It’s a mere hour after sunrise, and Wajhee Zaidi, a student at Howard Community College (HCC), is out in his neighborhood, looking for birds, insects, and whatever other critters he can spot. “Never would I have thought that I would go out at 7 a.m. just to look for different species of animals,” he says. “It got me out of my comfort zone.”

Zaidi’s early morning birding and bug-hunting was part of a three-week program collaboratively organized by HCC and UMBC. The practicum immersed HCC students in an authentic environmental science research experience and helped them connect with UMBC faculty.

Orioles and orb weavers

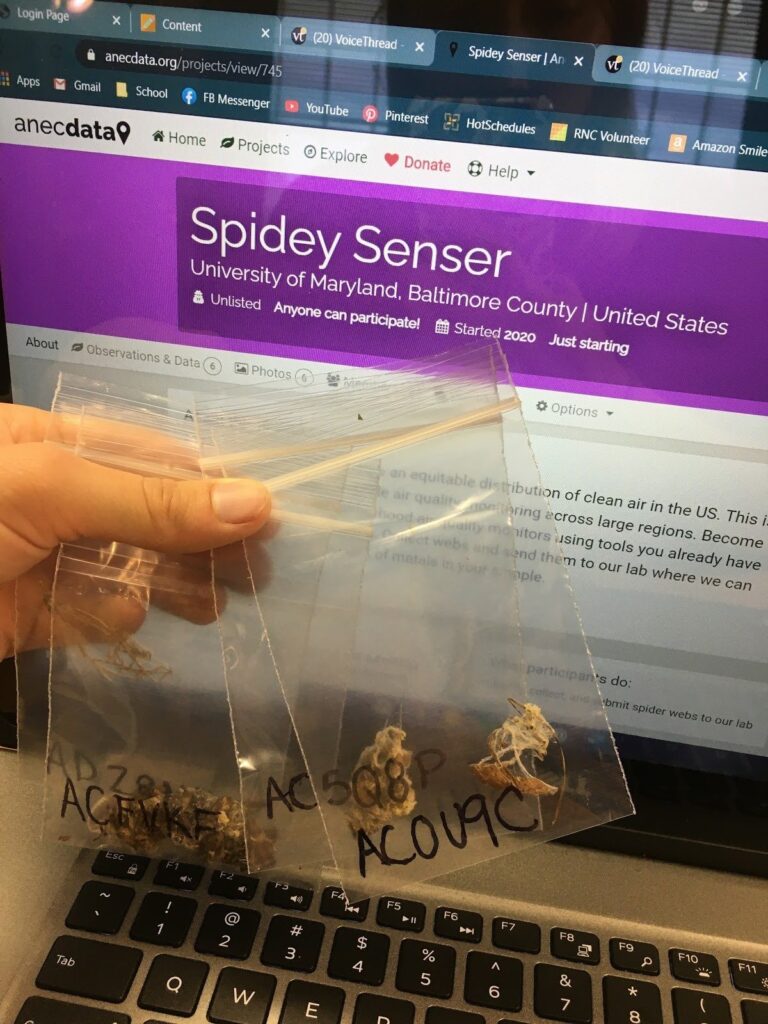

Each morning, Kevin Omland, professor of biological sciences, and Chris Hawn, assistant professor of geography and environmental systems, guided the students through activities like analyzing data on Caribbean orioles, collecting spider webs for air quality monitoring, and safely seeking out and documenting local creatures.

The students gained foundational research skills like observation, data collection, and collaboration. They also made real contributions to research and service projects. “They participated in three ongoing scientific research projects, all from their living rooms,” Hawn says.

As part of a service-learning project for Baltimore Green Space, the students created tutorials about how to use the iNaturalist platform. And Omland shared their analysis of the interactions between the endangered Bahama Oriole and the parasitic Shiny Cowbird, which lays its eggs in other birds’ nests, with his lab’s research partners at the Bahamas National Trust.

Hawn also asked the students to test protocols for a program designed to help communities take greater control of their air quality. Hawn has found that analyzing the chemistry of spider webs works well as a proxy to measure hyper-local air quality, and they’re launching the program in Baltimore and Portland, Oregon in partnership with a non-profit. This project also introduced the students to the importance of citizen science.

“My goal for the students was to capture what I think is the most important part of scientific research—curiosity through observation,” Hawn says. By training their eyes and learning to see in new ways, Hawn says, “People were making discoveries literally inside their houses, or on a walk, or in their yard. It was really wonderful to see that transformation.”

