AFTER YEARS IN DEVELOPMENT, AND MONTHS OF WAITING, A UMBC-DEVELOPED MINI SATELLITE LAUNCHED INTO SPACE STUDIES CLIMATE AND AIR QUALITY, PROVING PERSISTENCE PAYS OFF.

In the early morning hours of Saturday, November 2, 2019, a few hundred guests at the NASA Wallops Flight Facility gathered at the VIP launch viewing site—a grassy pad near a large tent. Sitting on metal bleachers and in camping chairs, they gazed upward. The NASA Antares rocket and the Northrop Grumman Cygnus capsule stared back at them from two miles away, more than 14 stories high and loaded with supplies for the International Space Station (ISS). Also on board were more than 30 “cubesats”—small satellites no bigger than large loaves of bread—all of them containing scientific instruments their makers hoped would contribute to a better understanding of our world.

One cubesat, the Hyper-Angular Rainbow Polarimeter (HARP), has been a labor of love for a small group of dedicated UMBC scientists and engineers for the last five years. There were times when they weren’t sure if HARP would ever get to space, but the big moment had finally arrived. Today, HARP was headed up. Way up.

Around 9:55 a.m., the crowd quieted. Their thoughtful silence spoke to years of late nights, early mornings, sighs and tears, hugs and high-fives. They thought back to team meetings with frantic napkin scribbling, spacecraft models made of children’s toys when an idea struck at home, and big dreams.

UMBC’s Roberto Borda, one of the core engineers for HARP, stood at the front of the viewing area, his arms around his wife. “It’s happening, it’s happening!” he whispered excitedly in her ear. Other team members stood nearby with their spouses, children, and friends.

The crowd collectively held its breath and squinted across open fields at the rocket, which was backed almost directly by the low morning sun. And then, finally, it got loud. Really loud. The silent guests watched as Antares and Cygnus roared to life, 440,000 pounds of oxygen fueling eight massive explosions generating upwards of a million pounds of thrust.

At exactly 9:59:37, right on schedule, the rocket burst from its restraints and bolted upward into the sky. Cheers erupted, and the nervous tension dissipated as the rocket rose ever higher. Within four minutes, it was 100 miles above the Earth, headed to the space station at 17,000 miles per hour.

A few minutes later, champagne bottles popped and the celebration began.

Observing particles in Earth’s atmosphere

The HARP satellite’s unique sensors will collect new kinds of information about clouds and tiny particles in Earth’s atmosphere, such as wildfire smoke, desert dust, and human-generated pollutants. These particles, collectively known as aerosols, have a multitude of effects on the global climate and the health of organisms. For example, rain droplets condense around the particles, so they play a role in global precipitation. The particles can also reflect light away from Earth as well as trap energy inside Earth’s atmosphere, which both affect climate. And pollutants can lead to various respiratory ailments in humans and other animals.

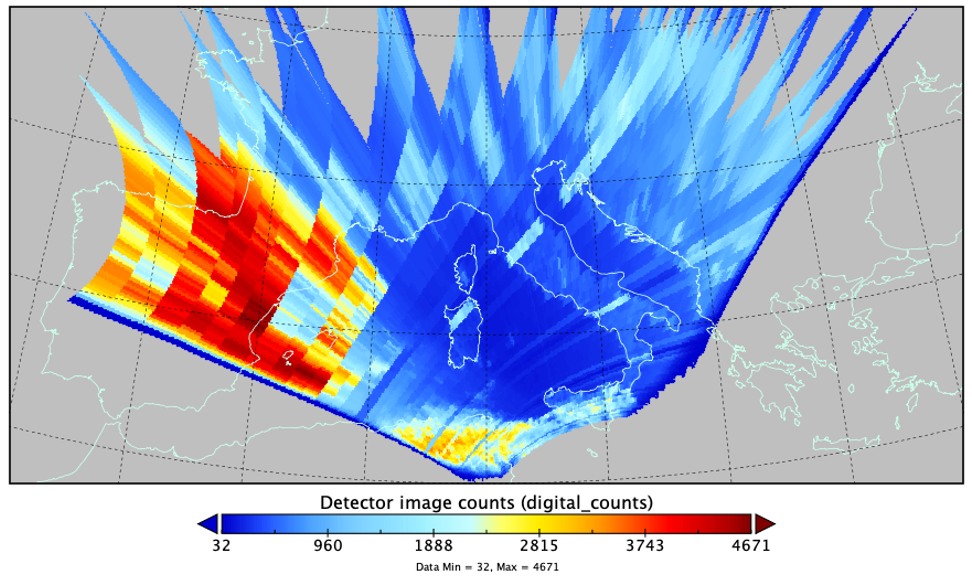

With its innovative design, HARP is able to observe the particles from many angles at once to give scientists a more comprehensive view of what’s going on in the atmosphere. The new data will equip scientists with information they need to better understand climate and air quality concerns.

