“The term ‘medieval’ is used to mean something bad and backward—a period where travel was mostly viewed through the exploits of male merchants, pirates, sailors, soldiers, and clergy, not a period to help us gain insight into restrictive laws and gender roles,” explains UMBC’s Susan McDonough, associate professor of history. She’s just earned a 2019-20 National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to further research that is more inclusive of women’s experiences in the medieval Mediterranean.

“I want to look into the lives of medieval prostitutes to help us understand the gendered and political influences that fostered their roles as businesswomen and community members,” says McDonough.

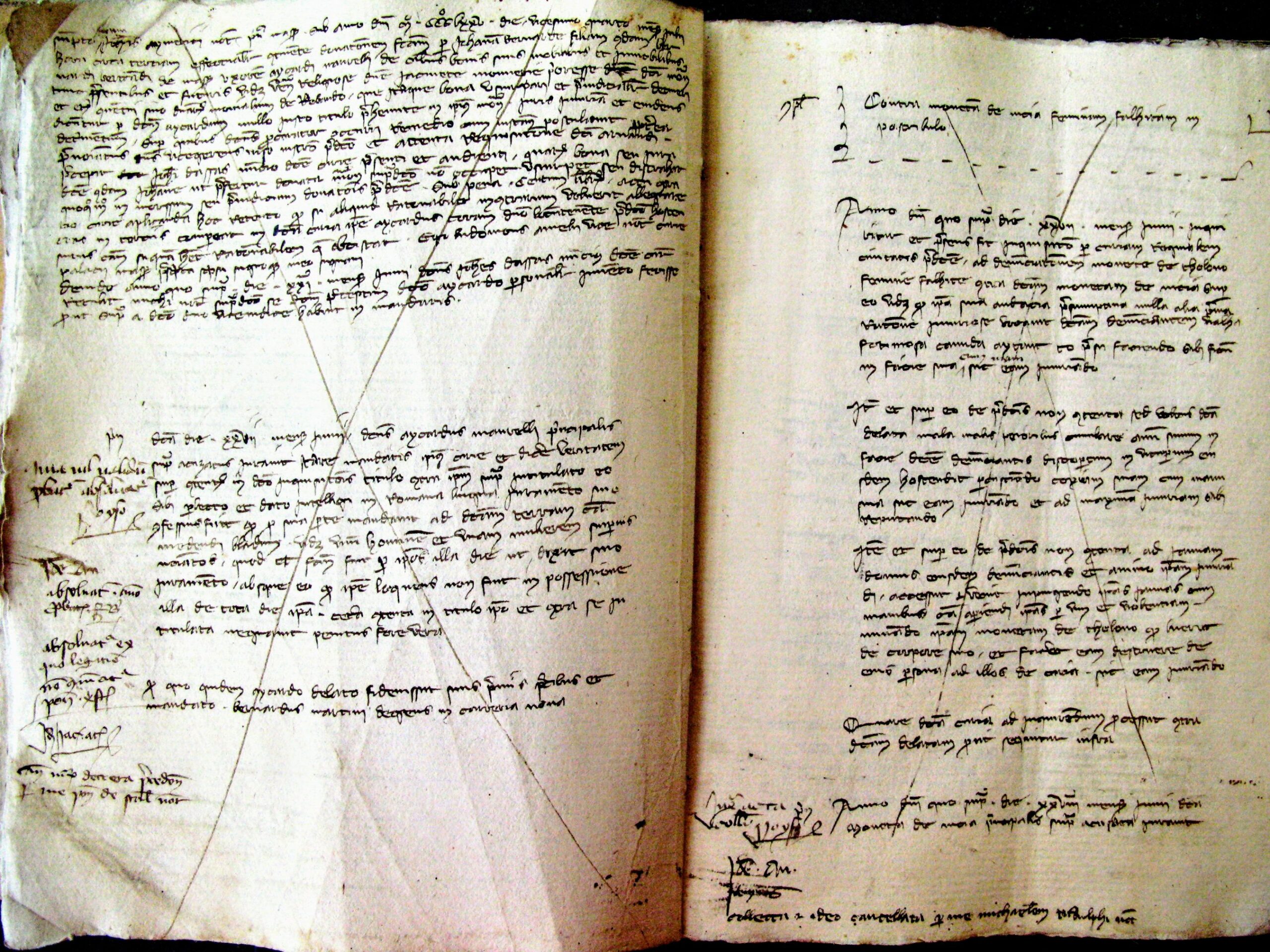

McDonough initially learned about the important role of female prostitution, a legal practice in the medieval Mediterranean, while researching her first book about witness testimony and civil court records in late medieval Marseille, France. “There aren’t many criminal court records that are still left from that period,” she notes. “I have one court record from 1380 and almost twenty percent of the cases deal with prostitution.”

McDonough explains, “Prostitutes are not twenty percent of the criminals or of the population, yet they’re overrepresented.” This fact piqued her curiosity about the benefits prostitutes might have gained by using the court system.

Defying municipal statutes

As she continued to investigate, McDonough found that prostitutes were going to court not because men had accused them of stealing or “respectable” women charged them with wrongdoing, but because of accusations and slander by other prostitutes. Beyond protecting their reputation, it seems they were using the court system as a way to access barred spaces.

“In Marseille, the criminal courts are outside and are next to an important church,” describes McDonough. “The statues for the city of Marseille say that prostitutes aren’t allowed to be in the spaces near churches. By going to criminal courts they are defying municipal statutes.”

Understanding migration

Beyond the deliberate choice of using the court system to maneuver around restrictive laws, there is also a question of migration. McDonough noted that despite the fact that most prostitutes were working in port cities around the Mediterranean Sea, they were not locals but had migrated from other places.

“The notion of migration inspired more questions about the reasons these women move. Is it out of choice or because they don’t have strong family ties? Are they going to port cities because they feel there is an economic benefit to being in a port city?,” asks McDonough. “I want to know more about what it means to travel in a body that is gendered female in the middle Mediterranean.”

Connecting the medieval Mediterranean to the classroom

The fellowship will give McDonough an opportunity to complete a year of archival research in Barcelona, Marseille, and other Mediterranean port cities, which will be the foundation for a book.

McDonough is also equally excited about bringing the research back to the classroom. “It is hard for me to leave for a year because I love teaching,” she says. “But this story will resonate with students because of how it informs us about how reputation and stereotypes affect the way people move through society and bear challenges and burdens because of them.”

Banner Image: Archive Latin manuscript about a case of a prostitute named Moneta de Nicia, from Archives Départementales du Bouches-du-Rhône 3B96 fol. 32r. Photo by Susan McDonough.

Tags: CAHSS, History, International Stories