Bats as biomonitors, community connections to the zero-waste movement, and oyster aquaculture are just a few of the topics that students in UMBC’s Interdisciplinary Consortium for Applied Research in the Environment (ICARE) master’s program are exploring through Baltimore-centered community-engaged research. As the first cohort in the program heads into their second and final year, they are excited about their work and looking ahead to becoming the next generation of environmental science leaders.

“B” is for bat

Chris Blume, M.S. ’23, geography and environmental systems, has studied bobcats, bees, and birds. So when he came to ICARE, he jokes, “I had to choose another ‘b’ animal.” Jokes aside, in his undergraduate and working experience, Blume found that “the social aspect was missing” in conservation science, which often focused on wildlife. “And that’s what drew me to ICARE, because it seemed like there was a focus on the community.”

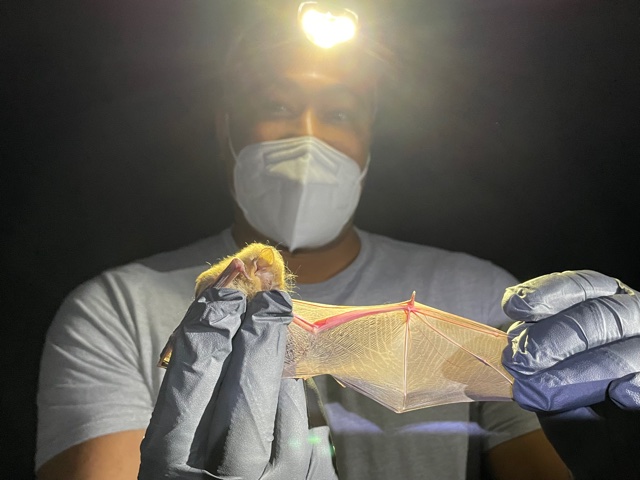

In his project, Blume is using bats as biomonitors to detect levels of heavy metals in different neighborhoods across Baltimore. “Because of their biology and their ecology, they make great biomonitors in rural environments,” he says, “but I wanted to see how that works in urban places.”

How can bats provide information about heavy metals? Through their guano (poop). “I have literally a fridge with a bunch of guano,” he says, waiting for analysis later this fall. In addition to the guano analysis, Blume is giving away bat boxes to local residents and offering evening “bat walks” to teach local Baltimoreans about these important native critters. He’s also created citizen science opportunities by posting acoustic recordings of bat calls on a public website, where anyone can listen and help identify which bat species show up where.

In the future, Blume wants to pursue a Ph.D. and continue his bat research, as well as continue to create citizen science and community engagement opportunities.

Building the bridge

Natalia Figueredo, M.S. ’23, geography and environmental systems, has always been community-oriented, influenced by her early childhood in Bolivia and her teenage years in Queens, New York. In New York, she noticed that “there were all these big projects going on in communities, and the community didn’t ask for them,” she says. She wanted to do something different.

After working with the Ironbound Community Corporation in Ironbound, New Jersey, she became passionate about doing inclusive research for mutual benefit, and ICARE was a perfect fit to advance her career. “What interested me about this program,” she says, “is that it was trying to build that bridge between scientific research and community engagement.”

Figueredo’s research project focuses on engaging South Baltimore residents in the zero-waste movement, in the context of recent battles over a nearby trash incinerator. She is also working closely with partners at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) and the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, in addition to her faculty mentor Maggie Holland, associate professor of geography and environmental systems.

Figueredo is surveying residents from across the city about their waste management practices and access to the zero-waste movement. She’s also interviewing South Baltimore community leaders and conducting focus groups with neighborhood residents. Figueredo hopes to find out whether they feel supported in pursuing zero-waste goals and to learn what local knowledge and practices already exist related to the movement—whether or not the residents identify them as such.

Research always comes with bumps in the road, but overall Figueredo has had a rewarding experience so far. She wanted to choose a graduate program where people would champion and support her, she says—“and that’s definitely how I feel with the ICARE team.”