“HARP is really a technology demonstration mission,” explains Vanderlei Martins, the lead researcher on HARP and director of UMBC’s Earth and Space Institute, “but our goal is to also do some science with the data.”

The team includes engineers, physicists, and mathematicians from UMBC and Space Dynamics Laboratory (SDL) in Utah—which designed the exterior parts of the satellite that would carry the UMBC instrument into space. “As an engineer, I’m looking to develop technology that can make the science happen,” says Dominik Cieslak, an assistant research scientist with the Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology (JCET), a UMBC partnership with NASA.

Other UMBC team members are developing algorithms to effectively analyze the data that will eventually be arriving in huge quantities. Cieslak notes that the data could be used in new ways for years to come as researchers develop new algorithms and computing power continues to grow.

Awaiting “first light”

“We’re going to celebrate every step,” Martins said on the morning of the rocket launch. He was careful to note that the launch was just one step—a particularly exciting one—in a lengthy sequence. Only when the satellite was safely orbiting Earth and sending back data would he and his team know whether HARP was working the way they intended.

Despite the additional steps to come, the launch was “a big milestone,” said Brent McBride ’14, physics, a current Ph.D. student in atmospheric physics. With the setbacks the project had experienced over five years, to arrive at launch day was “a wonderful thing.”

Cieslak acknowledged that going forward, “there are many ways for things to go wrong—but there is only one way for everything to go right.”

To increase the likelihood of things going right, before the rocket launch the team tested HARP many times on two different kinds of aircraft that fly at high and low altitudes, to ensure the instrument was working properly. But still, says Borda, “It’s a different beast going in a plane versus going to space.”

If every step in HARP’s journey went perfectly, it would be sending back images from space—the first of which the team calls “first light”—within a few months. “I’ll really, really celebrate when we get the first light,” Martins said.

A hero’s journey

Two days after it launched from Wallops, on Monday, November 4, the Cygnus capsule made it safely to the ISS—another step completed. Then, the team waited with anticipation until astronauts were available to release it into orbit. Finally, after multiple delays, on February 19, 2020, UMBC community members gathered in the Physics Building to watch a live stream of the release.

“We are 55 seconds from jettison,” came the voice over the internet. Once again, the crowd fell silent as the clock ticked down. At the prescribed moment, the group witnessed a small blob silently exit the launch tube and float slowly into space. HARP was the 100th cubesat ever launched by NASA. The successful ISS release was another necessary step—if less dramatic than the rocket launch—along HARP’s journey.

Then, more waiting. Even if HARP was collecting data, if it couldn’t send that data back to scientists on Earth, all would have been for naught. Thankfully, a little over a week after HARP’s release, Earth-bound instrumentation at Wallops successfully established a connection with the satellite.

Still, the team didn’t know then if HARP was actually working. Under normal circumstances, the team would have gotten an answer to that question within a few more weeks, by mid-March. But that was just as COVID-19 began to wreak widespread havoc in the United States. So, more waiting for the HARP team. NASA, UMBC, and Space Dynamics Laboratory employees scrambled to figure out how to operate the satellite from their homes, and competition for data transfer time on ground-based instruments became ever steeper, as NASA’s capacity dwindled.

