbett’s achievements on the global stage benefit all of us. Now, we get it, too.

“She can do anything”

As a Meyerhoff Scholar and NIH Scholar at UMBC, Corbett worked in Barney Graham’s lab at the Vaccine Research Center at the NIH. He’s also her boss today.

“Kizzmekia’s spirit was noticeable even from a young age,” Graham says. “New people who come into the lab have always quickly realized that she was a person who had bigger things in her future.”

Corbett met Jessica Kelley, a UMBC assistant professor of sociology at the time, when Corbett took her Introduction to Sociology course. “She was a standout in that large lecture class from the beginning,” Kelley recalls. Later, Corbett took Kelley’s course on applied community research, and conducted research with Kelley as part of a National Institute on Aging study on healthy aging in diverse neighborhoods.

The work with Kelley inspired Corbett’s double major and her approach to all of her future work. Corbett even became the only undergraduate enrolled in one of Kelley’s graduate-level courses. “She kept the graduate students on their toes,” Kelley says.

“When she’s got her mind set on something, it’s set,” Brooks says. “She can do anything.”

A leading role

Today, Corbett has proven them all right. As the scientific lead of the Vaccine Research Center’s coronavirus team at the NIH, she developed a new technology for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine and others, and as a result, she has played a leading role in one of the most important measures to end the pandemic. She has also become the first Black woman in the world to create a vaccine.

Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and one of the most trusted voices about the pandemic around the world, described Corbett as “widely recognized in the immunology community as a rising star,” when he nominated her for TIME magazine’s TIME100 Next list. Based on her leadership of COVID-19 vaccine development at NIAID, he added, “Her work will have a substantial impact on ending the worst respiratory-disease pandemic in more than 100 years.”

People drive the research

Perhaps just as important as her scientific accomplishments, Corbett has burst onto the public stage as the face of a diverse and rising generation of talented scientists who will transform the world. She is a stellar science communicator, explaining the vaccine and the virus in highly accessible ways to media outlets, her family, two U.S. presidents, and more. She is an inspiration to children who may now imagine becoming scientists.

“Dr. Corbett’s voice has been particularly important this year,” Graham says, “and going forward, her ability to inspire and to educate and motivate young people to see science as something feasible and even to see science as something fun will be part of her legacy.”

And yet, amid her newfound celebrity status and her vast scientific acumen, somehow she has managed to remain unabashedly human.

“I am still Kizzy. I’m still the little girl you met when I was 17 and being recruited into the Meyerhoff program,” she told UMBC President Freeman Hrabowski during a conversation in February 2021, when they were both being recognized at the Kaiser Permanente and Reginald F. Lewis Museum 2nd Annual African American Health Care Awards.

“Actually, before a scientist, I’m a Christian, and I’m sassy, and I’m bright, and I’m fashionable…” she says, “and I’m Southern, and I’m empathetic, and I’m all of these things that make me into this person, that make me a better scientist. I think that is the most important part of the story—that people drive the research.”

The genuine thing

First there was Sue Florence. Then there was James Morken and others with the SEED Project. All through her childhood, there was her mother, Rhonda Brooks, cheering her on. Combine that support structure with Corbett’s own deep-seated determination to succeed, and by the time she was looking at colleges, Corbett had lots of options. But when she, her parents, and her grandmother visited UMBC, it felt like home. The first reason? The grain silo along UMBC Boulevard.

“It reminded me of being back at home in the country,” Brooks remembers. When they began touring campus, Brooks thought, “Oh man, this is really her,” but, “I needed her to see it was her. So I didn’t even say anything.” There was no need. By the end of Meyerhoff Selection Weekend in 2004, Kizzy was glowing.

Beyond the welcoming silo were all the welcoming faces. “Everybody was so friendly,” Brooks says. “You think when you go visit campuses that people have to be this way because they’re trying to get students to come, but as a person who’s been in the education field for so long, I can weed out who’s genuine and who isn’t.” And, Brooks says, despite the emphasis on Meyerhoff cohort numbers, of which Kizzy belonged to M16, “it just felt like she would be not just a number.”

Equaling the playing field

In the February conversation with Hrabowski, Corbett recalls her father telling her that she should “go where she would be loved.” UMBC became that place.