Putting research into practice

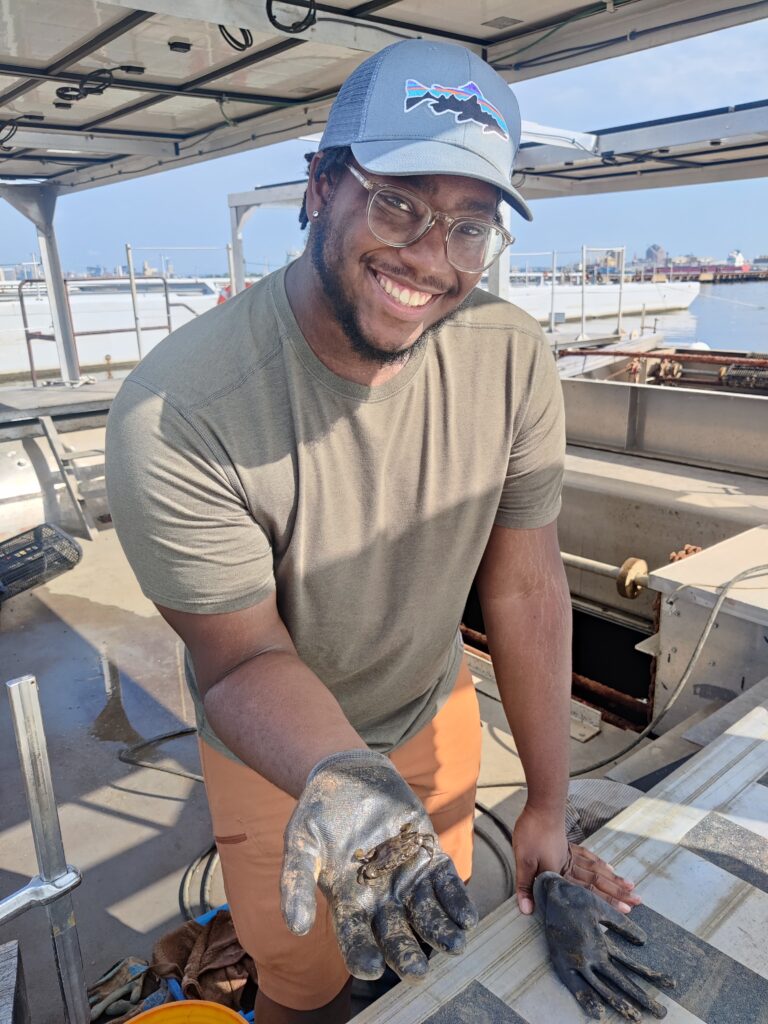

Darryl Acker-Carter, M.S. ’23, marine, estuarine, and environmental science, is studying a new method of oyster aquaculture with partners at the company Solar Oysters. Traditionally, oysters have been cultivated in wire baskets at the water’s surface. A new system, called the Solar Oyster Production System (SOPS), uses a solar-powered ladder structure to rotate the baskets through the entire water column. The goal is to produce healthier, more-uniform oysters in less space. At the end of the growing season this fall, Acker-Carter will compare oyster size, survival rate, and meat-to-shell ratio of oysters in the experimental rotating ladders, non-rotating ladders, and traditional surface-only baskets at a site in Curtis Bay, in south Baltimore.

Acker-Carter has been interested in oysters for several years. “I like social science, but I also like the biological side of things, and I saw that nexus through oysters,” he says. To some, how to best cultivate oysters may seem like a purely scientific question, but “when you actually get down to, ‘Let’s make some change,’ it’s all social science,” Acker-Carter says, “because it’s all managing people and their perspective about how to harvest oysters and their relationships to natural resources.”

The ICARE program has helped Acker-Carter see how research fits into community engagement. “I used to think research was very isolated,” he says, “but in ICARE, you’re putting that research into practice. You can create benefit in the community by doing the research, and giving people access to that data.”

Committed to community

For program leader Tamra Mendelson, professor of biological sciences, ICARE is exceeding expectations. “I am thrilled with how the program is going,” she says. “The students themselves are so strong. They are motivated. They are engaged. They are very sharp, and they’ve bonded as a cohort, which makes us really happy. I do think that’s a huge secret to success—having students feel like they are part of a network of peers supporting each other.”

The community partners have also been critical for the program’s success. One session led by Stephen Freeland, director of the individualized study program at UMBC, brought students and partners together for a brainstorming session across projects and topic areas, embodying the program’s commitment to bridging science and community. “Just bringing everyone to the table, literally, and helping everyone see that their voice is equally important in solving these environmental problems and doing the research was really powerful,” Mendelson says.

Mendelson shares that she and her fellow faculty have also been developing their community-engagement skills in working alongside their students. “I’m amazed at how important relationships are, and trust,” Mendelson says. “Building relationships with members of the community has been much more interesting and complicated than I expected. It’s work. But it’s good work.”

That community engagement piece makes ICARE different from other environmental science programs, explains Kevin Omland, professor of biological sciences. “We’re definitely tackling different issues in different places than lots of environmental science has, even 10 or 20 years ago,” he says, “so it’s really satisfying to see that coming into place.”

“ICARE fulfills so many of the stated missions and goals of UMBC—to connect with community, to address the climate crisis, to increase diversity and inclusion,” Mendelson says. She looks forward to working with the second cohort of ICARE students, who started this fall, preparing them for successful careers in environmental science and leading local change.

Tags: Baltimore City, Biology, CAHSS, CNMS, GES, GradResearch, rca-2