On a chilly morning in early spring 2022, Eileen Meyer, Roy Prouty, and Erik Crowe were on the roof of the UMBC Physics Building. They were inside the observatory dome, trying to figure out what had gone wrong with the 32-inch telescope installed when the building was constructed in 1999. They had already determined that the shutters designed to keep dust off the mirrors were jammed, rendering the telescope temporarily unusable.

“So we’re up there with flashlights and ladders that are not quite tall enough,” Meyer recalls, “trying to figure out what is happening and realizing that some of the motors have died.” They weren’t terribly surprised, given the age of the instrument and the harsh conditions on the roof of a building: extreme heat in summer and cold in winter as well as high humidity. At one point, Meyer says, birds unfortunately had to be evicted from one of the ventilation grates, but not before they had spread debris around the dome.

As someone who decided as a first-year graduate student that hands-on lab work wasn’t really her thing, Meyer may seem an unlikely candidate for climbing ladders, ordering parts, and figuring out wiring as the observatory refurbishment lead. In fact, Meyer, associate professor of physics, has spent the better part of the last decade using computers (often the “super” variety) to conduct astrophysics research, mostly on black holes (the supermassive variety)—but she is finding fulfillment in expanding her work.

“That’s the beauty of having a career that is hitting its mid-stage,” Meyer says. “You can start trying different things.”

Leaning into the turning points

The telescope renovation project is a symbol of Meyer’s evolution as a scientist. Because it requires expertise outside her wheelhouse, it’s enhancing her management and delegation skills, she says, and allowing her to collaborate with a wider range of students and colleagues, including engineers. Plus, the upgraded telescope will enable other projects she’s diving into now, creating new opportunities at a turning point in her career, she says.

When it was built, the observatory was a state-of-the-art facility, designed to conduct observations of the near-Earth atmosphere and to serve as a public-outreach tool. The latter function is still underway today, with programming offered by observatory director and current Ph.D. student Roy Prouty, M.S. ’16, atmospheric physics, but the aging of the telescope and its original cameras means it is no longer up to the task of cutting-edge research.

With generous financial support from the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences and hands-on help from people like Prouty and Crowe, the Physics Building manager, Meyer says, “The goal is to modernize the observatory and bring it up to the level of something that we can actually put research-grade equipment on and do observations.”

The beauty of physics

While the details of Meyer’s research might be shifting, her overall drive to conduct research and create knowledge are longstanding and unchanged. “I always wanted to be a scientist from as soon as I knew what that was,” Meyer reflects—although astronomy was something “I fell into by degrees,” she says.

As an undergraduate at Rice University in Houston, physics won her over because “it’s so beautiful,” she says. “It’s this interplay of the natural world and the mathematical descriptions you can make of it. It can be deceptively simple.”

“And once you’ve been trained as a physicist, it’s something you can’t turn off,” she adds. “You’re driving down the highway, and you see something oscillating on a truck, and you start to think how you could model this with equations …You start seeing these things everywhere, and it explains to you why the world works the way it does. It takes away a lot of the mystery, but it does it in a beautiful way.”

Meyer initially pursued particle physics, thinking that was the frontier—the field where she could ask fundamental questions about the rules by which the universe operates. But after changing advisors early in her graduate career for a better personality match, she found herself in an astronomy research group, and has stuck with it since. “It turns out that astronomical observations allow us to constrain fundamental physics,” she says, “so it’s not like I went away from that after all.”