“It was great to have this real, authentic experience,” shares Mary Lenahan, an environmental science major at HCC and an aspiring reptile field researcher. “I didn’t realize I’d be able to learn this much in just three weeks,” she added, a feeling echoed by the other participants.

A broader view

“This experience has broadened my view of research,” says Oluwasemilore Oluwagbenro, a general studies major at HCC who wants to be a doctor. “Researchers aren’t just either looking at the internet and books or confined within the four walls of a laboratory—research can also be walking in your backyard.”

Beyond expanding their perspective on what research can be, the summer experience offered new insight shaping how the students imagine their future careers.

Pilar Thomas, a life science and nutrition major at HCC, says, “This research experience helped me get to know this whole sector of biology that I hadn’t really looked at at all, because my biology classes focused on human biology and physiology.”

Zaidi, who also plans to pursue medicine, agrees. “Understanding all life and species plays a big part in medicine, so I think this definitely helped me toward my career goal by offering some insight and background knowledge.”

Oluwagbenro put it simply: “In the end, who is a good medical doctor without understanding the environment?”

Digital fluency

In addition to learning quite a bit about birds, spiders, and the scientific process, the students gained digital skills. They became proficient in Blackboard, UMBC’s learning management system, and learned how to use various online tools for their culminating project, a digital story.

Thomas was excited and surprised to learn more than science. “Prior to this research collaboration I could barely take a video on my phone,” she says, “so it was so cool to go through the process of making a final digital story, using screenshot slideshows, screen recordings, and everything. I would never have thought I would gain those types of skills in three weeks, so it helped me learn more about myself as a student, too.”

Enthusiasm “right through the screen”

The students and their instructors were surprised by the strong connections they were able to forge online. Hawn and Omland set the tone for a collegial, challenging, and fun experience. “I like to say that I throw them in the deep end and then cheer really hard and give them good advice,” Omland says with a smile. With Omland and Hawn’s coaching, the students learned to swim quickly.

“They expected a lot from us, and they also answered any questions we had. We had a lot of fun moments,” Thomas shares, “and with Dr. Hawn and Dr. Omland, I definitely felt connected.” Lenahan agreed, saying that working with the faculty was “like talking to a colleague.”

As colleagues, the group worked on solving problems together. “Like real research, there were problems. We had to figure out different ways of doing things,” Omland says, from teaching the students how to identify birds, to collaboratively working to find the best way to display their data, all without being together in person. “I gave them plenty of responsibility, and they came up with great solutions,” Omland says.

Omland and Hawn’s excitement for their work also made a powerful impression on the students. “We got to know them as people, and to know why they were passionate about this and what drove that fascination,” Thomas says. “You could just feel their enthusiasm through the screen.”

