Brian Souders ’09, Ph.D., language, literacy and culture, has directed UMBC’s Study Abroad program since 2000. His own travels and study have taken him to (among many locations) Finland and Russia, but Souders spent a week this past spring in one of the most secretive and closed-off nations in the world: North Korea.

Brian Souders ’09, Ph.D., language, literacy and culture, has directed UMBC’s Study Abroad program since 2000. His own travels and study have taken him to (among many locations) Finland and Russia, but Souders spent a week this past spring in one of the most secretive and closed-off nations in the world: North Korea.

Officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (or DPRK), North Korea hosts only a few thousand tourists annually – and only a fraction of that number are Americans.

A week spent in North Korea in March is not a spring break trip to Cancún by any stretch of the imagination. Most group tours do not start with a two-hour orientation that involves each individual signing a statement that they are not a journalist trying to sneak into the country. Nor do most group tours elsewhere in the world have a long list of rules and regulations – no photographs of soldiers, scenes of poverty, strategic buildings or anything that could remotely be construed as a military target or a source of embarrassment to the North Korean government.

In exchange for our agreement to these conditions? We were to be accompanied at all times by guides from the North Korean state travel agency. No long strolls on your own across Kim Il Sung Square in the capital city of Pyongyang. In fact, there was no time scheduled for any individual activity. Our assigned guides could get into serious trouble were we to wander off.

Time Traveling to North Korea

The best way to describe the week I spent in North Korea is “time travel.” A journey back to my very first visit to the then-Soviet Union in 1982. At the time, I was a high school exchange student spending my junior year in Finland – and our program included a weekend trip to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg).

As was the case in Leningrad in the latter days of the Cold War, Pyongyang is devoid of any commercial advertising. The city is full of propaganda in support of the Korean Workers’ Party (North Korea’s Communist Party) and the Korean People’s Army. The same lantern-jawed proletarians depicted in Soviet propaganda posters also appeared in Pyongyang with Asian – instead of European – features.

Even more ubiquitous were images of the three men who have ruled North Korea since its founding in 1948: the Great Leader and Eternal President, Kim Il Sung (1948-1994); his son, the Dear Leader Kim Jong Il (1994-2012); and his grandson, current leader, Kim Jong Un.

In the 1980s, the cult of personality among Soviet leaders had largely vanished, with only founder Vladimir Lenin’s portrait still widely displayed. The cult of the Kim family, however, is inescapable – disseminated via posters and portraits in libraries, schools, public squares, and in every single car of the Pyongyang metro.

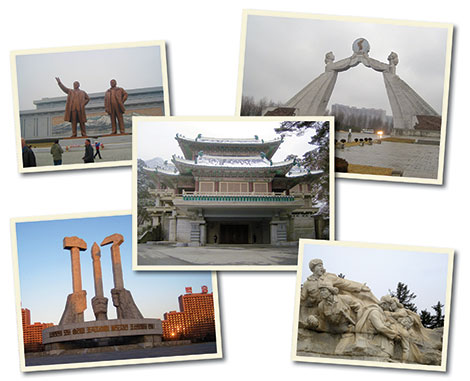

Our itinerary for the week also included visits to Mansu Hill (where statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il tower over the square) and Kumsusan Palace of the Sun (where both men are buried). We also paid a five-hour visit to the International Friendship Exhibition Hall, a museum with an endless maze of corridors connecting rooms filled with the more than 90,000 gifts given to the Great Leader and the Dear Leader by a long list of dead dictators – including the late presidents of Iraq, Libya, Romania, the Soviet Union.

“If you were to spend one minute looking at each gift in this museum to the Eternal President and his son, the Dear Leader,” our guide told us as the tour commenced, “you could spend a year here.”

We exchanged silent glances of panic.

A Chill in the Air

In March, the Korean Peninsula is swept by chilly winds from Siberia. But the contrast between South and North Korea in March is revealing.

When I visited South Korea in March 2012 to run the Seoul Marathon, I regularly had to open the windows in my overheated hotel room. But I rarely did so in North Korea – where hot water was sporadic, electricity intermittent (even in the capital) and indoor heating was not universal.

As our group headed into the Light Industry section of the Museum of the Three Revolutions during our trip, I had a bad feeling.

“Bundle up,” I told one of my fellow travelers. “We’re going inside.” We could see our own breath as we wandered from exhibition to exhibition.

I did catch a few memorable and unscripted glimpses of the country seen through the windows of our comfortable tour bus. The public face of Pyongyang glistened in comparison with empty, pothole-filled highways that wound past high-rise apartment rows marked by extreme poverty.

And I saw life beyond the city, too – glimpses of a stunning countryside where peasant farmers hacked through the snow-covered fields, following ox-powered plows in the bitter cold as they prepared for spring planting.

But was I able to experience the “real” North Korea? Our group never entered a regular shop or interacted with anyone other than roller-blading children at Kim Il Sung Stadium. We never touched (or even saw) North Korean currency.

The answer, sadly, is no.

Tags: Fall 2013