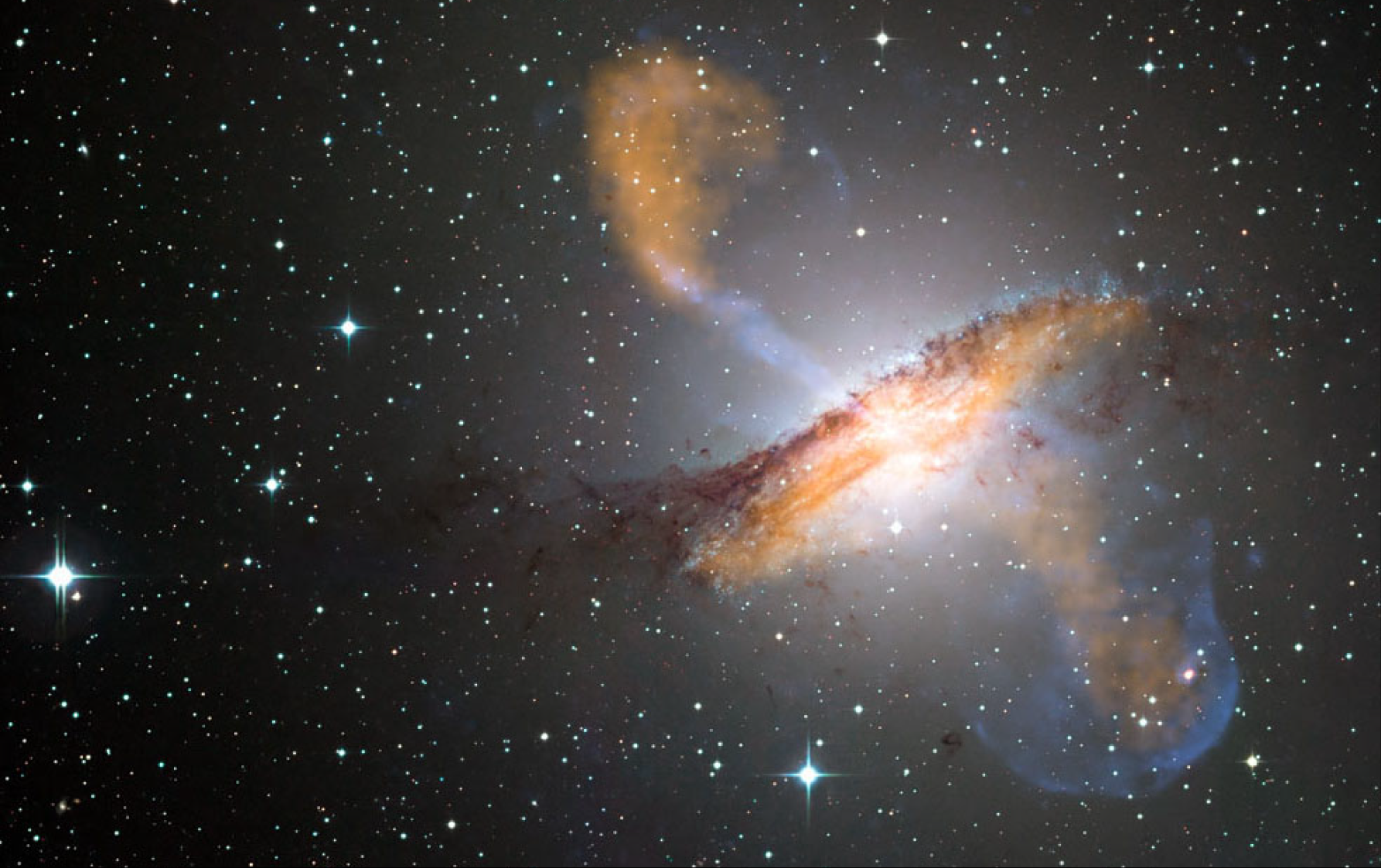

Plasma jets and giant mergers

To date, her work has largely focused on “understanding why black holes do what they do,” Meyer says, with a good deal of it focused on the giant jets of extremely high-energy plasma that often stream from them in opposite directions. The jets can be bigger than entire galaxies, carrying tremendous amounts of energy and material, Meyer explains. “And galaxies are enormous,” she adds. “Those themselves are already hard to imagine, they’re so big.”

Supermassive black holes, while denser than anything known in the universe, can have a volume about the size of our solar system. “It’s unbelievably tiny compared to the scale of the chaos that they’re unleashing” with their jets, Meyer says. The existence of the jets “was something that nobody predicted,” she adds. Even in the 1960s, some scientists were still arguing that black holes themselves (forget about their jets!) did not exist. Today, black holes are well established, but, Meyer says, “it’s still a major open question—how do they produce these jets?”

Black holes and their jets “are basically super extreme environments, so they’re interesting to study and to try to understand,” Meyer says. “There’s just major things that we don’t know about them. We’re hopeful we can understand them eventually, through observations and heavy-duty computational modeling—because that’s what they didn’t have in the ’60s. And even today, we regularly run up against the capabilities of what the computer can do.”

