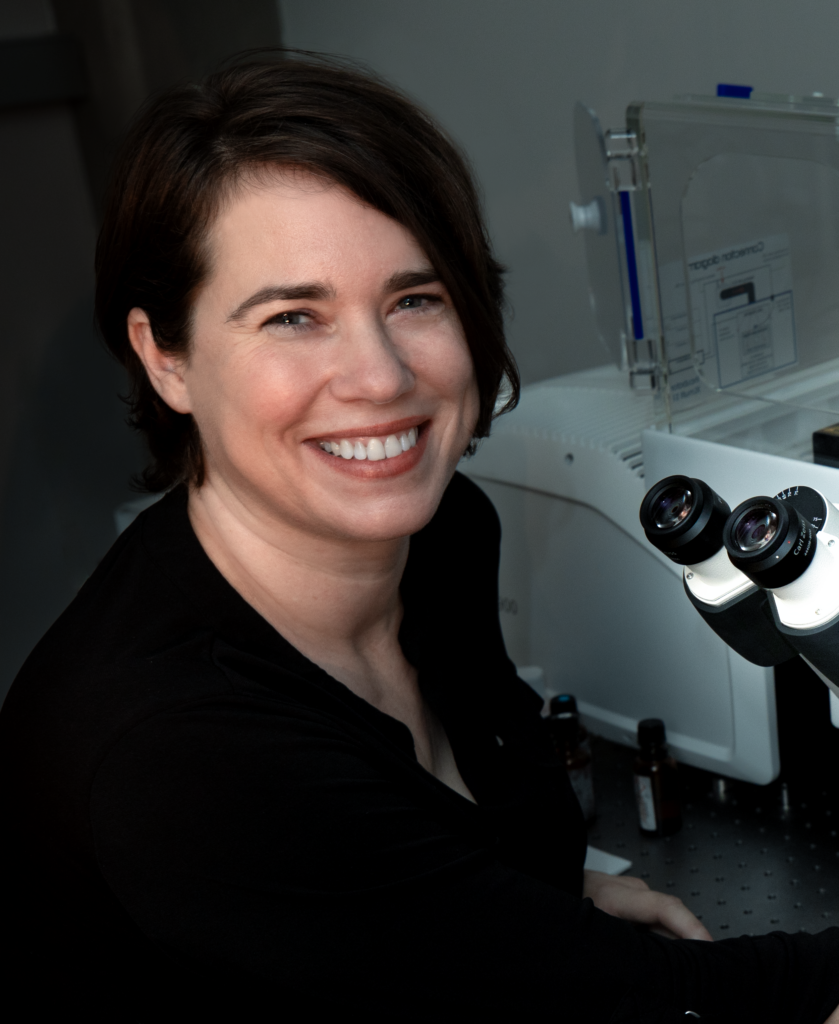

Tagide deCarvalho, director of the Keith R. Porter Imaging Facility in UMBC’s College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, produces artistic images that reveal microscopic life in vivid, thought-provoking ways. Her work combines her skill at the lab bench and behind the microscope with her artist’s eye, and it continues to earn her accolades worldwide.

