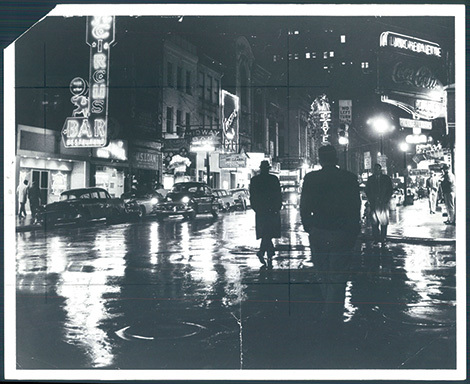

Mary Volkman ’92, English, is a Baltimore native who writes fiction under the pen name “Margo Christie.” Her first novel, These Days: A Tale of Nostalgia on Baltimore’s Block, relies not only on the author’s time working in show bars on the city’s most notorious stretch of real estate (right under the shadow of City Hall, hon) in the 1970s and ’80s, but also in her careful attention to the reminiscences of those who’d been there during the heyday of burlesque just after World War II.

But Margo Christie wrote the book. So let her tell it:

It’s often said first novels are autobiographical, inspired by the author’s coming-of-age and family of origin. Just as often, it’s said the best literature rises out of adversity. When I sat down to write a first novel, I was a step ahead of the game, having lived a tough life, and having not one, but two, families upon which to build my colorful characters. The first was, naturally, my family of origin – which included an alcoholic, disabled dad, nostalgic for his finer days; and a jazz musician grandfather, rumored to have played trumpet in “houses of ill repute.”

I fell into my second “family” when, at age 16, my first family broke up and (of necessity) I became a stripper on “the Block” – Baltimore’s once-stylish but by then seedy burlesque strip. My adopted Block family included burlesque-era strippers working as barmaids, and a strip-joint manager rumored to have consorted with the mob.

I fell into my second “family” when, at age 16, my first family broke up and (of necessity) I became a stripper on “the Block” – Baltimore’s once-stylish but by then seedy burlesque strip. My adopted Block family included burlesque-era strippers working as barmaids, and a strip-joint manager rumored to have consorted with the mob.

Milton Carter had been on the Block since the 1930s. During the heyday of burlesque, the 1940s and 1950s, Milton had been a “straw man” club owner, holding the liquor and cabaret licenses for the actual owners, mobbed-up guys who, owing to their criminal records, couldn’t get such licenses in their own names.

I met Milton when he was in his 70s and managing the Stage Door, a side-street joint housed within the rearmost portion of the historic Gayety Theater on Baltimore Street. Milton liked to tell the tale of the Stage Door in the old days, when it was “regular” bar where Gayety performers would relax between shows, drinking and carousing with their wealthy admirers, known as “Stage Door Johnnies.” Yet he was quick to also point out that no customer, regardless of how much he spent, had the right to assume anything about his Stage Door girls.

On my first day there, I was drinking with a guy who, having spent a considerable sum on champagne, thought that earned him the right to bully me into the back room. Milton intervened, pulling me aside to tell me I didn’t have to do anything I didn’t want to do. If I didn’t like how things were going with any customer, he said, I should tell the barmaid and she’d remedy the situation. This was important to know, as most Block clubs were fronts for prostitution in those days, and I was too green – just a month past 16 years old – to yet have a clear idea of what going in the back room really meant!

In this and other ways, Milton was like the father that my real father wasn’t, guiding me away from compromise and toward self-preservation. He regularly got on me about smoking cigarettes and advised me to stay away from certain dancers, those with drug habits and pimps for boyfriends. A health-conscious diabetic, he neither smoked nor drank. For his birthday and for Christmas, myself, the barmaid, and one or two other reliable day-shift girls, would chip in and buy him a big box of diabetic cookies.

Birthdays and Christmases were always celebrated at the Stage Door. The owner’s wife, a busty stripper who worked a “circuit,” like the burlesque queens of yesteryear, knew everyone’s birthday and never failed to provide a card and store-bought, personalized cake. On Christmas, the club was closed, but those of us without families showed up anyway. A cold-cut platter was spread across the bar, courtesy of the boss, and a gift exchange was organized by his wife. An overweight bartender who worked nights donned a Santa suit. A chair was placed onstage, names were drawn out of a hat, and every girl in attendance took her turn on Santa’s lap to receive a gift. Lacking in familial closeness as I was, rituals like this one kept me grounded, out of the path of drugs and pimps, as Milton often advised me to stay.

It’s unfortunate that in this modern age, American writers know so little of struggle. Not only have many of us never known it firsthand, but we live in a glib, image-obsessed world where sadness gets stuffed in favor of social media trends and “Likes.”

Studying English at UMBC in the early 1990s, I was fortunate to learn writing from Tom Nugent, a retired newspaperman who knew that to write about life one needed to immerse oneself in it. In the 1970s, he lived at Baltimore’s flea-bag Congress Hotel while writing an exposé about its welfare-roll inhabitants.

My advice for writers today? Live life on the edge, but with a safety net of “family,” real or adopted, to keep you on track when you drift into harm’s way.

Find out more about These Days and Margo Christie at her website: www.margochristienovelist.com

Photo by William H. Mortimer, October 22, 1973 – Baltimore Street also known as “The Block.”

Tags: Spring 2014