“How can Baltimore neighborhoods renew themselves without forcing out local residents or homogenizing diverse populations?” Community-engaged researchers from UMBC, Morgan State University, and the University of Baltimore will examine this question through a Dresher Center Humanities Forum panel discussion on “Redevelopment and Justice in Baltimore,” held in the Albin O. Kuhn Library Gallery, April 18, 2018, 4 – 5:30 p.m.

Panelist Nicole King, associate professor of American studies, has worked with her students to document and understand the diverse stories of Baltimore’s people and places, producing the radio series Bromo Speaks and Downtown Voices, and the project A Journey Through Hollins. King’s classes examine the complex web of social, economic, and political issues involved in gentrification, based in the idea that better understanding the perspectives and experiences of current Baltimore residents can lead to more collaborative and just planning and policies.

“There is a lot of discussion about how we need more millennials to move to the city. Freddie Gray was a millennial,” explains King. “Young people need to be able to see through the boosterism, coded language, and the so-called Baltimore ‘renaissance.’ We need to rethink the public’s right to the city.”

Joining King on the panel will be Felipe Filomeno, assistant professor of political science at UMBC; Lawrence Brown, associate professor of community health and policy at Morgan State University; and Seema D. Iyer, associate director and research assistant professor at the University of Baltimore’s Jacob France Institute.

Brown agrees with King on the importance of challenging the many misconceptions about what gentrification is, why it happens, and how it impacts residents physically, socially, economically, educationally, and emotionally. “Baltimore is the largest city in the state and there are many narratives that tell the story of who lives in Baltimore. Without understanding what has happened to Black communities in Baltimore, these narratives become victim-blaming,” notes Brown. “They miss how systems by our government have played a pivotal role in disrupting and uprooting entire communities until they were fundamentally unstable.”

The panel describes gentrification behaviors as the influx of private and/or public capital in a targeted area that then triggers an increase of education levels, income levels, housing prices, and a higher proportion of white residents. “When you see these markers of gentrification it is not a solution for existing communities who are waiting for safe and affordable housing,” says Iyer. “Baltimore has a housing crisis. There are 25,0000 households waiting for housing assistance. The house you have, which you may not be able to afford, is all you have because there is little economic relief or safe, affordable housing alternatives.”

The immigrant population in Baltimore has been impacted in a similar way, says Felipe Filomeno. He partnered with the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant and Multicultural Affairs from 2016 to 2018 evaluate Baltimore’s policy to attract and retain immigrants, examining education, health, public safety, and housing. Filomeno explains that nationally, immigrant homeownership rates are lower than the native-born population, making them more vulnerable to the effects of urban renewal. These communities are pushed out by increasing housing costs or by urban redevelopment that creates expensive amenities inaccessible to existing neighborhood residents.

“Immigrants forced out of Southeast Baltimore lose access to schools trained in teaching Spanish-speaking students and to community organizations that help connect them to jobs, health care, and housing resources,” says Filomeno. “Gentrification is a way to perpetuate inequality by cutting residents from the social and economic networks they need to experience some upward social mobility.”

The panelists will also look toward the future, discussing possible strategies to lessen the negative impacts of redevelopment and the gentrification that can result. Brown is hopeful about a proposal for the Perkins Homes near the Inner Harbor, where the housing authority will place residents in temporary housing before demolishing and rebuilding the development, and will then allow them to move back, to avoid displacement at any stage. Filomeno sees an answer in expanding homeownership programs for immigrants in neighborhoods across the city and county that need to increase their census. Iyer suggests a focus on maintaining diverse neighborhoods with a balance of different income and educational levels, as well as demographic factors, like race and age.

King wants Baltimore to take a different approach. Instead of focusing on enticing wealthier people from outside Baltimore to move to the city, she hopes the city can shift its strategic focus to the needs and great potential of current residents. She is setting her mind on educating and motivating thought leaders to rethink what community and success mean in Baltimore.

“We need to rethink the city for the 21st century,” explains King. She argues, “Baltimore should serve its current residents first and foremost. We need our politicians to show the same spunk of the city’s residents and to be up to try new things.” To do this, King suggests city leaders “listen to residents that have been here for generations, new residents ready to fight for a right to the city, and the young ones who will really shape the cities of the future.”

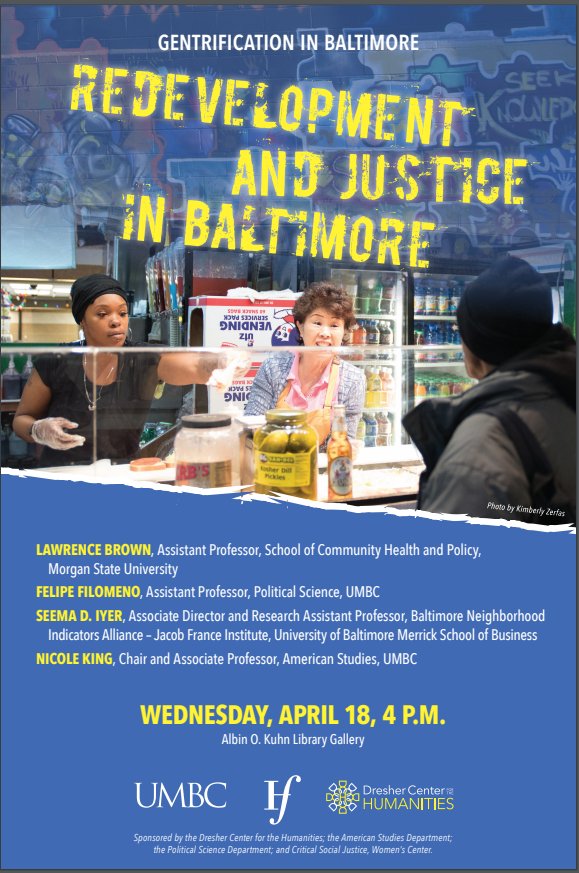

Banner image: Lexington Market, by Kimberly Zerfas.

Tags: AmericanStudies, CAHSS, diversityandinclusion, DresherCenter, PoliticalScience