The notion of the “American dream”—that hard work can lead to social and economic mobility—has existed in the United States for centuries, and it has been disputed for almost as long. Pamela Bennett’s new book, Parenting in Privilege or Peril: How Social Inequality Enables or Derails the American Dream (Teachers College Press, 2021), takes on this idea. Bennett, associate professor of public policy, explores some of the social, educational, and economic factors that impact the decisions that middle- and working-class parents make in hopes that their children can attain the “American dream.”

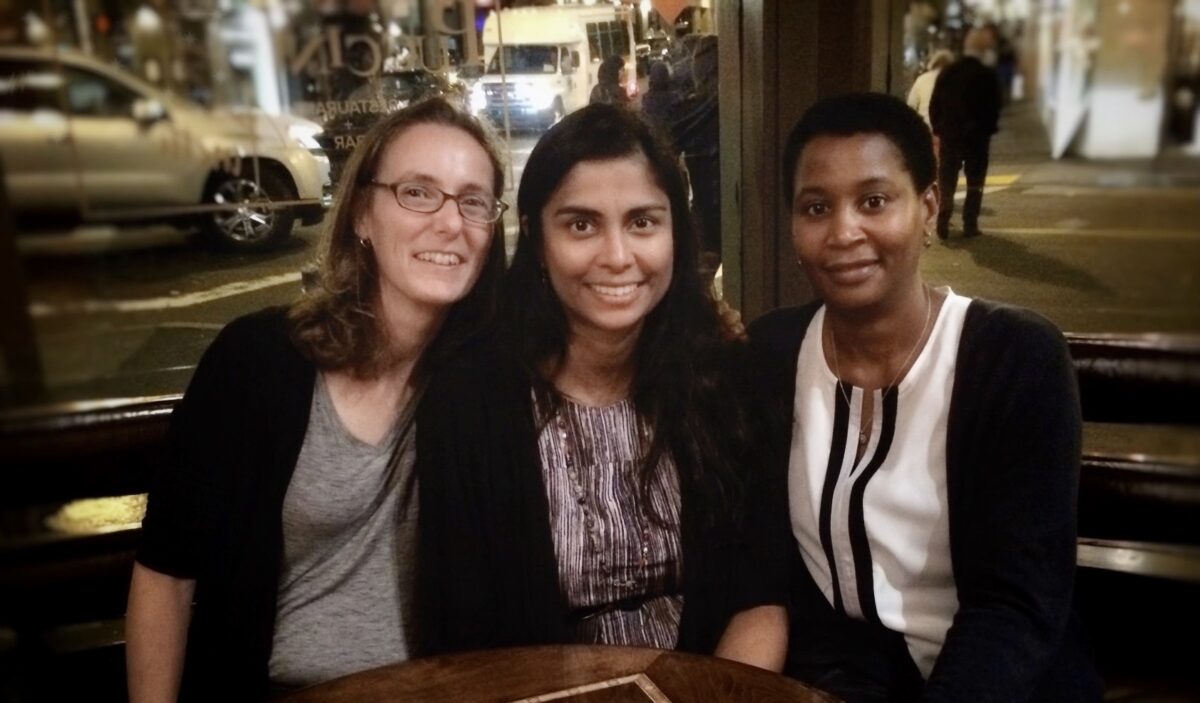

Bennett co-authored the book with Amy Lutz, associate professor of sociology at Syracuse University, and Lakshmi Jayaram, founder of the Inquiry Research Group LLC and research associate with the University of Central Florida.

“We designed a research project to investigate the role that culture and social inequality play in the educationally relevant parenting strategies of working- and middle-class parents,” explains Bennett.

After interviewing 50 parents from two public schools in a northern U.S. city, they found that middle- and working-class parents generally engaged in two types of parenting: defensive and strategic parenting.

Beyond the parent interviews, family survey data, census data, local police data, school climate data, and social network data provided further details about the economic resources parents had access to and the social conditions that impacted their wellbeing.

Defensive and strategic parenting

These two parenting approaches emerged when the researchers explored parents’ “values, orientations, and expectations” for their children’s educational journey as a pathway to achieve the “American dream.” Parents shared their lived experiences within their neighborhoods and schools, as well as work, social, and educational networks.

The data show both middle- and working-class parents share a goal of having college-educated children. However, the resources accessible to each group vary widely, as do the social conditions in which they live, which ultimately influence how the parents approach this goal.

Middle-class families with large social networks and economic resources were more likely to practice “strategic parenting” by making key decisions leading to their child’s academic improvement, new skill development, and variety of extracurricular activities. Their decisions were influenced by access to many choices and to safe neighborhoods and schools that helped parents nurture their children. This social context encourages adolescent independence and the personal growth needed to attend college.

On the other hand, working-class parents in the study had more limited access to financial, social, and enrichment resources. They also had to consider how their child would engage in a world where neighborhoods and schools contain serious safety concerns. These safety concerns lead some parents to heavily monitor their teenagers’ interactions with peers and other adults and to shield them against actions that might limit their opportunities.

In this way, working-class parents generally practiced “defensive parenting,” making decisions that protected their children from harm while also working toward their social mobility.

Public impacts

The researchers hope this study can inform education policy designed to close the gap between working- and middle-class families’ access to the “American dream.” One key way to achieve this, Bennett suggests, is increasing neighborhood safety and access to academic enrichment activities.

Bennett’s work on social inequality in higher education and racial residential segregation spans two decades. This new book comes on the heels of several recent articles she has co-authored on topics related to affirmative action and collegiate outcomes, college entrance exams and academic performance, and talent loss among Blacks and Latinos following affirmative action bans. She and Amy Lutz will soon publish a new article, in Harvard Educational Review, on whether state bans differently affect the willingness of Black, White, Latinx, and Asian Americans to apply to selective colleges.

Recently, Bennett spoke about college access and affordability on Marketplace, a public radio show heard by more than 14 million listeners each week. She recommended hotlines for students and their families to ask questions about financial aid and direct support with completing FAFSA applications, particularly for first-generation college students. “The stakes are talent loss, frankly, for the country,” Bennett said.

Feature image: Pamela Bennett. All photos by Marlayna Demond ’11 unless otherwise indicated.

Tags: CAHSS, cahssresearch, CS3, PoliticalScience, Research