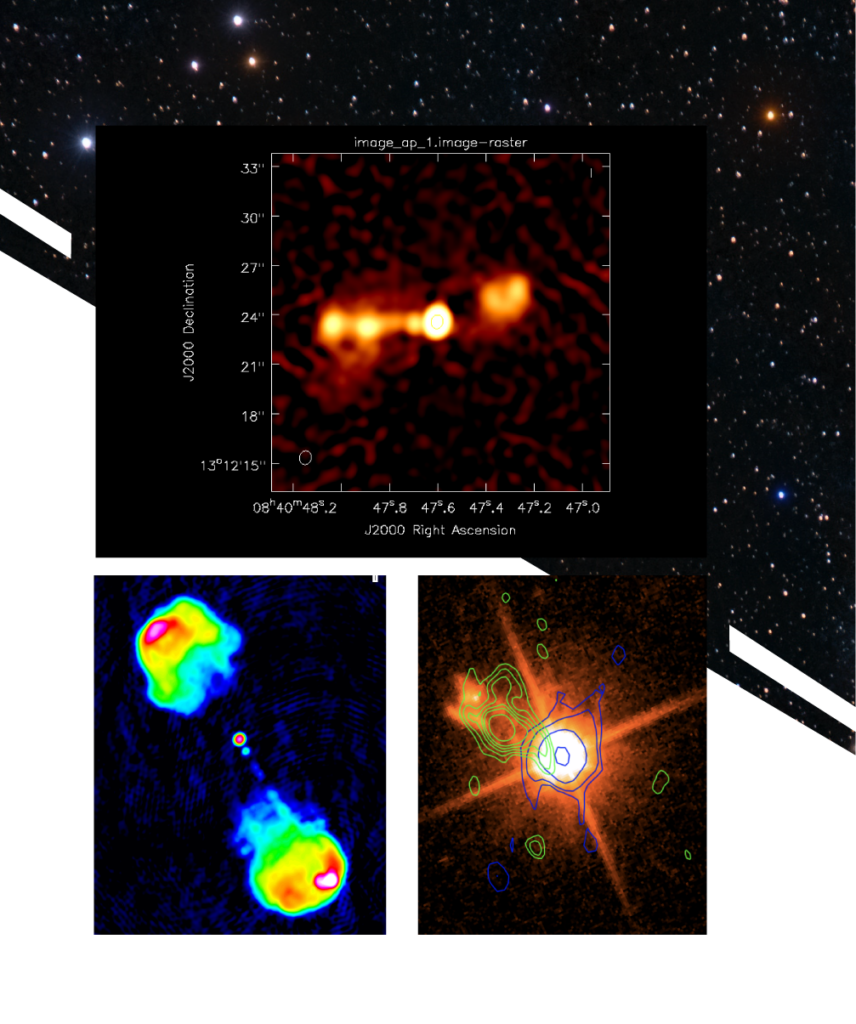

Meyer also studies black hole mergers—the combining of two black holes into one. It’s another research area fraught with uncertainty and with much left to discover. Recently, she co-led a project that found the most convincing evidence yet of a merged black hole that has been “kicked” out of the center of its galaxy, in this case, at 4.5 million miles per hour.

“The history of studying black holes,” Meyer says, “is just one surprise or ‘what the heck’ after another.”

Striking out on her own

As exciting and rewarding as studying black holes is, when asked about major milestones in her career trajectory, rather than naming the funding of a huge proposal or a publication that moved the needle in her field, Meyer turns to more intangible matters. After completing a Ph.D., which Meyer did at Rice in 2012, a researcher should transition to becoming truly independent in setting goals and priorities, bringing in funding, managing a research group, and going beyond “the projects your advisor wanted to do,” she says.

After a postdoctoral fellowship at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STCsI) at Johns Hopkins University under an inspiring mentor, Bill Sparks, Meyer joined the UMBC faculty in 2015. It would be the first time she had a “lab of her own.” Sparks was confident she was on a path to great things at the time. “It was a real pleasure to work with Eileen at STScI; we considered ourselves very fortunate to bring her there,” he says, adding that her work there “was extremely favorably received. An eminent astronomer described it as ‘truly beautiful work.’”

Yet, like new faculty members everywhere, at UMBC Meyer says she went through a period of proving herself— working hard to bring in major grants, come up with fresh research ideas, and publishing high-impact papers as a lead investigator. The first major milestone “felt like it happened eventually after I’d been here a couple years,” she says. “I felt like I could call myself an independent researcher.”

