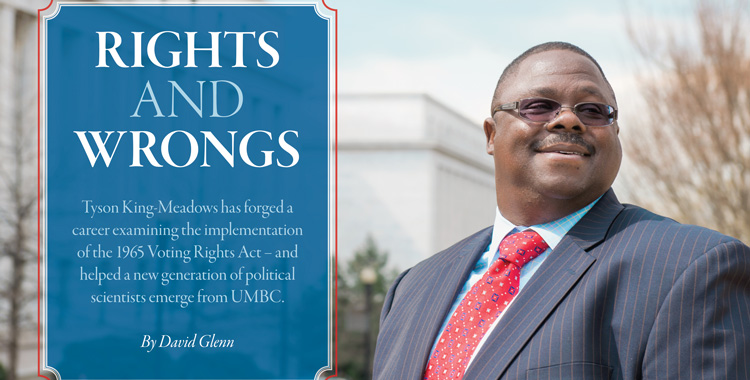

Tyson King-Meadows has forged a career examining the implementation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act – and helping a new generation of political scientists emerge from UMBC.

By David Glenn

Fifty years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act and seven years after the election of the first black president, what are the dynamics of African-American political participation? Can Southern states be trusted now to run fair elections without federal oversight? Can the Democratic Party sustain the coalitions that won the White House twice for Barack Obama?

Loose punditry on those topics is cheap and easy to find. But for empirically grounded analysis, scholars and policy experts are increasingly turning to Tyson D. King-Meadows, an associate professor of political science and chair of the department of Africana studies at UMBC.

King-Meadows has spent more than 20 years studying African-American political life, with an emphasis on the architecture and enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. When the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies – one of Washington’s most venerable African-American policy organizations – wanted to develop an analytic forecast of the black vote in various states in 2014, King-Meadows was one of the two experts they sought.

Such assignments have not turned King-Meadows into a creature of Washington, D.C. He first arrived at UMBC in 2002, not long after completing his doctorate in political science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a fellowship at Harvard University’s W.E.B. DuBois Institute for African and African-American Research. He also taught at Middle Tennessee State University and received a place in in the Fulbright Scholars Program, during which he traveled to West Africa, and taught and conducted research at the University of Ghana.

Since landing permanently at UMBC in 2004, King-Meadows has become a popular teacher and mentor at UMBC, and a campus leader on projects such as the creation of the minority postdoctoral fellowship program.

“Tyson is a strong scholar and a great teacher, but he also has this gift for administration and making things happen, which not many academics have,” says Tom Schaller, the chair of the political science department. Schaller first met King-Meadows in 1995, when both were graduate students at Chapel Hill. They also co-authored a book, Devolution and Black State Legislators, which published in 2006 by State University of New York Press.

“He seems to know everyone on campus on a first-name basis,” Schaller says.

Between The Lines

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) that King-Meadows has studied so closely is now approaching its fiftieth birthday. His research these days is turning much less to the history of the law itself, and to the huge range of dubious electoral practices that are not – and perhaps could never be – prohibited by federal law.

“Everybody knows about Julius Henson and the robocalls,” he says, referring to the 2010 case in which a Maryland campaign operative was prosecuted for deceptive phone calls that encouraged voters to stay home. “But there are practices out there that are subtler than that – for example, leaflets that say that you can’t vote if you’re behind on child support. The Supreme Court has sometimes argued that deceptive practices are freedom of speech, part and parcel of the practice of electoral politics. And maybe that’s correct. You really can’t legislate that kind of trickery away. What you have to have is a very aggressive or vibrant civic education strategy, so citizens reject those kinds of deceptions.”

That broad question of troubling electoral practices that are and are not covered by the VRA is the topic of one of two books King-Meadows is working on. The second book is a rhetorical analysis of how the how the Senate Judiciary Committee framed its discussions of race, representation, and democracy during the hearings which led to Sonia Sotomayor’s confirmation hearings to the Supreme Court.

King-Meadows is also co-editing a volume on African-American partisan identification, and supervising a team of undergraduate research assistants who are analyzing 55 years’ worth of U.S. newspaper coverage of voting rights, all in addition to directing UMBC’s Africana studies department.

“Tyson is incredibly thoughtful as a scholar, and I’ve also gotten to see him act as an institution-builder,” says Andra Gillespie, an associate professor of political science at Emory University, who was King-Meadows’ co-author on the 2014 analysis of African-American voting patterns. “When he served as president of the National Conference of Black Political Scientists, he encouraged us to be ambitious about where we could go as an organization. He’s a great colleague and a great friend. I feel lucky to have him in my circle.”

A Diverse Discourse

When King-Meadows started at North Carolina Central University in Durham, he expected to go to law school. Instead, he fell in love with political science, applying to graduate school a few miles away in Chapel Hill.

It was here that King-Meadows’ habit of multitasking took root. In addition to the eternal grad student burdens of studying and teaching, he plunged into several activist campaigns calling on UNC to do better at recruiting and retaining students and faculty of color.

“I realized that many of our concerns about the university’s commitment to diversity and inclusion were also related to curriculum,” he recalls. “Whose voices get into the syllabus, whose perspectives get elevated or excluded, and whose ideas get taken as empirical facts.”

