Christina Ralls ’07, imaging and digital arts, recently completed a public art project that allowed her to dive into her family history and tell a story about one of the most turbulent moments in Baltimore’s recent history. UMBC Magazine asked her to share that experience:

Cold concrete blocks have replaced glass windows and front doors. An abandoned Catholic church casts its ominous afternoon silhouette on the abandoned intersection at Eager and Valley streets.

Many would say this sight is a familiar one in East Baltimore today, but this visit was different for me. It was my first day as community artist-in-residence for University of Baltimore’s Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth initiative. I was here to look into an ugly shadow of my family’s past.

This neighborhood was my mother’s home before the race riots of April 1968, when Baltimore’s city blocks exploded in anger and grief after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. During the uprisings, my mother’s family returned to find almost every belonging in their house – including cherished photographs – destroyed. The National Guard escorted them from their neighborhood. They did not return.

The Baltimore ’68: Riots and Rebirth initiative sought “to explore the causes and effects of the social unrest in Baltimore” in April 1968 and chronicle attempts at civic healing. The university told that story through various projects: an online archive, an oral history, a community-driven theatre production, a three-day public conference and an anthology of research papers.

My job was to bring community arts into that mix. Communal storytelling within a group of diverse individuals often results in a more encompassing and equitable documentation of that community’s shared history. Art is an effective and underutilized tool to tell those often-untold stories. Visual depictions of events can concretize memories and allow those who participate to better understand their past and its relation to the present.

I contacted approximately 60 participants in the initiative’s oral-history project and asked if they would be willing to create a mosaic about the events of April 1968. Our first workshop in January 2008 drew 12 people, including my own parents, who were both witnesses to the events of that year.

The attendees shared their experiences and perspectives about the riots, and how those events impacted their lives. Each story brought a unique perspective: A priest who led an Easter vigil while chaos ensued outside. A lawyer who defended curfew violators arrested for simply returning home after work. A present-day community activist who admitted to looting when she was a teenager. A former Baltimore Sun reporter who had recorded the turmoil in snapshots. A man who remembered living in a peaceful middle-class black neighborhood suddenly surrounded by the National Guard.

The openness and candor was astonishing. I was especially proud of my mother, who for the first time in her life shared a full account of her experience losing everything in the riots. The session concluded with everyone working in teams to create a paper mosaic about a relevant theme – and these dozen people who were strangers when they walked in seemed like friends at a 40-year reunion by the end of the day.

Moments of enlightenment continued as the process moved forward. When one participant described his experience with segregated hospitals, my father admitted his ignorance of race relations in that era. “I had no idea that hospitals refused patients based on the color of their skin; I always thought they were to treat everyone who needed help and care,” he said. “I understand now why anyone would riot if they were treated like that.”

Robert Birt, another participant, later told the Christian Science Monitor: “As I looked at the riots while they happened in my neighborhood, I knew the stores of white merchants were burned. But to be frank, after King was killed, I didn’t give a damn. That was my attitude. But when you hear the story of Christina’s mother – somebody’s family – come on. And she was my neighbor, too, I realized.”