Asked to describe the value of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program, she said, “It is simply one word: resources. It is equaling the playing field for people who have generally been under-resourced, and those are communities of color and people from underrepresented minority groups. And the Meyerhoff Program does that.”

The Meyerhoff Scholars Program, founded in 1989, is considered the gold standard of programs designed to support students from underrepresented groups in STEM. Hundreds of alumni have gone on to standout careers, including U.S. Surgeon General, Baltimore City health commissioner, and professorships at the nation’s top-tier universities.

The Meyerhoff Scholars Program “is a place where every single person was special and would be loved. The goal is not to fail you out, but to lift you up,” Corbett says. And for underrepresented students in STEM, living in a world that too often still doesn’t expect people who look like them to excel as researchers, the Meyerhoff Program “provided a niche for us to just be, to be comfortable, and to just thrive.”

A mother’s touch

It wasn’t always easy, though. Brooks remembers when Kizzy received her first C. “Being on the phone with her just didn’t help,” Brooks remembers. “So I got in my car, and I drove all the way to Maryland. I was trying to tell her it was going to be alright, but it was just heartbreaking, because she never had that C. I told her, it’s gonna be tough—you might get more than one C.”

Even world-class, world-saving scientists sometimes get Cs and need their moms.

And even now, Brooks is ready to support Corbett as she navigates this new chapter in her life. “If she needs me now, if she’s feeling stressed,” Brooks says, “if she picks up the phone, I don’t care what time of night it is, I pick it up.”

On Corbett’s college bedside also sat a Bible—another lasting connection to her family and her faith, which Corbett brings up often in her interviews. Brooks gave each of her children a Bible as they left for college. “I say take this Bible with you. Even if you don’t look at it, keep it next to your bed. I don’t care if you don’t open it. But if you touch it, it will make you feel a whole lot better.”

Corbett and her mother, though apart during the pandemic, have stayed connected by attending online services from the same church in Texas. Their first travel plans post-pandemic? A trip to attend the service in person.

Lifting others up

Whether it’s her faith, an innate empathy, 35 years of experience as a Black woman in the U.S., or other factors, Corbett’s dedication to lifting people up goes far beyond her work in the laboratory. Her commitment to equity has demanded that she speak out to address vaccine hesitancy, especially in communities hit hardest by the virus, and champion the participation of minorities in science and research, both as scientists and as participants in clinical trials.

“She has always, even as a young student, brought an energy and curiosity and love of science that made our lab a better place,” Graham says. “She has also always been very devoted to making things better for people around her, particularly younger people coming behind her.”

Brooks says that Corbett has always had a selfless nature. One day she brought home a classmate who had no place to go after school and asked if she could stay with the family. Brooks was uncertain at first, “but we did it,” she says. “And we’ve been taking kids in ever since.”

Fighting for the public good

Corbett’s study of sociology at UMBC enhanced and sharpened her innate desires to help people and promote fairness into a commitment to consider social factors throughout her scientific career. For example, when the Moderna vaccine was in clinical trials, Corbett pushed hard to make sure that there were more people of color among the study population.

“You have to start things equitably to finish them that way,” she told Hrabowski at the February event. “We slowed down the phase three clinical trial until we got to a point where we felt the numbers were respectable. We wanted 13 percent, to represent the proportion of Black people in the country,” she said, but they didn’t quite make it. Still, she says, “I have other vaccines heading into trials, so we will take care of it then.”

Kelley, her sociology instructor and research mentor at UMBC, reflects on how Corbett has developed over time. “Kizzmekia’s training in both biology and sociology has helped her become both a scientist working at the cutting-edge of vaccine development to provide a universal public good and a humanist who understands that historically and structurally not all groups have had access to these public goods,” she says.

(left: Corbett at a Rally for Medical Research event in Washington, D.C.)

Corbett has faced her own challenges throughout her career, some of which have predictably intensified since she became more of a public figure.

Kizzmekia, whose name is a combination of “Kizzy” from the character in Alex Haley’s Roots and “-mekia” from Brooks’s own imagination, has been teased since childhood and continues to be harassed about her name. When Kizzy showed her mother a particularly hurtful social media post, “I told her, tell them to call your mama,” Brooks recalls, “because your mama chose your name for a reason, because you’re a gift from God to me.”