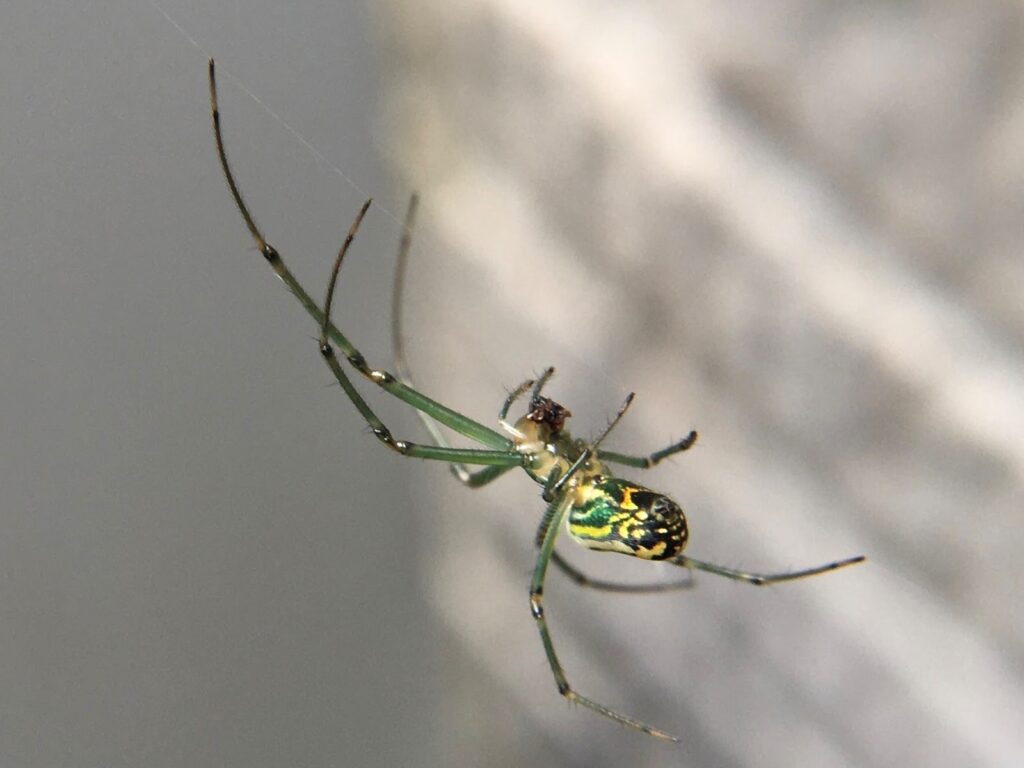

For example, “I was telling Dr. Hawn about this spider that I found with this really awesome web, and they started telling me all about it,” Lenahan says, “and you could really see the joy that they had knowing that I experienced the same sense of awe that they had about these creatures.”

A VIP view

Even though the students weren’t physically on campus, the summer program gave them plenty of chances to get to know UMBC. Each afternoon, a panel discussion with staff and faculty from different departments introduced the group to a different aspect of the university.

Scholars programs, service learning, academic support opportunities like the Writing Center and advising, financial aid, and admissions all made an appearance. So did the Initiatives for Identity, Inclusion, and Belonging, which includes the Interfaith Center, Pride Center, and Mosaic Center; and resources for transfer and commuting students, like the Transfer Student Network and Off-Campus Student Services.

Learning about the transfer process “made everything smoother, because you’ve met all the right people already,” Oluwagbenro shares. Thomas adds, “The transfer department talked to us about everything, like financial aid, and applying, and how to get involved early with the Transfer Student Alliance. That really helped solidify everything.”

The panels were even tailored to the particular students participating this year, several of whom are interested in medical careers. By getting to ask questions about academic preparation for health professions and learn about research opportunities with faculty in different departments, “We got a VIP view of UMBC, which was really cool,” Oluwagbenro says.

Collaborative creation

All the elements of the program worked together to help prepare students for transfer—to UMBC or another institution. “We want to give students lots of opportunities to think deeply about their educational goals and trajectories,” Sarah Jewett says, “but also to build the skills, knowledge, and connections that will really help them to transfer more successfully.”

Jewett, director of innovations in transfer research and practice, designed the summer program in collaboration with Hawn and Omland, as well as Charlotte Keniston, Kasey Venn, and Emily Passera at the UMBC Shriver Center. Jewett learned about birds and spiders alongside the students, and the students appreciated her engagement throughout the experience.

As with last year’s program in Baltimore’s urban forest patches, Patricia Turner, Dean of Science, Engineering and Technology at HCC was a critical partner in the summer program. She recruited the students and provided the field supplies for their investigations.

Expanding and evolving

The program, funded by the UMBC provost’s office, has so far focused on environmental science research themes. Now, Jewett is brainstorming ways for it to evolve. This year’s model, with multiple, one-week sessions on thematically connected topics, could translate well to other disciplines. “What might that look like in history, or in art, for example?” Jewett asks. She’s already been meeting with UMBC faculty in other departments to explore options.

The program’s format might also evolve to meet more students’ and instructors’ needs. “Last year, we were completely outside for eight weeks, and now we’ve been completely online for three weeks,” Jewett reflects, “So now, where do we mix those pieces together? What would a hybrid model look like for next year?”

For now, at least these four students have found new opportunities, new ways to think about science—and even new neighbors in their own local environments. Lenahan, for example, spotted a basilica orb weaver and its dome-shaped web near her house for the first time.

“I love nature and going out and exploring, so the fact that there was this common spider in my backyard that I had never noticed before was so weird to think about.” Lenehan’s orb weaver is much like UMBC to many students at the region’s community colleges—compelling and right in their backyard, yet sometimes not on their radar. Thanks to this summer’s UMBC-HCC partnership, these students are seeing the possibilities.

Banner image: An American Goldfinch perches at a bird feeder. Photo by Jim McGlone. Used under CC BY-NC 2.0

Tags: Biology, CAHSS, CNMS, GES, Undergraduate Research