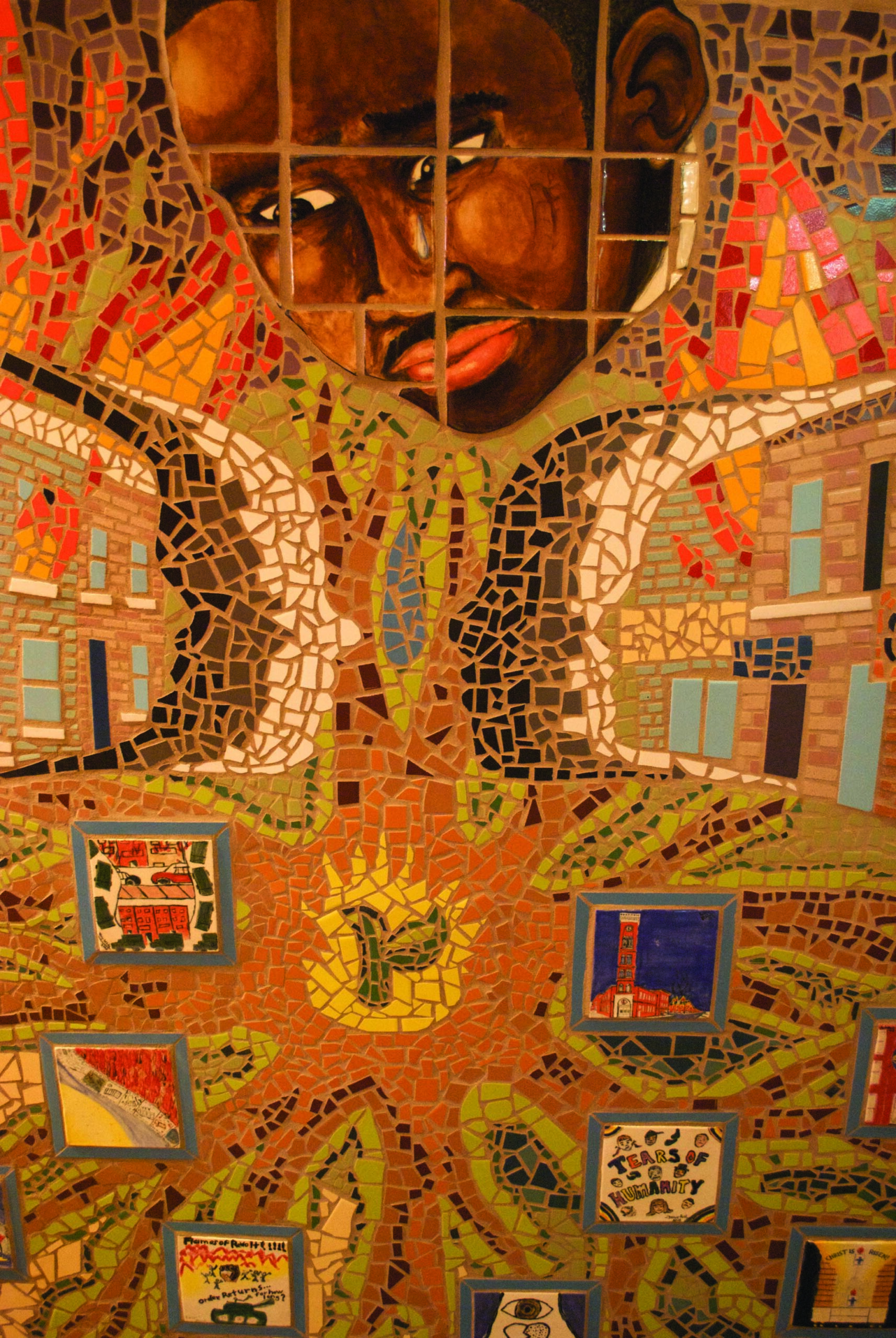

In the seven meetings that followed over a three-month period, a dedicated group of ten people continued to attend workshops. Together, we worked through issues of design aesthetic, critique, and storytelling, and plans for a large mosaic and individual 6” x 6” ceramic story tiles emerged. A growing sense of shared ownership also took hold. I gave them tools, but our collaboration went beyond anything I could have ever imagined.

In late spring of 2008, several of us worked tirelessly to create the final mosaic. We finished it in time for an unveiling at Baltimore’s annual Artscape festival in July. The overall assessment of the project was positive. Some members of the team believed that the mosaic brought them together as a community that was reminiscent of the Baltimore they remembered and loved – a place of respect and belonging.

The mosaic project was grueling and rewarding. But it allowed participants to claim ownership of their individual stories and collective history through art – and share what they had discovered with the wider community. In the intimacy of respectful interaction, we might accept and even embrace our differences and the tensions and arrive at a greater understanding and community with one another.

Tags: Fall 2009