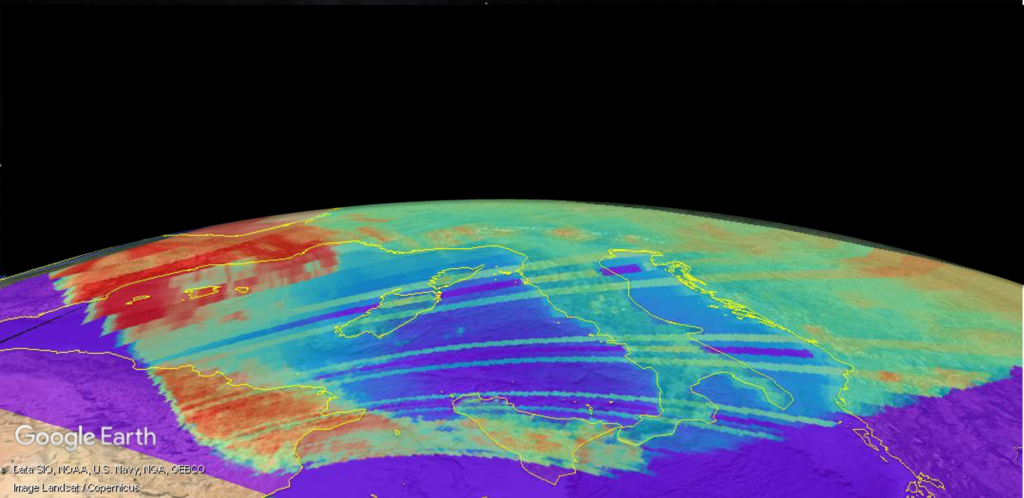

Finally, on April 15, 2020, a full nine weeks after HARP’s release from the ISS, almost six months after its launch on the Antares rocket, and nine months since anyone on the HARP team had actually laid hands on the instrument—not to mention the years and years of research, design, and construction of HARP itself—it came. First light. And it was perfect.

Moment of Truth

A week later, Martins perused the first fully-processed image, which happened to be of the Mediterranean region. The outline of Italy was clearly visible. He started out as any scientist would, making careful, objective observations: “There are no defects. So far, there are zero issues with the UMBC payload. It is working as designed, and so far, it has exactly the same performance as we had in the lab.”

Slowly, it started to sink in. Every setback, every time he and his team had put off celebrating, every time he had tempered his enthusiasm in anticipation of first light… Well, here it was. First light. Then, it came out in a rush:

“You know, the last time we touched the sensor was last September. It has been shipped, it has been transported, it was launched in a rocket to the space station, it was released from the space station…All those things happened and we had no idea how people were treating it… is it contaminated? Is it broken? And so far… everything is perfect.” His smile grew broader.

“Now, it is operating in space. HARP is a demonstration of a new technology that was completely developed at UMBC, and it is now operating in space. It’s working, it’s performing, it’s showing everything we expected and that we’ve been working toward for the last 10 years…So it’s fantastic.”

True Teamwork

Karl Steiner, UMBC’s vice president for research, was thrilled to witness his first NASA rocket launch as HARP leapt into the sky on November 2. “To have seen Vanderlei and his team work on this as long as I’ve known them, and know the amount of work and sacrifice they’ve put in, the chance to be with them on this important day…” He trailed off, brimming with emotion. “It’s a very special day for the team and for UMBC.”

Steiner’s pride only grew as HARP continued its journey. “This successful launch of the HARP CubeSat is the latest achievement in a long string of impactful scientific and technical milestones from UMBC and its Earth and Space Institute,” he shared. “We can’t wait to explore the scientific data that HARP will make accessible.”

No team deserves this success more than Martins’. After every setback, they never gave up. Even when the instrument was damaged during testing, Cieslak brought it back to UMBC from Space Dynamics Laboratory in Utah, completely deconstructed it, cleaned it, and put it back together. “It turned out that after that operation, the instrument was working better than before,” Martins said. “To me, that’s a testament to my team.” Always rising to the occasion. Always coming back stronger.

Persistence pays off

Yet, even after achieving first light, and proving that this technology—which is unlike any ever deployed in space—can work, the team isn’t resting on its laurels. HARP2 is well underway, and is scheduled for launch on NASA’s PACE mission in 2021. HARP2 will have bigger scientific goals, and even better optical, electrical, and mechanical systems.

Much of HARP2’s infrastructure is being designed by UMBC students, who have dubbed themselves “the space coders.” The HARP2 team includes three Ph.D. students, one master’s student, and eight undergraduate students—seven from UMBC and one from Towson University. The HARP team also included two high school students.

All this looking forward provides powerful motivation for a dedicated team. But looking back is important, too. At a pizza party after the rocket launch, the team members reminisced about the time they’ve spent together—some as many as 15 years on other projects and five years on HARP.

“Life can surprise you. Even five years ago I couldn’t have imagined I’d be here today. So keep dreaming,” said Cieslak. “Keep dreaming.”

******

Header image designed by Dusten Wolff ’13.

Tags: CNMS, Spring 2020