Schaller joined King-Meadows in a few of those campaigns. “One of the formative early moments in our friendship,” he recalls, “was when he asked me, ‘How many times have you been stopped going into the building?,’ meaning Hamilton Hall, where the political science department is. And I said, ‘What? I’ve never been stopped.’ I always came in and out of the building late at night – that’s just part of the grad student life. You’re in your carrel reading or grading papers. No one ever questioned whether I was legitimately in the building. But every few months somebody would say to Tyson, ‘Excuse me, do you have any ID?’”

One of King-Meadows’ mentors at Chapel Hill was Terry Sullivan, a political scientist who is known for empirical studies of Congressional decision-making. (“Terry is where I got my love for Congress,” King-Meadows says.) Sullivan recalls that in King-Meadows’ first years of graduate school, he was besieged by appeals for support and advice from undergraduate students, especially students of color.

“He was drowning in these requests,” says Sullivan. “And that was hard on him as a graduate student, because he was trying to balance his obligations. But he took that burden, which was substantial, and turned it into something special. He used it as an opportunity to think hard about what he wanted to be as a teacher. By the time he left Chapel Hill, he was an award-winning instructor.”

Finding The Patterns

Shawn Tang ’15 is not surprised to learn that King-Meadows won a teaching prize back in graduate school. “I took a course on Congress with him last semester,” Tang says. “It was a conversation more than a lecture. You couldn’t get away with not doing the reading. He kept all of his students accountable.”

Shawn Tang ’15 is not surprised to learn that King-Meadows won a teaching prize back in graduate school. “I took a course on Congress with him last semester,” Tang says. “It was a conversation more than a lecture. You couldn’t get away with not doing the reading. He kept all of his students accountable.”

Today, Tang is part of King-Meadows’ small army of research assistants. Among other projects, Tang is analyzing and coding archival newspaper articles on voting rights in general and the Voting Rights Act in particular.

Another member of the team, Divya Prasad ‘16, says that King-Meadows gives his research assistants a generous degree of freedom, but also expects them to be able to defend their choices. “Whenever we do something in our research,” Prasad says, “he wants to make sure that we’ve really thought about how we’ve come to our decisions.”

Another member of the team, Divya Prasad ‘16, says that King-Meadows gives his research assistants a generous degree of freedom, but also expects them to be able to defend their choices. “Whenever we do something in our research,” Prasad says, “he wants to make sure that we’ve really thought about how we’ve come to our decisions.”

Lauren Lochocki ’14, political science was hired as an analyst at IMPAQ International after serving on King-Meadows’ team of research assistants. The duo have given papers together at academic conferences, and their collaboration was spotlighted as an example of outstanding undergraduate research by the American Political Science Association.

Lochocki says that “when I was applying for jobs, I was confident in the skill sets [I had], and I am able to apply them to where I’m working now.”

Coding newspaper articles is inescapably tedious work, but the experience may pay dividends. Rhoanne Esteban ’11, political science, worked as a research assistant for King-Meadows several years ago, analyzing data from surveys of African-American state legislators and voters in a racially divided Congressional district in Tennessee. She is now a doctoral student in political science at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

“When I started here,” she says, “I don’t think anyone else in my cohort had the range of research skills that I had. Dr. King-Meadows made sure that all of his RAs knew our methods. He always reminded us that other scholars have to be able to replicate our work.”

The newspaper-coding project will inform King-Meadows’ book-in-progress on deceptive election practices and congressional authority to stop them – a sequel to his earlier work When the Letter Betrays the Spirit (Lexington Books, 2011). In that book, King-Meadows argued that throughout the Voting Rights Act’s history, Congress has been too passive in overseeing the law’s enforcement, and too willing to defer to the preferences of the executive branch.

That passivity, King-Meadows believes, was baked into the law from the beginning: When Congressional members were crafting the bill in the spring and summer of 1965, Lyndon Johnson successfully pushed for language that gave enforcement discretion to the Department of Justice.

That impulse was understandable – the White House didn’t want to cope with obstruction from recalcitrant Southern senators. But the flexibility carried a heavy cost, King-Meadows believes. Because the VRA has given extensive discretion to the executive branch, certain presidents have chosen to enforce the law only weakly. If Congress had written the law more tightly, King-Meadows believes, it would have been less subject to watering down by the executive or by the courts.

“You have the same law that can be enforced strongly or weakly depending on the preferences of the executive branch,” King-Meadows says. “And the various coalitions in Congress have never really figured out how they want to respond to this.”

After completing his 2011 book, King-Meadows got to see that confusion and ambivalence up close. He won an American Political Science Association Congressional Fellowship, a program that embeds academics in the Capitol. He spent a year as a staffer on the House Judiciary Committee, which was then led by Chairman Robert Goodlatte, a Republican from Virginia, and ranking member John Conyers, who is a Democrat from Michigan.

“This was absolutely the greatest experience of my professional life,” he says. “I got to be in the room, to see documents, to attend strategy sessions, to write memos. I got to walk to the Supreme Court for the oral arguments in Shelby County v. Holder.” (In that 2013 case, the court voided a key component of the Voting Rights Act.)

“That year has absolutely changed the way I teach Congress and the way I mentor students,” says King-Meadows. Among other things, he was struck by the influence wielded by fresh-out-of-college legislative staffers.

“A lot of political science students think they have to go to law school and do this and that and wait years until they can change the world,” King-Meadows says. “And I try to explain to them: No. If you pick up the right skills as an undergraduate, you can go out and change the world right now.”

Tags: spring 2015