UMBC’s Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars Program has launched an intensive virtual math incubator for Lakeland Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore City this summer. The free, voluntary five-week program is a math intervention for 150 Lakeland students in third through eighth grade. The program seeks to prevent summer learning loss, which could increase this year, intensified by COVID-19’s impact on student learning during the school year.

“With the changes this spring to learning, the UMBC/Lakeland Summer Math Program has allowed us to make up ground and get a head start with students in a targeted approach to math instruction,” says Lakeland Principal Najib Jammal. “This partnership lets us plan for students’ needs this fall knowing that 150 of our students had access to high-quality math instruction the summer.”

Jammal recently spoke about the collaboration in an interview for the segment “Staving Off Summer Slide” on WYPR’s On The Record.

The summer program was designed to also have a lasting impact beyond improving specific STEM skills. Lakeland teachers and UMBC partners are helping Lakeland students develop a positive math identity that will carry them forward into higher level math courses.

Moving online

The summer STEM program was originally designed to be held in person. COVID-19 both increased the need for the program and required Lakeland to move instruction online, decreasing student–teacher and peer interactions. To counter this challenge, program organizers knew they’d need more teachers to decrease the student–teacher ratio and reach more students overall.

The Goldseker Foundation and Baltimore Children’s Youth Fund (BCYF) provided the funding needed to implement the program online and to hire more teachers. Their financial support also expanded the program from the initial 60 rising fourth through sixth graders to 150 rising third through eighth-grade students.

This creative intervention has three priorities: whole child development, math identity development, and math growth. The program is implemented under the direction of Josh Michael ‘10, political science and education, assistant director of UMBC’s Sherman STEM Teachers Scholars Program, in collaboration with five Baltimore City school teachers and twelve interns from the Sherman Scholars program.

Whole child development

UMBC has fostered a strong partnership with Lakeland for more than five years. It has supported Lakeland’s wrap-around academic and community services through the Sherman STEM Teachers Scholars Program, the Sherman Center for Early Learning in Urban Communities, and the Shriver Center Literacy Fellows program. Through additional collaboration with area community groups and companies, such as Northrop Grumman, Lakeland has built a safe and supportive community where students can thrive socially and academically.

The summer program also relies on a firm foundation of strong teacher, student, family, and community relationships. The Sherman STEM Teacher Scholars serve as program leaders. In this role, they dedicate the majority of their day to fostering relationships with students and their families through video chats, phone calls, texts, and emails.

These program leaders coach the three Lakeland teachers who serve as program facilitators, including one UMBC alumna. Former Sherman Scholar Molly Hart, M.A.T. ‘19, elementary education, is now a sixth grade math teacher at Lakeland and serves as a facilitator for the summer STEM program.

“The program’s support system is incredible,” shares Haleemat Adekoya ‘23, political science. She says this experience has made her aware of the importance of consistent communication in the classroom.

If a student is absent one day, her priority is to get in touch with their family as soon as possible. “Every time I let a student and their family know they were missed, as an intricate part of the classroom community, they’ve shown up the next day and actively engaged.”

This structure of robust support is cultivating strong student and family relationships and student participation. Out of 150 enrolled students, an average of 120 consistently engage in math instruction and STEM activities each day. Nearly 100 percent engage each week. Once students feel supported and are engaged, teachers can then move forward to focus on further developing students’ math identity and math skills.

Math identity

Historically many Black, Latinx, and first-generation students, as well as English Language Learners (ELL) and students experiencing economic hardship, have faced obstacles in math achievement. Limited public school resources, insufficient access to quality culturally relevant instruction, and high social/emotional stresses have created learning gaps at lower grades, which often deepen in upper grades.

For many students, negative experiences in trying to build fundamental math skills have impeded their development of a positive math identity. Math identity is a student’s perception of their ability to perform well in math. It has been shown to impact math performance.

These factors have also contributed to a lack of diversity in STEM fields, reinforcing the negative stereotype that underrepresented students can’t do math regardless of the resources available to them. As a result, underrepresented students are less likely to feel confident enough to pursue higher level math courses. This further limits their access to a variety of academic, career, and social opportunities.

“I am terrified of math even though I was given all the support and resources to excel in math,” explains Adekoya. “Josh Michael and Lydia Coley give me the support and confidence to lean into this opportunity and not give in to imposter syndrome. I have to lead by example.”

Lydia Coley ’20, American studies, valedictorian of UMBC’s most recent graduating class, is also a program leader and a Sherman Scholar alumna. She is a first-year, sixth grade math teacher at Maree G. Farring Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore City.

Me, myself, and math

Lakeland serves 1,000 Pre-K to eighth-grade students. The majority come from underrepresented populations in STEM fields. They are less likely to have a positive math identity. Black students make up 32 percent of the school, 62 percent are Latinx, 42 percent are English Language Learners, 11 percent receive special education services, and most students come from low-income families.

The summer program aims to help Lakeland students break the cycle of underrepresentation. Immersing students in a safe and nurturing space encourages them to engage in the math learning process. It also broadens and strengthens their math skills and fosters a positive math identity.