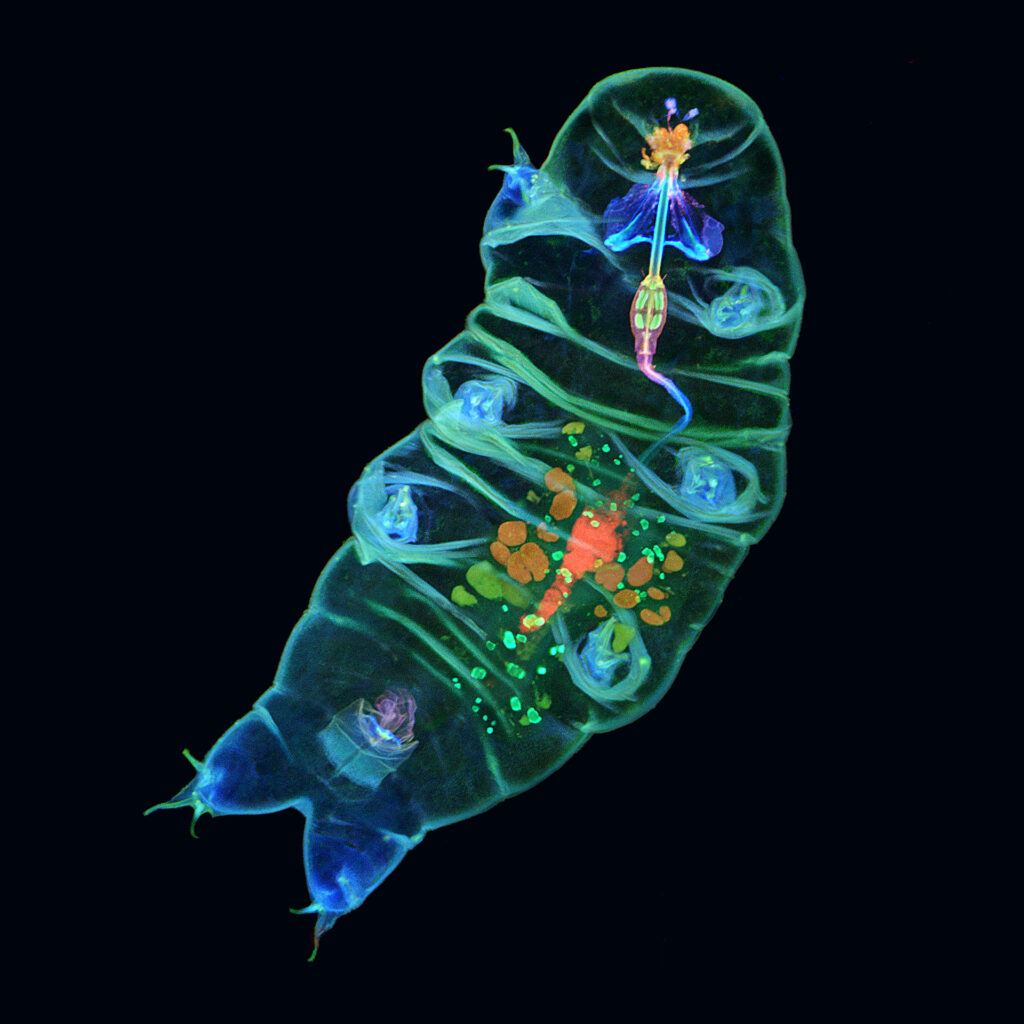

deCarvalho has been recognized repeatedly in the Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition. In 2020, she won the 2019 Olympus Image of the Year Global Life Science Light Microscopy Award for an image of a tardigrade, also known as a “water bear.” This year, she won the 2022 Zeiss Microscopy Image Contest in the Life Sciences category.

