EXPLORING THE BORDER

When human beings have to be at a certain place at a certain time, they have lots of handy aids to do so: alarm clocks and watches, maps and GPS systems.

Michelle Starz-Gaiano, an assistant professor of biology at UMBC, is fascinated by the question of how cells do the same thing.

“Cells leave on time and get to a destination on time during development,” she says. “They get to the right places almost all the time and they don’t get lost.”

What guides cells? One aspect of this question that researchers in Starz-Gaiano’s lab want to understand is how cells decide which particular ones in an organism will move and which will stay.

For instance, many cells must divide as a person develops from an egg to an embryo, to a human being. And as they divide, those cells must also reorganize themselves – and many of those cells migrate to different locations within an organism to fulfill their missions.

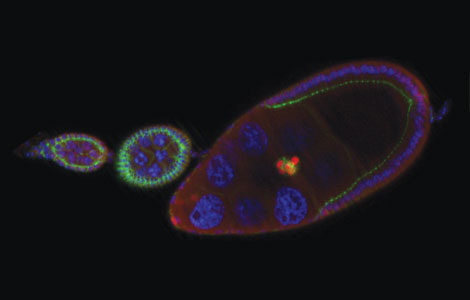

Starz-Gaiano and her colleagues are studying cell migration in fruit flies, concentrating specifically on a population of cells called “border cells.”

“Genes and proteins are similar between humans and flies,” Starz-Gaiano observes. “So if we can understand how they work in a simple system like flies, it really predicts how they’re going to act in humans.”

The relative simplicity of fruit flies also helps aid researchers. “In flies you can see how molecular changes translate to the whole organism,” she says.

How do Starz-Gaiano and her colleagues unlock the secrets of cell migration in flies? Biologists call it “loss of function” – but what it comes down to is simple subtraction and observation.

“We take away one gene at a time and see if the cells migrate or not,” she relates. “Then we can infer that those genes are required for cell migration.”

Studying cell migration is not just about exploring genetics. The observation of the border cells requires a great deal of live imaging with a microscope – which offers an enhanced look inside the process that is not available with a simpler two-dimensional observation.

“One surprise that came out of the live imaging is that [the migrating border cells] rotate,” says Starz-Gaiano. “People have done a tremendous amount of work looking at cell migration in tissue culture dishes where the cells are moving across two dimensions.” Live imaging offers the “huge advantage to look at the whole tissue at once.”

Interdisciplinary collaborations with the mathematics and chemistry departments, funded with help from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), have been a key to advancing the work being done in Starz-Gaiano’s research lab. (She is also the recipient of an NSF Early Career Award.)

The NSF’s Undergraduate Biology Mathematics Program has allowed Starz-Gaiano to team up with assistant professor of mathematics Bradford Peercy. “We’re doing some mathematical modeling to answer some of the harder questions about how the cells are moving and which cells are specified to move,” she observes.

Another grant from the NIH’s Chemistry Biology Interface Program (aimed to encourage interdisciplinary work by graduate students) is facilitating collaboration between Starz-Gaiano and UMBC professor of chemistry Katherine Seley-Radtke to explore applications that the cell migration research might have on drug design. Because cell movement is controlled in part by a cascade of molecules, this partnership is allowing researchers to work toward assembling drugs, molecule by molecule, that may inhibit some of the biological processes that promote cell migration.

— Nicole Ruediger

WIRELESS IS MORE

Most professors urge students to write concisely. But the students in Denise Meringolo’s public history class recently faced an extreme challenge to be succinct: Turn in a final project just 150 words long.

The work submitted by Meringolo’s students helped create a new smartphone app for Baltimore Heritage, a nonprofit preservation organization. The app leads users on a walking tour of Baltimore – and the 150 words is about as much text as can be read easily on an iPhone screen.

As an assistant professor of history and the coordinator of the public history track in the historical studies M.A. program, Meringolo often uses her Introduction to Public History class to collaborate with external partners on ways to enhance public understanding of history. Yet some of these classroom collaborations were never implemented by partner organizations, an outcome that was frustrating to a professor who likes to call her class: “Committing History in Public.”

Meringolo’s luck changed when she met Eli Pousson through UMBC’s Orser Center for Place, Community and Culture – where they are both board members. Pousson is the field officer for Baltimore Heritage, which needed content for their new “Explore Baltimore Heritage” app.

“It seemed like a very natural partnership,” says Pousson.

The collaboration on the app allowed UMBC students like Shae Adams ’13, M.A., historical studies, to wrestle with the issues faced each day by public historians. “I’ve had years of practice writing traditional research papers,” says Adams. “But to tease out a single story from that research and tell it in about 150 words? Much more challenging. Throughout the semester, I found myself loving the inherent challenge of interpretative public history.”

Meringolo’s partnership with Baltimore Heritage will continue this fall, when the graduate students in a class she’s called “West Side Stories” will create digital narratives – including oral histories – for the organization’s app.

Ironically, Meringolo doesn’t even own a smartphone yet. But she teaches her students that the principles of good storytelling stay the same no matter how the tale is conveyed.

“The mode of delivery is changing, not the impulse behind it,” says Meringolo, who has just published a new study of her discipline’s trends from the nineteenth century until today titled Museums, Monuments and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History (University of Massachusetts Press).

It’s no surprise that Meringolo sees her own work as part of that continuum, and she values the fact that UMBC is also becoming ever more engaged in the work of public history. “Public history is an intellectual discipline in the service of the community, and public universities are supposed to be in service to the world around them,” she says. “The more we can recognize that humanities scholarship is also a problem-solving toolbox, the more we can be relevant to the world around us.”

Meringolo has her sights set on 2016, when the National Council on Public History will hold its annual conference in Baltimore. UMBC’s partnership with Baltimore Heritage is one concrete example of what’s in the problem-solving toolbox of the humanities at the university. But the professor who likes “committing history in public” also hopes that it’s another step toward making UMBC a model of community collaboration by the time public historians arrive in Baltimore.

— Chelsea Haddaway

Tags: Fall 2012