As a child, even Kizzy’s strong interest in academic success was sometimes looked down upon by her peers, but “she just went beyond,” Brooks says.

Corbett has also experienced sexism and racism as a scientist. Brooks says sometimes men have skipped over Corbett and instead approached her boss, but “that’s why I like her boss, [Barney Graham] so much, because he’s always been behind her back,” she says—pointing people right back to Corbett.

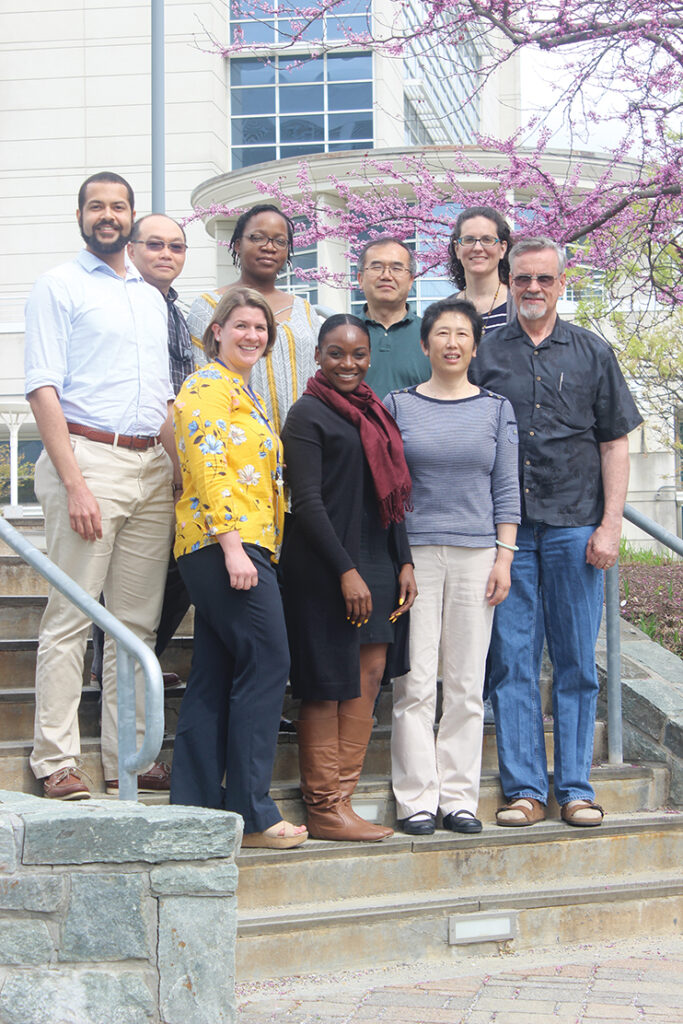

(Right: Corbett (center, front) with her NIAID research team, including Olubukola Abiona ’17, M25, biochemistry and molecular biology (center, back).)

Finding your champions

Corbett has taken her mother’s message to heart. “You just have to believe in yourself and believe in your work,” she says. Important, too, is having your own champions. “I always had someone in the space who was looking out for me,” she said—people like Sue Florence, Freeman Hrabowski, and Barney Graham. “Find those people and seek them out. You want someone to be as invested in you, as you are in you.”

High expectations and support from all those people who “got it,” cheering for her and setting the bar high from elementary school onward, combined with Corbett’s inner determination—and a dash of spunk—have fueled her success. If you had met a childhood Kizzy, she would have said, “Hi, I’m Kizzmekia Corbett, and I’m going to be the first Black woman to win the Nobel Prize in Medicine.”

Verbalizing one’s goals is a risk, because people will know if you fail. But it’s also a critical step toward turning them into reality. Little Kizzy knew it as a kid. “It speaks to putting yourself where you want to be, and really speaking the words to the universe,” she told Hrabowski. Even if she hasn’t reached her childhood goal yet, she’s happy with what she’s been able to accomplish so far.

“I haven’t won a Nobel prize, and I don’t know if I will,” she says, “but I think helping to ‘save the world,’ so to speak, is good enough.”

For now.

Read more about other ways Retrievers are giving their time and efforts to help others access the vaccine.

*****

Header image of Corbett on campus in April 2021 by Marlayna Demond ’11.

Tags: Biological Sciences, COVIDresearch, MeyerhoffScholars, mhoff, sociology, Spring 2021