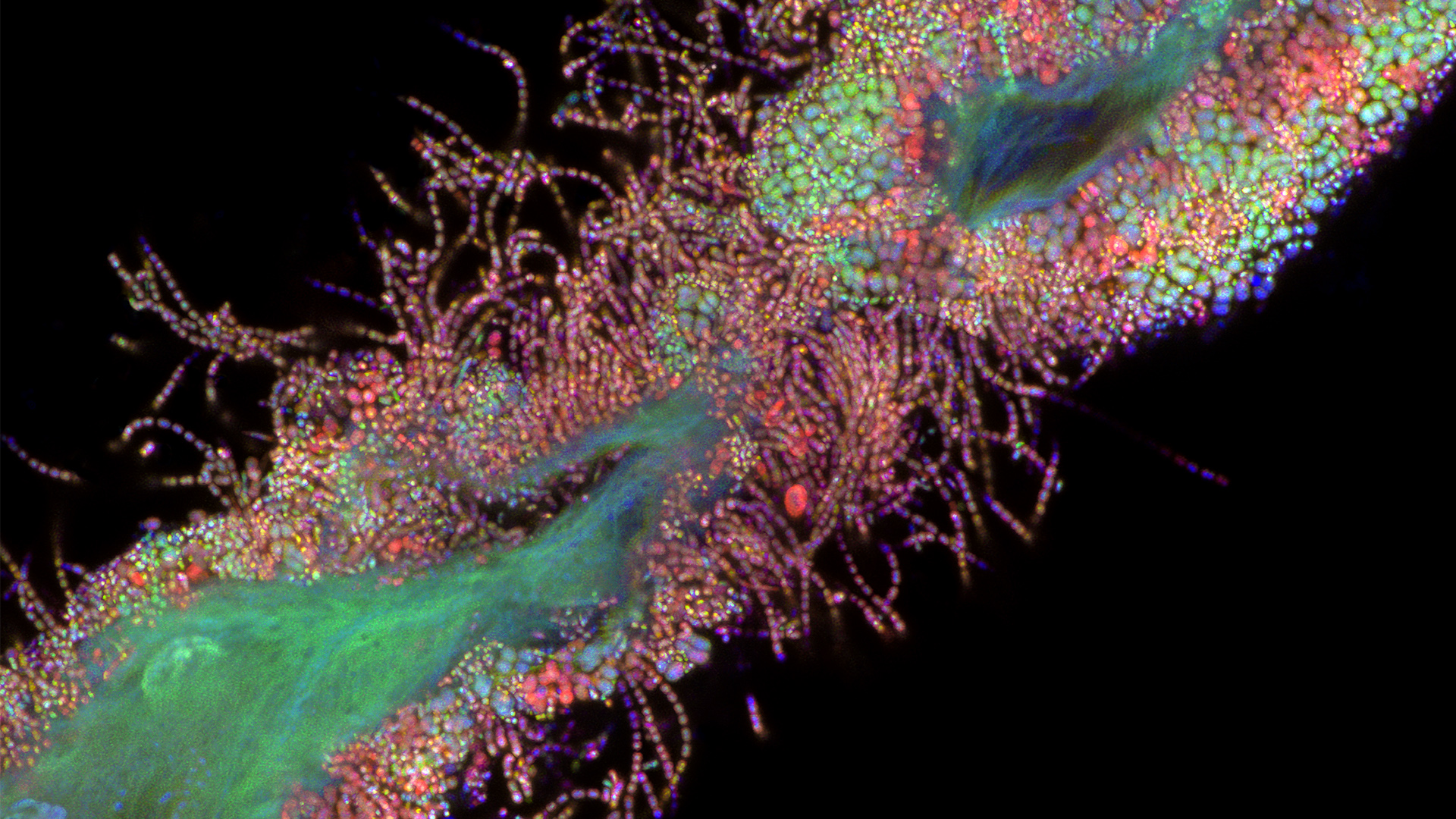

“We use their equipment. I’m a big fan of their instruments, so it was nice to be recognized by that company,” deCarvalho says of the Zeiss award. The winning image portrayed bacteria that she scraped from her own tongue. At the time, she simply needed a quick sample to test some new materials for preparing specimens in the lab. Only later did she decide to refine the image into something beautiful.

“My superpower is finding everyday specimens and making them glamorous,” deCarvalho says, a bit tongue in cheek. She recently learned that her images will now reach a larger audience than ever before.