Independent, but not alone

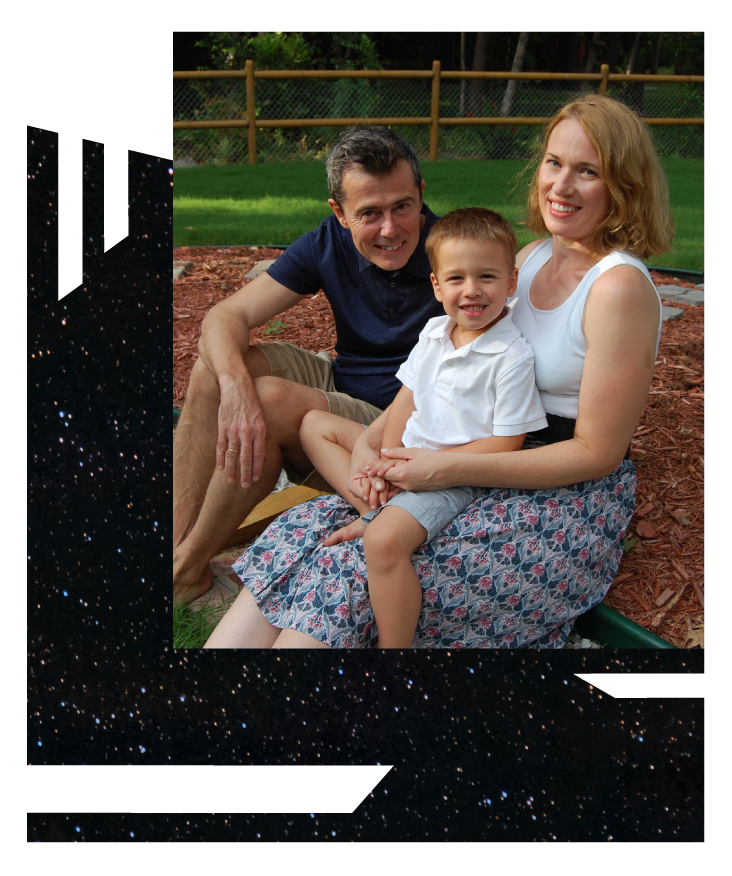

Even as she worked toward independence as a researcher, Meyer certainly wasn’t alone. Mentors like Sparks and Meyer’s husband, Markos Georganopoulos, professor of physics at UMBC, and others in the department and at the university have provided support along the way.

“He was a little bit ahead of me in the career stage,” Meyer says of Georganopoulos, “so everything I would go through he had gone through a few years before. You can kind of mentor each other because you have a sounding board.” Their research is similar enough that Georganopoulos is a co-author on some of Meyer’s publications.

Jane Turner, former director of the Center for Space Sciences and Technology, a UMBC partnership with NASA, also mentored Meyer in her early days at UMBC. “I’ve come to appreciate that UMBC is a very supportive place—the department, the college, and the school in general,” Meyer says. “It’s absolutely true that people want you to succeed here. I’ve always felt that.”

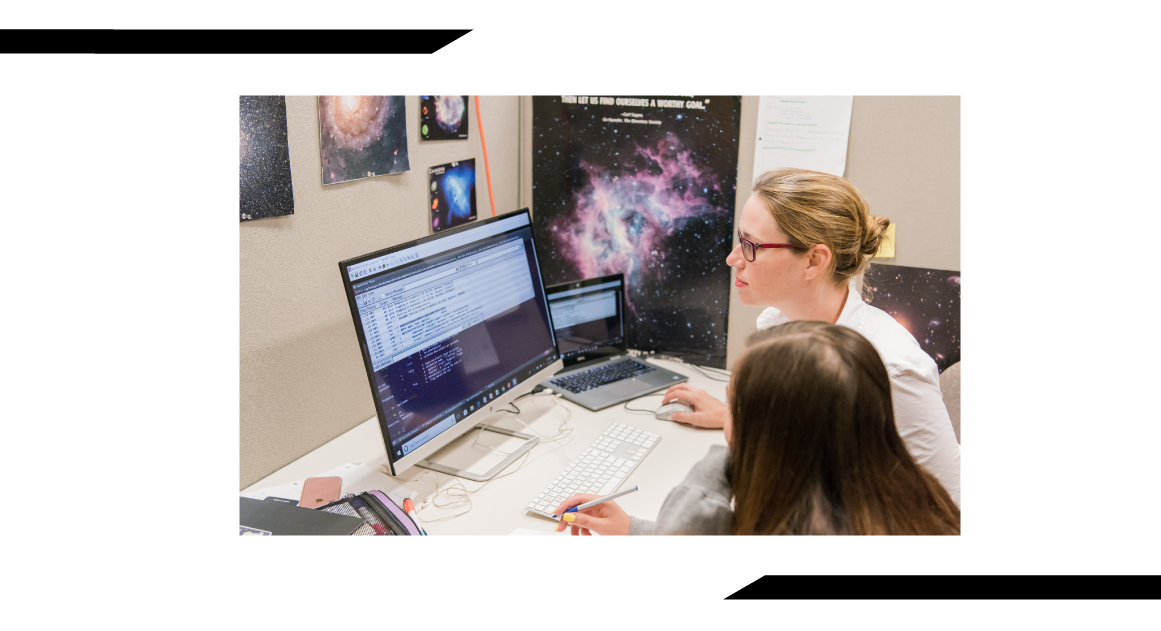

Meyer understands the importance of mentorship, as the first person in her family to earn a Ph.D. She enjoys paying that support forward to UMBC students. “I really love our student population. They’re just fantastic,” she says. “There’s a certain seriousness and maturity that they have that I really appreciate.”

