After keeping scientists on their toes for weeks, the Larsen C ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula parted with a trillion-ton iceberg the size of Delaware on July 12. Chris Shuman, research associate professor at UMBC’s Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology, closely followed the rift in the shelf leading up to the iceberg’s separation, and offered expert comments in the media about this complicated milestone.

Although the calving event is momentous, Shuman thinks an imminent collapse of the rest of the Larsen C ice shelf is unlikely. “At this time we don’t see any signs this is going to cause any further breaks,” he told Vox. “On the other hand, this is over 10 percent of the ice shelf area, so that’s not a good sign.”

Scientists will be watching for other signs of ice shelf instability, including accelerating glacier movement, new rifts, and melting pools accumulating on the glacier’s surface, Shuman explained to Buzzfeed. He told The Baltimore Sun that if any of these signs appear, “That would begin to tell us that, ‘Hey, things are probably going to change more in the future.’” Regardless, “The big picture is clear,” Shuman told WJZ-TV. “Changes are happening.”

One factor that makes the broader collapse of Larsen C less likely is that the shelf is still strongly anchored to the continent at the Gipps and Bawden Ice Rises. “If we had seen the Larsen C lose connection with these grounding points … that would have been much stronger evidence the whole shelf is becoming destabilized,” he told Vox. While signs of accelerated breakup are currently lacking, Shuman says scientists will be watching the shelf closely. If it were to collapse, it would contribute to rising sea levels.

It’s currently unclear how much climate change influenced this particular iceberg’s release. “I myself don’t see clear evidence convincing me that this [specific break] is climate change-related,” Shuman told CNN. “Yes, the Larsen C will have retreated farther west than we’ve ever known it to have retreated before. On the other hand, it has dropped large [bergs] before,” he added on CBC News, noting the last time Larsen C released an iceberg of comparable size was in 1986.

Scientists seeking greater clarity on this iceberg and the future of Larsen C will closely monitor the situation as it continues to shift over time, Shuman notes. “You can think of the Larsen C or really any ice shelf like it is a cork in the neck of a champagne bottle lying on its side,” he told NASA Earth Observatory, re-quoted in Christian Science Monitor in February. “Once you pop that cork, the wine inside – all that glacial ice sitting on land – will start flowing out. And that’s worrisome because such thinning land ice is directly increasing global sea levels.”

Moving forward, Shuman will carefully track the iceberg via satellite imagery as it travels north and east. He expects it to take a path toward South Georgia Island, a British territory east of the southern tip of South America, but that’s not guaranteed. Icebergs like this “kind of bump along over a number of years,” Shuman told the Boston Globe. “The other thing is, of course, it may run aground. It’s going to take a period of years to watch this berg’s journey from start to finish.”

Despite, or perhaps because of, the uncertainties, Shuman shared with the Globe that “watching the evolution and release of this new large iceberg from the Antarctic Peninsula has been a truly humbling and awe-inspiring experience.”

Read more of Chris Shuman’s comments on the iceberg in CBC News, Buzzfeed, The Baltimore Sun, The Boston Globe, Patch, Vox, Forbes, PRI, Christian Science Monitor, KPAX-TV, La Tercera, VOA Noticias, WJZ-TV, CNN, and Motherboard. NASA’s Aqua satellite initially spotted the complete break, and the agency posted its own feature.

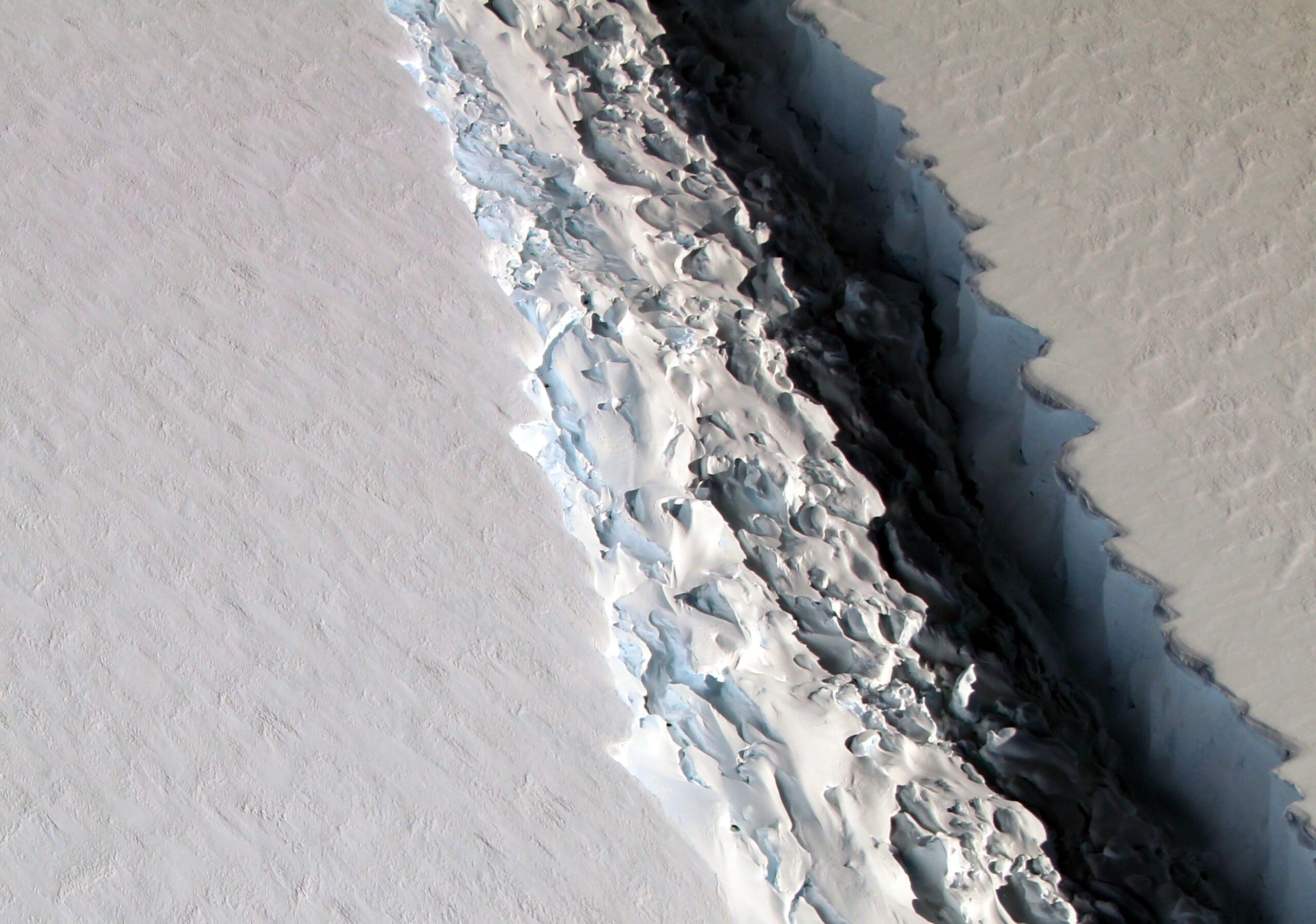

Image: A close-up of the rift in the Larsen C ice shelf from November 2016. Photo by John Sonntag for NASA.