Putting her stamp on the art world

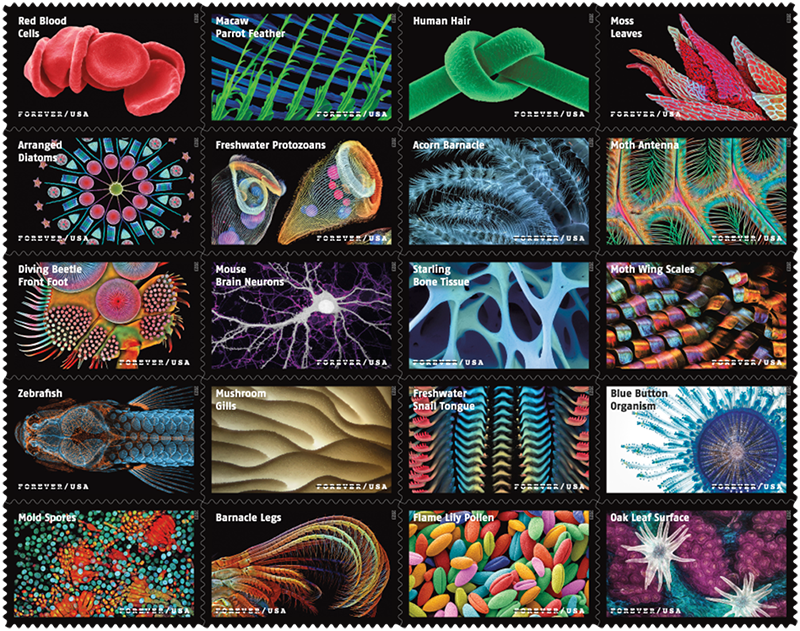

This summer, deCarvalho received an exciting request: An art curator wanted to include two of her images in an upcoming collection—except this was no typical art exhibit. A United States Postal Service (USPS) curator wanted to include deCarvalho’s work in a stamp collection featuring microscope images. USPS officially announced the “Life Magnified” collection in December, and the stamps will become available later in 2023.

The USPS recognition holds special significance for deCarvalho, whose grandfather collected stamps. When he passed away, deCarvalho inherited his collection. Her grandfather was a physician-scientist, and deCarvalho enjoyed looking through his microscopes as a child. He always told his granddaughter she would be a scientist one day.

deCarvalho has had a lifelong interest in art, too, and began her academic career as an art photography major. As an undergraduate, she wanted to learn to use microscopes to create art in a biological context. To that end, she worked for a faculty member at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine creating transmission electron microscope images.

The professor was thrilled to work with a student who already knew how to develop film—the hardest thing to teach, and something deCarvalho had been doing for years in her own darkroom. In the lab, she started to learn techniques essential to her work today, but she never got to put her artistic talents to work. Instead, deCarvalho launched a scientific career, fulfilling her grandfather’s prophecy and eventually landing at UMBC in 2016.

Once she arrived at UMBC, art finally returned to her life. “Suddenly I realized I could do it,” deCarvalho says. “I’d say it was about 20 years later. I came full circle.”

Creating art, informing scientific research

The process of creating an artistic microscope image begins the exact same way as creating a research image. It’s only the post-processing that differs, deCarvalho explains.

“I take things further than what might be considered ethical for a research image, where there are clear guidelines as to what you can do,” she says. In a research image, “You can’t manipulate the image to alter any of the content.” For her art, she removes distracting elements like debris around the main specimen, and emphasizes the specimen’s key elements in a way that makes it more visually engaging.

Her modifications “allow you to focus your attention on [the specimen] more, and to find it more aesthetically pleasing,” explains deCarvalho. She believes this makes viewers “more interested in the content than you would be if I hadn’t slightly altered it,” she says. “I think it makes it more compelling.”

Her artistic work can still inform scientific image production. “I push the limits of my expertise by doing these art images,” deCarvalho says. “I can bring some of the experience and new techniques that I learn in doing that back to the research. It goes both ways.”

For example, for the winning tardigrade image, “I came up with that staining just to create that pretty picture, and I’ve had tardigrade experts all across the world and people that use tardigrades in classrooms ask me for my technique, because they could see structures stained that they weren’t able to see before with the traditional staining techniques,” deCarvalho says. “So it informed research, just from me trying to make a nice picture.”

Public art, amplified

One of the images selected for “Life Magnified” features moss that deCarvalho scraped off the exterior of the UMBC Biological Sciences Building. “I feel like it’s kind of an homage to UMBC that one of the samples was taken right off the building,” she says.

When asked about her motivations for turning microscope images into beautiful works of art, her answer was simple. “It’s super cheesy, but I just get so excited when I see things under the microscope,” she says. “I look through the microscope, and I just think, ‘Wow, I can’t believe that’s real, and that it just looks so amazing.’” Her art, she says, is “a way to capture the excitement and share it with other people.”

In addition to the connections to UMBC and to her grandfather, having her work on stamps is special because it grants her images the ultimate visibility, she explains. Stamps “are like a public art museum,” deCarvalho says. “Each one is like a little piece of art—it’s the most public art form. So when USPS approached me, I thought, ‘This is the highest honor.’”