Some of her students are the first person in their family to earn a college degree, and many more, like Meyer, are the first in their family to be considering graduate school. “I feel like I identify with our student population, which makes working with them really a joy.”

Life as a parent-researcher

In 2019, Meyer and Georganopoulos welcomed their son into the world, and she felt the strength of the UMBC community even more. “Parenting and being a highly active researcher is a real challenge,” Meyer says, especially when you’ve moved far from family in order to pursue your dream of being on the faculty at a research university. While “the department and UMBC in general has been very helpful,” parenting still hasn’t been easy given “systemic bigger issues that we have with supporting parents,” she says.

Always a determined problem solver, however, Meyer has found ways to succeed both as a parent and as a scientist. Mentors advised her to consider all of her unfinished projects (of which any researcher usually has many), and instead of trying in vain to complete them all, “focus on where you can make major progress in the field. Focus on impact, and let the others go,” she says. She has taken that advice to heart—especially through the pandemic.

And now that she’s more established in her field and as a researcher, it’s time to step back from the “take every opportunity” mentality and learn to say no, which can be a special challenge for women and young scientists, Meyer says. “Bill [Sparks] was always very good at that,” though, she adds—and that’s not the only thing she’s taken from his mentorship.

“He is my model for what a scientist should be,” Meyer says. Especially with current pressures to publish and win grants at a rapid clip, Sparks “always did only what he was interested in,” even shifting focus from astrophysics to astrobiology later in his career. “I want to be as free as he is with how he does his work,” Meyer says.

Living the freedom

Today, Meyer is living that freedom by exploring new kinds of research using the UMBC observatory, and Sparks has joined UMBC as an adjunct faculty member to support the effort. In addition to fixing up broken motors and buying a much larger ladder, Meyer plans to build a new instrument called a polarimeter, which will make observations of objects in our solar system, phenomena farther away such as flare stars, and other targets possible with the UMBC telescope.

“It’s great to be working with Eileen again—she’s so darn good at everything and always open to taking on something new and unfamiliar, whether it’s building polarimeters, climbing wobbly ladders, or thinking about black holes and the origin of the universe,” Sparks says. “Eileen is one of the most capable and versatile researchers in astronomy—and our project should keep UMBC at the forefront of a unique, innovative scientific niche.”

Making new missions happen

She is also on the leadership team of a University of Maryland-led consortium competing for NASA funding for a new space-based satellite mission. NASA put out a call for proposals for high–energy astrophysics missions, and her team’s entry, the Advanced X-ray Imaging Satellite (AXIS), would capture extremely high resolution X-ray images to study galaxy formation, black holes, and much more.

This role is an exciting change for Meyer. She describes herself as coming from “a classical academic path,” where she relied on data from both land- and space-based instruments but was never involved in their design, construction, or the bureaucracy often involved in actually putting a satellite in the sky. After attending a summer workshop at Harvard, however, her perspective shifted. A scientist on the original Chandra X-ray Observatory mission team gave a talk describing the iconic mission’s 30-year journey from concept to launch, which finally happened in 1999.

“I was astounded by how difficult it was—the immense challenge—but then also how amazing it is that eventually this thing flew, and it’s still working—it’s still taking amazing images all the time,” Meyer says. “Ever since then, I always thought I would love to get involved in that process, to help be an advocate for new observatories, new technologies. So when I was asked to join AXIS I was very happy, because it’s been a long-term side dream of mine to be involved in making new missions happen.”

The things that are mine

As her career—and her family—moves forward, Meyer is hitting her stride. “I love studying black holes and jets, but it’s still true that that was my advisor’s topic,” she says. But with AXIS, the observatory work, and other new collaborations, “I feel like I’m getting into the things that were really mine—the things that were interesting to me all along,” she says.

The UMBC physics department plans to hire at least one more faculty member in high-energy physics soon. That could also shape Meyer’s work, depending on her new colleague’s areas of interest. She’s also been approached by researchers in the Center for Space Sciences and Technology for collaboration. Put simply, the future is bright for Eileen Meyer, and she’s savoring it all.

“I think of myself as an open person; I could see myself doing work that I haven’t imagined yet,” she says. “I like it when people bring me problems to think about. We’ll see where we go next.”