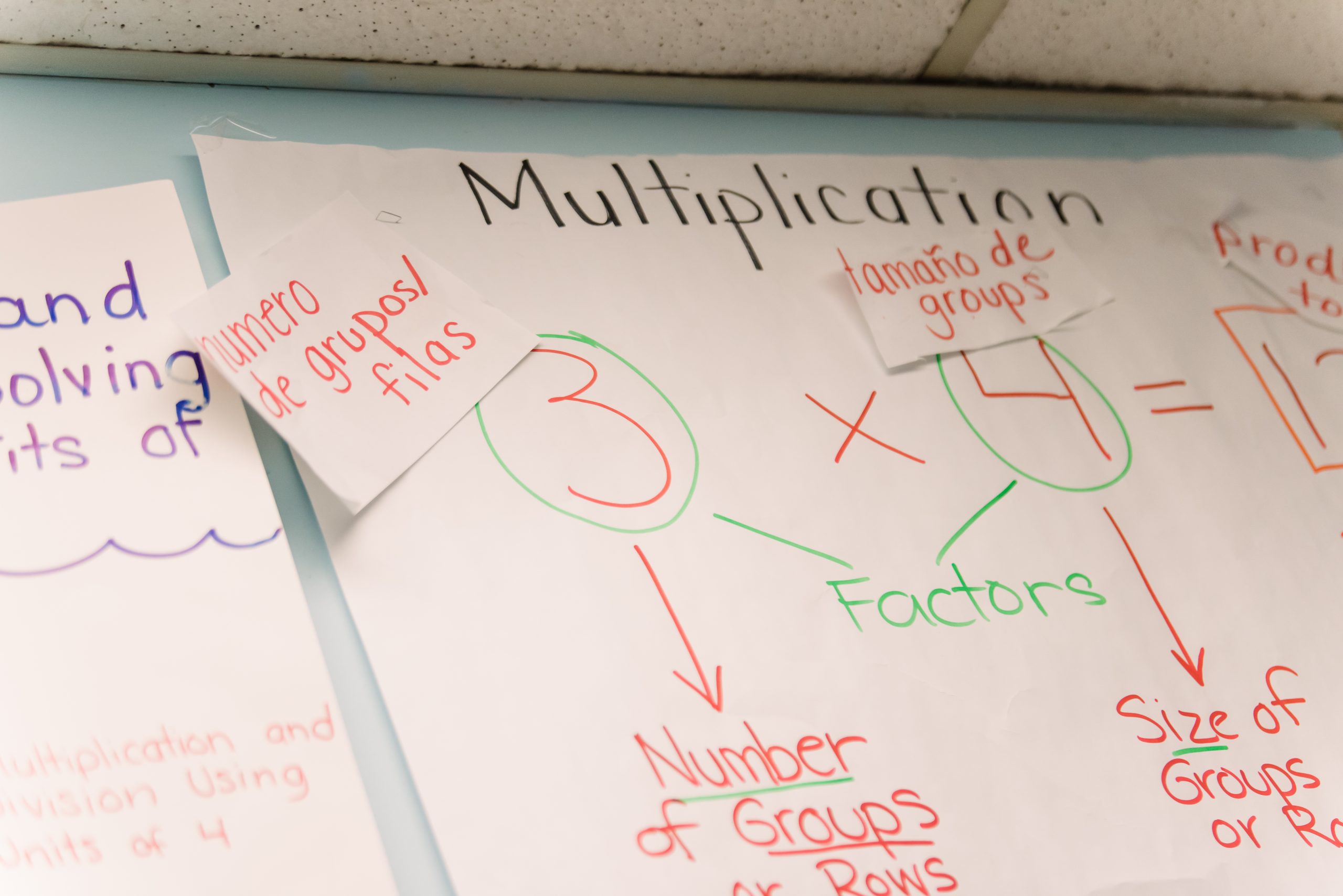

Through daily interactive synchronous video lessons, based on common core standards, program leaders teach, model, and provide individualized instruction. Students develop a toolkit of strategies that build the confidence needed to take risks and see mistakes as learning opportunities.

Program facilitator Iliana Hernandez, a fifth-year, third grade math and dual-language teacher at Lakeland, provides program leaders with best practices to support ELL learners. She admits her own fears of math in elementary school. “I don’t want my students to fear math like I did,” shares Hernandez. “When students stay connected and feel valued and cared for their confidence grows and they feel ready to learn.”

Math growth

With this foundation in place, rigorous math instruction can move forward. Program Director Carly Harkins leads the team in curriculum development and instruction. Under her guidance, program facilitators coach program leaders in weekly lesson planning, lesson delivery, assessments, and student support. After daily class, students practice independently through proven online learning tools wherever they are on their math journey.

The program also provides hands-on experience to help students apply what they are learning. Josh Massey, the STEM facilitator, works with Michael and Harkins to create hands-on STEM activities for students.

Massey ‘18, computer engineering, and M.A.T. ‘19, technology education, is a first-year computer science teacher at the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute in Baltimore City. He creates 150 STEM kits weekly, and helps deliver them to students’ homes. Each kit includes the materials needed to complete a project. They tie into the week’s topic, like circuits or small machines.

Students first work on the project independently and then share their process in class. Each student is then the proud owner of something they have built themselves. These projects help support both math growth and a positive math identity.

Access to a bright future

When Michael sees students participating in these activities, he sees them as accessing the building blocks they’ll use to excel in the years ahead.

UMBC and Lakeland partners hope this extra support will ensure more Lakeland students will be better prepared for Algebra I when they enter eighth grade. Why? “Algebra I is a key academic gateway,” says Michael. “There is strong evidence that successfully completing Algebra I in eighth grade is related to higher math achievement in high school and attainment in college.”

Michael notes that it’s long been the case that students of color have had less access to Algebra I in eighth grade. He shares, “Our goal is to provide that access by helping students believe success in math is for them.”

Banner image: A math chart in Coley’s classroom during her student teaching internship. All images by Marlayna Demond ’11 unless otherwise noted.

Tags: AmericanStudies, CAHSS, COEIT, Education, History, PoliticalScience, Resilience, ShermanScholars